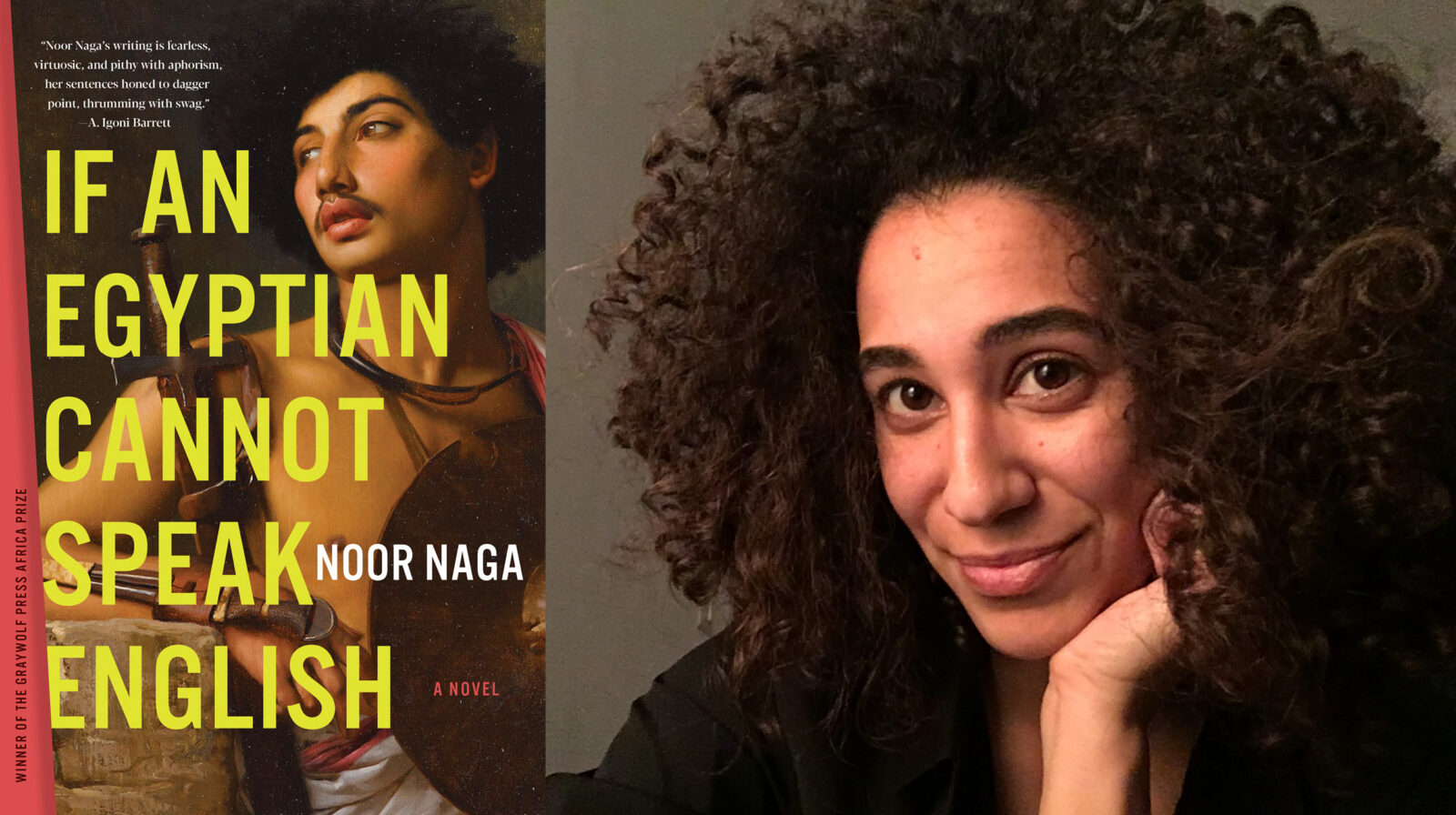

Noor Naga, author of If An Egyptian Cannot Speak English, spoke with Harry Cash, Bookseller at The Center for Fiction, in celebration of being shortlisted for the 2022 First Novel Prize. In the aftermath of the Arab Spring, an Egyptian American daughter of immigrants nostalgic for the country she’s never lived in falls in love with a man she meets in Cairo who was a photographer of the revolution, but is now addicted to cocaine and living in a shack. When their relationship takes a violent turn, the fallout exposes the gaps in American identity politics and reexamines the faces of empire.

