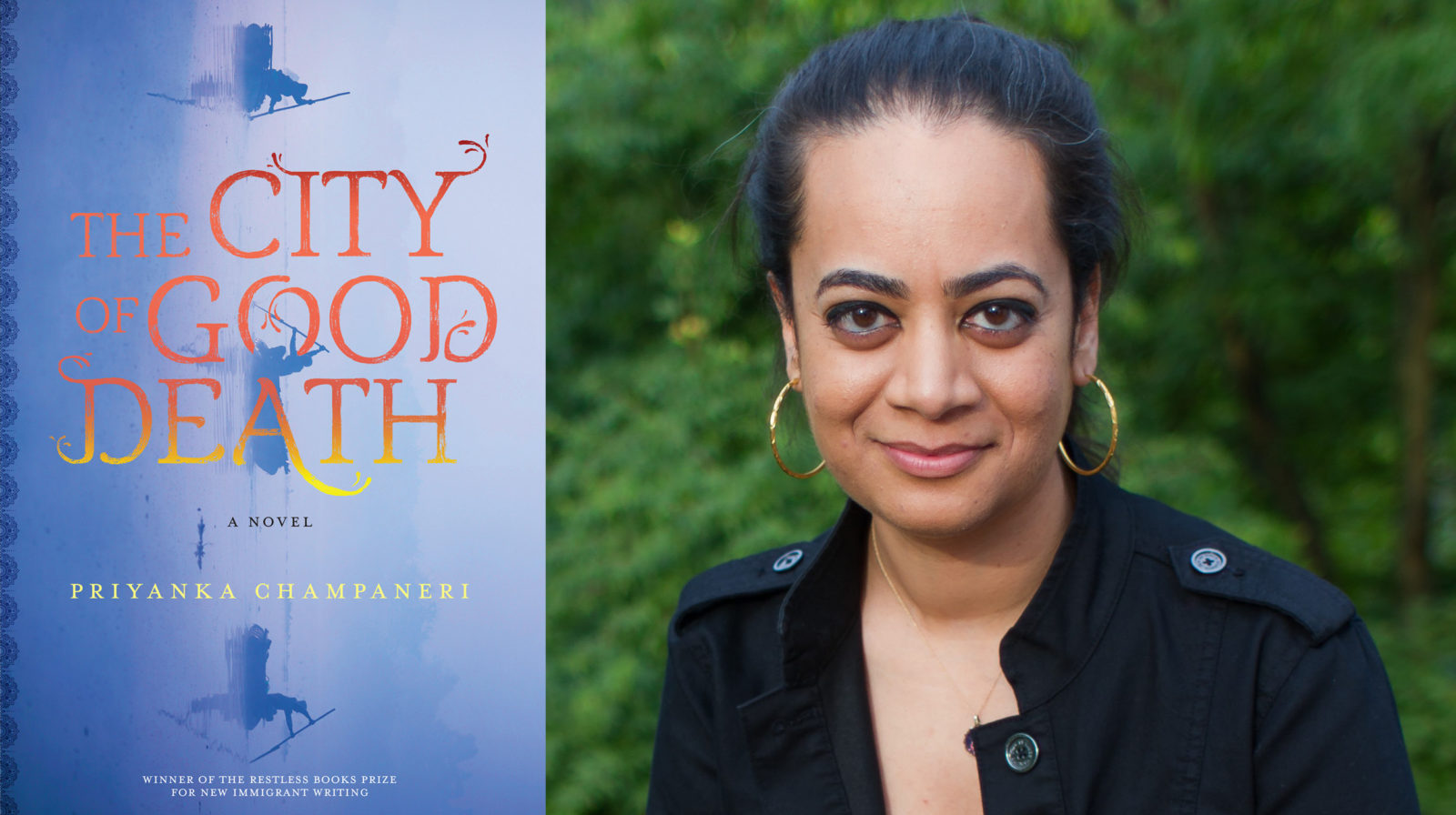

Celeste Kaufman, Manager of Marketing and Communications, interviewed Priyanka Champaneri, author of The City of Good Death, in celebration of being shortlisted for the 2021 First Novel Prize. The City of Good Death takes place in Banaras, a holy city in India where people will be released from the cycle of reincarnation if they die there. It centers on Pramesh, who began a new life as the manager of a death hostel in Banaras, and has been living contentedly until the body of his estranged cousin is found, the death rituals for him go awry, and the guests of the hostel mysteriously stop dying, forcing Pramesh to confront his own ideas about death, rebirth, and redemption.

What was the first kernel of the idea for this book? What couldn’t you stop thinking about that led to creating this story?

