December 3, 2023

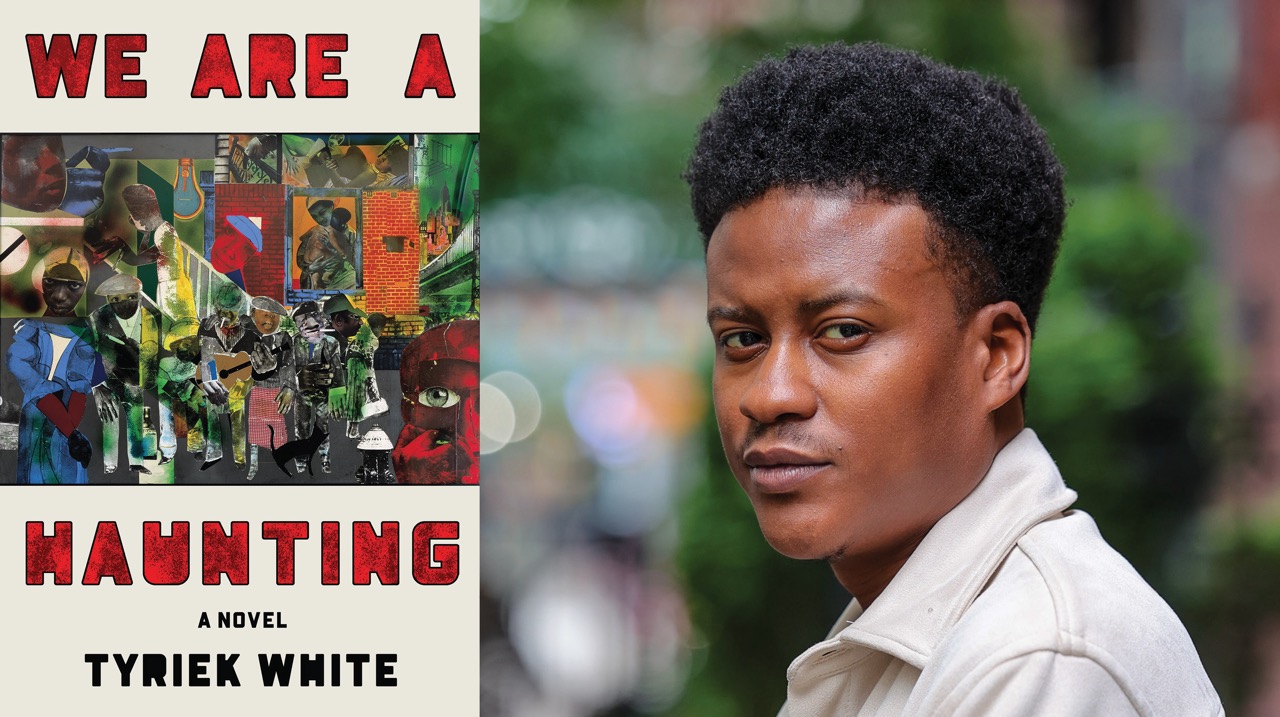

Tyriek White, author of We Are a Haunting, spoke with Celeste Kaufman in celebration of being shortlisted for the 2023 First Novel Prize. In the novel, Colly discovers he has inherited his mother’s gift of being able to communicate with the spirit world, and begins to slip into the liminal space between the living and the dead on his journey to self-actualization. The intergenerational family story shifts between the East New York of present-day and the 1980s, interrogating how to build a collective path forward from the wreckage of the past.

What was the first seed of the idea for this book? What couldn’t you stop thinking about that led to creating this story?

I think the story has lived with me for a while. I always wanted to write about growing up in Brooklyn, growing up in East New York. I didn’t necessarily know how that would look, but I always wanted to write toward the idiosyncrasies of growing up in a place that, even spatially, is mapped in a way that raises questions. I grew up on Schenck Avenue, and I was always curious about things like, “Who was Schenck?” Those kinds of simple questions, wanting to know the history of this land, this community, and the ways in which those tie together with the contemporary. That came with different voices, different characters coming into the story, and I was just riding with the ebb and flow of that.

What were your biggest challenges with writing this book?

One was being away from the place I was writing about, but that also turned into a benefit because I was able to write about it in a way that was new and different. Also, the responsibility of holding these stories, and deciding which stories to tell, and which stories were mine to tell. The whole book is this meta conversation with myself about ownership over narrative. You’re growing up in this place and you see people, you see families, you see your friends going through things, and there’s that weight of not wanting to say too much. Even though this is fiction, it is people’s lives to an extent. There are moments in this story that outwardly refuse to give certain information. There are false starts. There are stories that end in a way that doesn’t necessarily follow through to the full ending of the story, but this is where I choose to end it. This is where this character chooses to end it. I think there’s a lot of autonomy in that—these refusals of giving this space, this literary space, this mainstream kind of world, all of our secrets, all of our traumas, all of our pain that we harbor.