What was the first seed of this book? I know that excerpts of it were published in Granta in 2019; what was the process like of developing that story into the novel-length form?

It started as most of my projects do, with the voices. I began with the voice of the boy from Shobrakheit and I didn’t really understand what it was that I was writing. I was just kind of following it along and trying to understand who this character is, and who would speak in this way. One exercise that I often do when I’m at the beginning of a project and trying to decide who is speaking and what is the thing that I’m circling around, is that I try to translate what I’m working on into a question. I’ll take paragraph by paragraph and section by section and think, “What am I asking here?” Normally I take those questions out, but I liked the interplay, and the relationship between question and answer, so I pushed them a bit further and made them a bit stranger, and decided to keep them.

So, that’s really how it began. This nagging question or preoccupation or obsession was just how untranslatable ethics are across borders. What it means to be a good person, or a privileged person, or a marginalized person, or a good ally even, all of these things look so different and are so context-dependent. I was really curious what happens when you try to export values from a North American space to the third world, and to what extent do they apply. The same thing goes for when you’re trying to move from rural areas to urban areas, even with Egypt, the value system in the provinces and the villages is very different from the capital and these other urban centers. I was really curious what would happen when two people from such dramatically different worlds come together. How do they see each other? How do they see the place that they’re in? How do they understand their positionality in this new context? What are the things they miss or get wrong?

Something I was really struck by was how much vulnerability and shame and hyper-awareness of difference comes up through shibboleths. The perspective changes really highlight these rifts that have to be overcome or are not overcome by characters in the book. Was that your intention with the perspective changes, exploring those rifts and friction points?

Those markers of difference and non-belonging are something that I’m hyperaware of because I’m such an outsider in all of the places I live, even in places where it’s assumed I’m on the inside. I’m constantly perplexed and confused by different rules of engagement in different spaces. I’m also always aware of who is being excluded at any one moment—who is on the edge of the circle, who is outside the circle in order for us to feel that we are inside of the circle— and how we perform belonging.

With the different shifts in perspective between these two characters, it was really just a way to show what each of them was missing. What are they not getting? I wanted each of these characters to be as intelligent as possible. I didn’t want the reader in the position of greater awareness or greater knowledge or greater intelligence. I wanted them to be extremely sophisticated people in very different ways and coming from different knowledge traditions, and try to show even then that there is a gap, that there are things that are misunderstood or just missed. But there is also this constant attempt at being in the same space, at togetherness. For contextual reasons or circumstantial reasons, though, that’s not completely possible.

I kept thinking about this quote from an anthropologist while I was reading, where you should treat it as axiomatic that every member of a social group is a competent user of the social system that they’re in. What were your biggest challenges when writing this book?

One of the more difficult ones was how to be fair to each of these characters. I wanted them to be complex, but I didn’t want the reader to be able to fall easily into either villainizing or making heroes out of them. I wanted to keep a balance of goodness and weakness in each of them. That balance was really hard. Because it’s such a sparse novel, even the tiniest changes sometimes tipped too dramatically one way or the other, and I wanted people to be unsure how they feel. The ending was also difficult for similar reasons. I wanted to implicate myself in the end and I wanted to bring some metafictionality into the piece and I wanted the reader to be suspicious. I wasn’t always sure to the extent some of the experiments towards the end were working, and I’m not sure to be completely honest how much it worked

I really liked section three.

Okay, that’s reassuring.

It felt like, for me as a reader, this break where you got to process everything, in a way. I really enjoyed being walked through these different reactions and watching this grappling with the story played out by these other characters in the writing workshop. It was really quite lovely, I thought.