In between college and graduate school, I had a friend send me a Reuters article titled “Check in and Die, or Get Out” which was about the death hostels of Banaras. I was born and raised within a Hindu household, so it was a culture I’m very familiar with, and I knew about Banaras but hadn’t given it too much thought. Reading that article was my introduction to the death hostels, though, which I had not known anything about. For folks who aren’t familiar, these are places where, if you don’t live in Banaras and you’re in a certain economic status where you can’t afford anything else, you can bring an elderly family member where it looks like it’s probably going to be their time to go pretty soon and stay with them until the end. They’re very bare bones structures that have little to no amenities, but they offer that family and that dying person shelter so they can complete the process in this city. It’s a tremendous thing in a lot of ways, and I was just fascinated reading about this place.

In hindsight, I think that fascination hooks into two disparate parts of my identity. The first is the one that’s very familiar with Hindu culture and who has been trying to live this life within that spiritual philosophy. When I looked at the death hostel from that point of view, there was nothing out of the ordinary about it at all; it was a utilitarian place that was necessary, just like a rest stop along the highway. But I was born and raised in the United States and educated entirely within a Western education system. so I’m equally familiar with that perspective, and I understand how from that point of view a place like a death hostel might be viewed by folks accustomed to a different way of approaching things. It just seemed like an idea so ripe with possibility. I couldn’t stop thinking about the idea of the hostel, of the city, of everything that it promised.

What were your biggest challenges with writing this book?

This book was really unusual for me as a fiction writer. It was the first thing that I published, but I had been writing fiction before, and with all of the fiction I’d written before, usually I would start with a situation, or a conflict would pop into my head and character would come after, and setting was often very secondary. It was sometimes an afterthought, sometimes not really anything to be mentioned or delved into at all. This book was different because it started off with setting. I had this fantastic place, this city with so much meaning, and then the death hostel itself. There was so much to work with. But I didn’t have a conflict or a situation in mind.

On top of that, I’m also a very organic writer. I can’t write using an outline, I can’t write with a plan, I can’t write knowing what’s going to happen next because to me the joy and the fun of writing comes from constant discovery, from the page telling me what’s going to happen next, from the characters telling me what’s going to happen next. So that was the most challenging part, that I had this incredible world to work within and to play around with and walk around within the imaginary hallways of my brain, but I had to do the very slow painstaking process of discovering what that story was. That’s part of why writing this book took as long as it did, which was about 7 or 8 years. There would be weeks at a time where I was stuck with the main plot and I just couldn’t write because I was waiting to find out what would happen next and it just wouldn’t reveal itself to me. There would be weeks, months, there was even an entire year at one point where I just couldn’t move forward with the plot because the solutions weren’t coming to me. So, it was a matter of being really patient with the book, and just listening to the book, listening to the characters, and trying to really utilize that writer’s intuition of which way should I go, which story should I pursue, which character should I be listening to right now?

Now knowing that you worked on this very organically, I’m even more interested in hearing what your writing practice was like, especially during that year when you were so stuck with the plot?

The first year I was working on this book it was my last year of graduate school and I had a fully-funded fellowship, so I had nothing to do that year but work on this book, which was really nice because it gave me a good foothold. Then, when I graduated I went straight into full-time work and I could only write in the evenings and on weekends, and that first year was the one that I mentioned where I didn’t work on the book. I had to get accustomed to not being in that creative cocoon that an MFA program often is, and figure out my new reality of how I could make a creative life happen for me alongside my professional life. And then of course I think the story just needed that time to percolate in my mind. Once that happened, I became someone who primarily writes in evenings and on weekends. I tried to do the morning thing because it sounds so appealing to get your writing done and then have the rest of the day to enjoy your accomplishments, but I can’t do it. I’m a night owl; I really thrive when the whole house is quiet, it’s dark outside, it feels like nobody and nothing exists except for me and this story. I think that provides the perfect access point to slip into the world of the story and out of my current existence and reality. When I’m able to do that, that’s when the writing flows most easily and most organically.

What are some larger conversations or topics that your book speaks to or engages with?

I think the one that was probably most intentional on my part is this idea of memory, how memory plays a part in the story that we tell ourselves about ourselves and our life. Everybody has this internal story that they’ve built up out of memory, and they tell themselves this story constantly, and the more you recall certain memories in the way that you remember them, the more you are essentially reaffirming them that way in your brain. Yet what fascinates me is you can have somebody who was at the same event, at the same point of time, and they can recall it in an entirely different way, almost as if they existed in a different reality, and both of you can be right! I’m interested in the fallibility of memory and how intently we hold onto these stories we tell ourselves, and how traumatic it can be when you realize that something you had told yourself for decades is completely wrong, or at least that there exists a different perspective of it. Plus, all of the work that you have to do— the emotional, spiritual, psychological work— that you have to do in order to reconcile the two and essentially rewrite the story of your life for yourself, and sometimes people are unable to do it.