Could you expand a little on what it was like writing about such a specific place, and a story that’s so centered on place, from afar and what you said about how that ended up helping in some ways?

The con was not directly having that place as a resource, and you would think that takes away from the immersiveness of it, but this is the place I carry with me. I carry Brooklyn with me wherever I go. We all carry the places that we’re from with us. It wasn’t even a concern while I wrote, it was moreso capturing the rhythm of that place. Being afar changed that rhythm. There are places in the story where you get the busyness, the pace of being in a city, and then there are places where the story slows down and it feels like you’re transported to where I’m at, the South, Mississippi. The slower pace here allowed me to focus on different aspects of that place that I normally would.

For instance, thinking about land, thinking about the natural environment that you don’t normally think about, especially in the more urban parts of New York. My neighborhood is public housing, it’s factories and warehouses, there’s an industrial park a few miles up. So, geographically, you would think of it as brick, stone, asphalt. But it’s also near an estuary, it’s near the coast, it’s near a bay. So, there are plenty of opportunities to write into that natural environment. That was my favorite part, looking up what kind of plants grow in East New York, looking up the way marshlands work, or looking into the history of East New York and finding that those marshes were a swampland, and learning how these natural elements mixed in with the history of this place. I say this a lot, but the mob used to bury bodies in this neighborhood. And the community was on top of a landfill for years and years until they took it out in the eighties. So, thinking about place in this way helped me write something that I hope upended people’s image of miles and miles of brick and stone and concrete.

Was there anything that drastically changed about the story over the course of writing the first draft through publication?

I think for me it was my commitment to the supernatural, the magical realist element. Before, I was going to play more coy with those elements and have it be this figment of Colly’s imagination. Is Key, his mother, going through some sort of mental break and these things are representative of structural failures? But, I decided to lean into it, just go full on ghost. There’s a version of the story that exists as if this was all a figment of their imagination, and is kind of leaving it up to the reader to decide. But, I think with having those things there the reader makes a choice anyway—they can follow this thing fully and without inhibition, or they can choose that these people are maybe a little crazy. I’d never read anything about poor families living in public housing be wrapped in this magical realist plot. More and more, I wanted to read this thing. I wanted to see this slip into the genre in terms of reading about working class people, reading about black and brown folks. It was exciting.

Well, that perfectly queues up my next question. I always love a story that has ghosts in it as opposed to “a ghost story” in the horror sense. What are your thoughts on the role ghosts can play in literature? What role do they play in this narrative specifically?

Throughout literature and storytelling, ghosts are perfect for a character confronting their past, or confronting history. I think my story leans into this confrontation with history where the ghosts become embodiments of these moments and these eras. Also, that sense of retreat. Colly is experiencing loss and grief. His mom passed away from cancer, and he keeps seeing her ghost, hearing her voice, and I think in that loss and that grief there’s a chance for retrieval, for seeking out and finding this person again in a different way. He learns about his mom in her absence, from a different lens, and he begins to put together his mother’s more complicated than he thought. That retrieval is very important because it becomes the basis of his new relationship with her when he accepts that she will always be with him in that way.

Colly and his grandmother, they see only one ghost, whereas Key has this power where she is overwhelmed by all these things and it kind of places her in different points in time. It was a way to show parallels back during her mother’s time, and then further back during slavery, and how that institutional state violence mirrors the contemporary state violence, whether it concerns the police or addiction, fear of losing their job, the healthcare industry. With all of these things I’m using the ghosts to show the cyclical nature of how systemic injustice occurs, how even though we want better for our kids these things still manifest.

I love a good ghost story too, but I love especially when it services our relationship with the past. I think Western ideology is one foot in front of the other, forward movement always, but if you look at central principles in other cultures—West Africa, Sankofa—the only way to go through is to go back, the only way to retrieve a thing is to go back. So, I hope this expands people’s relationship to the past, their relationships to loss, and the shit that haunts them. You don’t have to run away from these things. Sometimes it’s best to confront them.

Do you consider writing about place to be a political act? There was something about the specificity of how you wrote about place, the naming of things—New Lots, Linden Boulevard, Van Siclen—that felt very special to read, even as someone who lives adjacent to these places and didn’t grow up there, because I was conscious of how unusual it was to see these particular references in a novel. Was it your intention to create that kind of representation for this part of Brooklyn in literature, or was it more something that was inherent to the story you wanted to tell regardless?

It’s an interesting question, because this story could be about any place where working class people, immigrants, any sort of community that’s disenfranchised live. We all have these connections to place, we all have these connections to community. I really loved where I grew up, and maybe that’s just the rose colored glasses of nostalgia. There’s guilt and shame in growing up in these places because of its connection with poverty, because of what it signifies, and I never really felt that. I think this book, even though it’s entrenched in what it’s like to survive day-to-day when you’re confronted with these structural inequalities, is an answer to the pathological thinking that goes into when you grow up in a place that’s poor or working class. To write this magical place, this community that has this magical element, felt good to me.