I’m so glad!

What are some of the larger conversations that your book is engaging with? I felt that part three really brings to the fore a lot of concerns about putting values in certain contexts in an interesting way.

I was thinking a lot about the short story, “Cat Person,” and its whole unraveling as I was editing. If you’re not familiar, a couple of years after the story went viral, this woman came out with this article that said she was “Cat Person,” this writer basically stole her life. This writer didn’t know her, but she knew of her and she had written this story getting so many details of this girl’s life correctly that as soon as this story came out multiple people messaged her and said, “Oh my god, is this you?” And the same thing with the guy from the story. Eventually, he plunged into a depression and committed suicide. So, I was thinking a lot about the real-world implications of using real life for inspiration for literature and the ethics of that and the problematics of that, and thinking about who gets to tell what kinds of stories, and what are the repercussions for those who are represented in those stories. What opportunities did those characters have to represent themselves, in what mediums, in what language, and to what audiences?

I was also thinking about the whole MFA industry in the United States and creative writing pedagogy and what axioms are tossed around in these spaces. Like, “write what you know” and even things like “show don’t tell,” which assumes that your audience has the tools to recognize what they’re being shown. What happens when you present a narrative outside of its original context to an audience that doesn’t have those tools or that value system? What kind of violence is possible in those contexts?

You were mentioning that the book is almost ambivalent about these characters, that it’s meant to be ambiguous about who is in the right and who is in the wrong. What interested you about that?

I think maybe I’m reacting against literature that is didactic, which is sort of the trend right now, at least in North American literature in minority voices. The premise, the point seems to be, “Look at this awful thing that has happened to us, oh woe unto us.” You know, “Look at how we struggle, look at how we fight back.” I’m all for political literature, but I’m very suspicious of those kinds of narratives and I find them really boring, uninteresting. I often wonder what is the purpose of this, who is this book for? Is it for people who already agree with this kind of narrative? Is it actually evoking change in the world? I don’t really know. I’m much more interested in literature that is balanced on the edge and that is asking questions. The writing that I love most leaves me with more questions. I’m a huge fan of J. M Coetzee. He does this incredibly well. He constructs these elaborate philosophical problems and you can hate certain characters, and you end up hating most of his characters, but there’s such sympathy for all of them. I find that really vibrates in the same way that I do.

This was one of the more formally inventive books I’ve read. I was wondering if there were decisions in creating the structure of the book that were provided by that thematic concern?

I had been initially trying to write two true voices, and trying to get at some kind of middle-ground truth. I showed the manuscript to a good friend of mine who is Egyptian and he immediately said, “Well of course you don’t actually have two voices, you have one voice. You’ll never get it right, you’ll never get the boy’s voice right. You can sort of lean into the girl, you’re close enough, but you’re too far from this guy and you’ll never get it right.” It was a tough call but I realized he was speaking to something, and so I decided to push that wrongness as far as I could and make it a part of the novel. I don’t know if that was so much a function of ambivalence as it was a function of my own awareness of the limitations of my imagination and the limitations of cultural appropriation generally, even within the same culture. What does it mean to step outside of your experience, how far can you actually step, what does that step look like? I think that a lot of this book was coming to terms with how far I can personally step or how far I wanted to step. I could’ve done more research, I could’ve gone to Shobrakheit, I could’ve spent more time with people there. But I felt the project would be doomed from the beginning in some way if I did.

To go back to part three, I thought involving yourself in that metafictional way was so interesting, because your character is present in that scene and is talked about as a writer, but you’re also completely erased from that section because that character doesn’t speak. Then the rest of the characters in the workshop, there was something so true and deeply American about these participants talking over each other and against each other about the book. How did you go about drawing those parallel collections to the misapprehensions that took place in the first and second parts of the book that get repeated in this third part?