Since this is your debut as a novelist, what do you hope this book says about you as a writer? What can we expect more of from you in the future?

In terms of myself as a writer, my ultimate goal is when somebody reads this book they become so swallowed in this story that my presence is absolutely annihilated. I think I will be successful if all that exists is the reader and the story and there’s no barrier of my presence in between them and the story. Those are the types of books that I enjoy the most, where it feels like I get to be a character in the book because I’m observing it and there’s nobody else between me and the story. In terms of future work, it’s hard for me to answer that question because I’m intensely superstitious, so I never talk about what I’m working on. With this book, for 5 or 6 of those years that I wrote it, nobody knew that I was working on anything. I didn’t tell anybody about it at all. But I’ll also be honest with folks out there, this specific year, 2021, I haven’t written anything at all. Sometimes it’s just not going to happen. My own personal goal is to just always concentrate on the present. Just because I wrote one book, it’s not guaranteed that I will be able to write another one. I would love to, I would really really love to, but I count myself very fortunate that I got to write this book, and even luckier that I got to publish this book, and then to be nominated for this award, it just surpasses any sort of reality I could’ve pictured for this book. So I’m really grateful for what I have gotten to do with this book and I certainly hope to do more, but I never expect it.

The description for this book says that it’s a story about a death hostel that’s been disrupted by an “unwelcomed guest” that’s never explicitly stated as the spirit of the cousin whose death opens the book. Would you consider this to be a ghost story, or is that classification too centered around an American concept of death (or of ghosts, for that matter)?

That’s a fabulous question. I think certainly because there is a ghost or the presence of the supernatural in this book, in that sense it could be classified as a ghost story. But for me, when I think about a ghost story, that supernatural presence is really the center of the book and I don’t necessarily think of this book in that way. I grew up reading fairy tales, absolutely inhaled them, and I still love them to this day, especially ones from the eastern part of the globe— Indian, Chinese, Japanese, Korean etc.— and the one constant in a lot of those stories is this easy coexistence between the spectacular and the everyday. You can have this supernatural element that’s existing around these characters in their everyday lives, and these characters aren’t necessarily shocked by the presence of such a thing. Its presence is speaking to some other conflict that needs to be solved. I really wanted to try and do that with this book, to show that there is space out there for a type of culture where not everything is explained and that’s okay, and it can still exist along everyday life.

I think a lot of that comes out of my own desperate wish for the possibility of, for lack of a better word, magic in everyday life. We live in this world that’s so technologically advanced, every day in the news some mystery that has mystified human civilization for millennia is being solved. In my lifetime, we went from not knowing how the dinosaurs were wiped out to now we know how and when they were wiped out. Of course that’s incredible, but it also makes me a bit sad because, the more we solve the answers to things, the more we diminish the possibility for mystery and for magic and for the unexplainable, and I’m always looking for a chance to observe something in real life that we can’t explain. I think it comes from me being a little girl and being in my backyard and being so desperate for a unicorn to walk into my backyard; I wanted something incredible to happen like that.

And now you get to create something magical! That’s beautiful. For a story so centered on place, I read that you’ve never been to Banaras. The world-building of this city is so vivid and felt so lived in. How did you prepare for writing about a place that you didn’t know?

It’s really kind how you phrased that question, “how you prepared,” because it makes it seem like it was really intentional and it wasn’t at all. I mentioned at the top of this conversation just being captivated by this article that my friend sent me and being sent down this rabbit hole that I now know was research, but at the time was just this fun side learning project that I had. So, I was just reading all of the books I could find on Banaras and the death hostels. I was clipping out articles from magazines and newspapers, watching documentaries and movies, finding these out-of-print books of photography of Banaras on eBay and really putting myself into the world. What ended up happening is after years of this process, I ended up building this imaginary version of this city in my head, and it was vivid enough and real enough that I started seeing characters walking through that city, I started hearing snippets of dialogue, I started seeing things happening, and it was really that part of the process, with these sparks going off seemingly out of nowhere, that prompted me to think maybe I should sit down and see if this could be something.

Throughout I had been very trepidatious about starting anything. That’s one of the reasons it took so long between reading that article and actually starting writing this book. I hesitated quite a bit because I’m not from Banaras; my parents are from Gujarat; which is in an entirely different state from Uttar Pradesh, where Banaras is. I was born in America. I’m not familiar with the predominant languages that are spoken in Banaras because I am Gujarati and our language is Gujarati. It felt like there were a lot of tick marks against me and I did not take it lightly. I very much feared being seen as an outsider coming in and taking ownership, very strange ownership, over a city that is very important and iconic to a very large population of people.