I think that many of the members of the workshop are probably closer to where the girl was before she goes to Cairo. She arrives in Cairo with this kind of rhetoric in her mind, but I do think that she returns changed and is struggling to articulate what this change in ideology means. She’s not allowed to speak—this is a common practice in workshops and one that I spent a lot of time thinking about, this gag rule, and how useful it is to have the author of the piece sitting silently while others are interpreting or misinterpreting their work. I understand where it comes from because when you don’t have a gag rule, authors tend to step in and do the interpretation for people and get defensive. So, I get the spirit behind it but, in this case, I felt that the silence was not so much forced upon her as much as it was also a reflection of her own alienation.

Even in the short text that she reads from the missing part three, that is some evidence of how she feels in that moment, and you’re right in that everyone is competing to get it wrong. It was difficult because I wanted it to be obviously satirical. I wanted the reader to feel a strong disconnect from what they were hearing in this room. I wanted anybody who arrived in this room to feel like, “Wait a second, you guys are missing something,” and to be sort of irritated or uncomfortable or angry. I also didn’t want to tip into too much of a satire so that the characters become caricatures and it’s just sort of a parody of identity politics, because I understand where these characters are coming from and a lot of them are coming from spaces of personal trauma and frustration. So, they’re also not wrong, they’re just sort of missing something. They’re also caring for their friend. This is the person that’s in the room with them. They don’t know this guy, they read about him but they have a living breathing person in front of them who they’ve presumably been meeting up with for this whole semester and she’s saying this is something real that happened to her, and she’s obviously affected, and so it’s also a form of care, a form of tenderness, even if it’s misguided.

Since this book is your debut novel, what do you hope it says about you as a writer? What can we expect from you in the future?

I hope that readers will leave my book very suspicious of me, but I hope not turned off. I hope to always bring some sort of formal experimentation and levels of metafiction and self-awareness to my projects, so I hope that this is the direction I’ll be heading in, but I also don’t know. I’m writing something very different right now; there’s no metafiction at all, there’s no plot twist, so hopefully, readers won’t give up on me. This is what I’m hoping for.

Well, I really enjoyed the book. I’ve been on this weird kick of mid to late twentieth-century Latin American writing and there was a kinship that I felt in some of the formal choices, which I really enjoyed.

I’ve heard that from more than one person, actually. I definitely stole having a character named after myself from a bunch of different Latin American authors who seem very comfortable with it and who don’t find anything problematic about it. Like César Aira is always in there.

Roberto Bolaño is always Arturo.

Yup, he’s always in there, hanging out. I find that really fun and I don’t know many women who do it.

Featured Book

-

.

If an Egyptian Cannot Speak English

By Noor Naga

Published by Graywolf Press

In the aftermath of the Arab Spring, an Egyptian American woman and a man from the village of Shobrakheit meet at a café in Cairo. He was a photographer of the revolution, but now finds himself unemployed and addicted to cocaine, living in a rooftop shack. She is a nostalgic daughter of immigrants “returning” to a country she’s never been to before, teaching English and living in a light-filled flat with balconies on all sides. They fall in love and he moves in. But soon their desire—for one another, for the selves they want to become through the other—takes a violent turn that neither of them expected.

A dark romance exposing the gaps in American identity politics, especially when exported overseas, If an Egyptian Cannot Speak English is at once ravishing and wry, scathing and tender. Told in alternating perspectives, Noor Naga’s experimental debut examines the ethics of fetishizing the homeland and punishing the beloved . . . and vice versa. In our globalized twenty-first-century world, what are the new faces (and races) of empire? When the revolution fails, how long can someone survive the disappointment? Who suffers and, more crucially, who gets to tell about it?

About Noor Naga

-

![Noor Naga[47]](https://centerforfiction.org/uploads/Noor-Naga47-scaled-1600x1200.jpg)

Noor Naga

Noor Naga

Noor Naga is an Alexandrian writer who was born in Philadelphia, raised in Dubai, studied in Toronto, and now lives in Cairo. Apart from her debut novel If an Egyptian Cannot Speak English, she is also the author of the verse-novel Washes, Prays. Noor teaches at the American University in Cairo.