In the end, one of the reasons I decided to move forward with it were those sparks that came, because with inspiration, you can’t control when or how it’s going to come. I suppose some folks might’ve been able to pass up that temptation but I could not. The other thing is, I realized in hindsight how much I did bring to the table that I didn’t think about before. While I have not been to Banaras I have been to India twice, only as a tourist, and from all those experiences I had just soaked up everything that I saw, that I smelled, that I touched, that I heard, and just stored it away in this storehouse of this memory that I have because they were all interesting details to me. Not to stereotype an entire country that is huge, but there are so many things about India that can be universal, like interactions with neighbors, interactions in a marketplace, how certain things are set up. Plus, I did grow up in a Hindu household and it is a spiritual philosophy that I have tried to practice in my day-to-day life. So, it was really a balancing act between what I did not know, what did I not have firsthand experiences with, and how I could fill in those holes and supplement them with research.

Do you have plans to visit Banaras now, or is it a place where you kind of only want it to exist in your head?

It’s a really interesting question, because I think part of me, from a spiritual point of view, feels like it would be really good to go and to know it firsthand. Part of me is terrified of going because if and when I go I’ll see everything that I got wrong. Part of me wonders if I should just let the Banaras in my head be the only version of the city that I know. Like any modern city, it is changing rapidly, so is the city that I read about and that I saw in photographs and in documentaries and that I wrote about, ultimately, does that city even exist anymore? And if it doesn’t exist, would I be able to handle the psychic differentiation between the one in my head and the one that I see in real life? So, I don’t know. I feel like if somebody offered me the chance to go, I’m somebody who tries to say yes to as many things as possible so I would probably go. But I would think long and hard about it, and I would be very anxious about it the whole time before actually seeing it.

Our entryway into this story is this mystery within the confines of the death hostel, with these supernatural elements and these grand spiritual questions. But the story quickly expands beyond the walls of the hostel to have this classic, almost Victorian feel to it with this sprawling cast of characters who are all circling around one another in this city and out in the country, and their primary conflicts and concerns are these matters of family and marriage and duty. What do you see as the relationship between these two aspects of the novel? How did you decide that you couldn’t answer these spiritual questions the characters are asking without also answering questions about these very earthly concerns, and vice versa?

I think at its core, the spiritual and the earthly are really inextricable. As long as we find ourselves living on this planet Earth in this current time, it’s impossible to separate the two. You can read as much as you want about any spiritual practice, but my question is at the end of the day does it really matter what you tell yourself you believe, or the philosophy that you tell yourself that you’re going to abide by, if you don’t apply it in your everyday life? That is fascinating to me, how people end up reconciling their spiritual philosophy, their spiritual practice, their beliefs, or their lack thereof, with their everyday life. Are they successful, or are they not? Are they hypocrites? It would be one thing if all of us just decided to go live on a mountain all by ourselves and meditate and that’s it, but that’s just not something that can happen in everyday life. So they have to intersect in some way.

From the point of view of writing fiction, it’s really hard to write a book where the conflict is entirely spiritual because that makes it an entirely interior conflict. How do you make that interesting for a reader to only be delving through a character’s mind? How do you keep a reader turning the pages if they’re only reading what’s going on in a character’s head? So having that outside, forcing that character to go out and interact with the world, and do that work of reconciling what they believe with their everyday life gives the reader more to dive into. I think that’s something I’m never going to be tired of exploring because that’s a question I ask about myself on a day-to-day basis. How do I make this thing that I believe, that I think I believe, or that I’m trying to convince myself that I believe, work with my day-to-day interactions with all the people around me?

Featured Book

-

.

The City of Good Death

By Priyanka Champaneri

Published by Restless Books

India’s holy city on the banks of the Ganges has many names but holds one ultimate promise for Hindus: it is the place where pilgrims come for a good death, to be released from the cycle of reincarnation by purifying fire. After ten years living contentedly as the manager of a death hostel in the city, Pramesh’s past reemerges in the form of his estranged cousin’s body being pulled from the river, triggering a series of events that forces him to confront his own ideas about death, rebirth, and redemption.

About Priyanka Champaneri

-

Priyanka Champaneri

Priyanka Champaneri

Priyanka Champaneri received her MFA in creative writing from George Mason University and has been a fellow at the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts numerous times. She received the 2018 Restless Books Prize for New Immigrant Writing for The City of Good Death, her first novel.

Photo Credit: Lauren Brennan