I contemplated situating this in an imagined neighborhood, but I felt that the kind of archive I was building, the music, the energy, the kind of richness of the culture in a place like this, worked better when there was a tension behind it. I tried to make it as three-dimensional as I could, and I think being unflinching in portraying this place, and being able to locate this place, being able to say, “I know that stop, I know that park,” allowed me to tap into the actual history of a place. When I read about the burial grounds on New Lots, it was one of those things where the research and the archiving made me realize I have to put a face to this and be specific.

At first, on a very superficial level, I was worried about folks from other cities or towns maybe not being able to tap into that same familiarization, but I know the specificity is universal. Maybe people don’t know this block, but they know the feeling of fearing losing their job, they know the feeling of not being taken care of the way they should in the hospital, they know about facing potential eviction. They relate to these very human things. They relate to a kid losing his mom. I think people responded to the living breathing characters of this community, even though they’ve never been to this place.

I was surprised at the section that revolved around MoMA, and the role visual art played in the storytelling through that part. Could you talk a little about how you felt art—as a concept, as an industry, as a medium—interplayed with everything you were exploring throughout the rest of the book?

I decided very early on that this was going to be an artsy book. I’ve had people say to me, “How would these characters, from these sorts of places, with these kinds of backgrounds, know this information? How would they know this poem?” You think working class and poor people don’t engage with art on a high level? So I knew I wanted to deal with art, especially from the perspective of a young person going through grief, or a young adult coming into their own and finding their place in the world. For me personally, I know how important that was for me and how I found myself. I wouldn’t have made it without music. I wouldn’t have made it without writing. Art changes you and expands you as a person, it does. It’s vital.

On a craft level, I made playlists for each of these characters. I thought about what kind of art would this person like, what would this character read? I was thinking of music as the journey of America. Music generating time. How it characterizes the eras, the time periods. So for Colly, I thought of him being of this hip hop tradition, and his mom being of this R&B, early hip hop tradition, and his grandmother being of this soul, R&B, jazz tradition, carrying this throughline of Black music. But, also having it encounter other forms of art during these periods. The conversation he has about John Cage and J Dilla in the museum—and this is the only sort of situation where these two things can be in conversation with each other— and seeing what that looks like, and privileging J Dilla and John Cage’s influence on the same page. Having those conversations and making those connections was why I wanted to have art play such a role in it.

Another thing that felt particularly unique about the representation of New York in this novel was— I was realizing how unusual it was to be reminded that New York City is an island in the many, many, many depictions we’ve seen of it. Every time the characters were casually referencing the shore or the harbor or the bay or the marshlands, I was thinking about how these things don’t get mentioned as often because the people who live their lives around this epicenter of the city so rarely, if ever, venture anywhere beyond that, and there are huge swaths of this city a lot of people have never bothered to see. It got me thinking about how only the people on the outskirts of this city have this relationship to the waters surrounding it. And you draw attention to water in other ways too — Igbo Landing, the Oyster Woman — so, what are the roles you were intending water to play throughout?

There’s a long tradition of water in literary works, especially folk and the African American diaspora. There’s water present in a lot of communities of folks who migrated here— water has always been this kind of transitory space. So, I think for me the presence of water came into focus with Igbo Landing, and this image I had of what if Igbo Landing happened in Brooklyn? It came to me before I even started writing. I just had this image of Black folk lined up on the shore, and I was figuring out how to make it make sense. It started for me as the kind of folklore and myth that surrounded this actual historical happening, and this image I had in my head, and throughout the story making connections back to that. And then realizing that this is a community that’s surrounded by water. The chance or the opportunity to make it this entity, to have it represent life but also have it represent a burial ground.

I read about how Africans who were kidnapped and brought here formed relationships that they wouldn’t necessarily have, because of the language barrier, because of this traumatic experience. A lot of them had this version of Igbo Landing, this kind of— I don’t want to say mass suicide— but this belief in taking autonomy over your life and your death as a fuck you to these captors. The thing about that as a form of resistance is it shows your ideology isn’t rooted in these Western ideals of death being the end, or death having this finality. Cultures where life and death are cyclical made me think about what death and community death means. So I was curious about all the ways that water offers access to death, to life, to land, to the entire world, to entirely new worlds.

I saved my most serious and most hard-hitting question for last. Have you ever encountered a ghost?

Yes, I’ve encountered ghosts many times. I’ll tell you two stories. I was upstate at poor kid camp. It was fun, but it kept feeding into how the place is haunted. Well, I looked in the mirror one night and there was this face behind me. I screamed, never forgot it. More seriously though, I was at one of my closest friend’s house after his little brother was killed in the worst possible way, and we were packing up because housing had granted them an emergency transfer. While we were in his brother’s room, the door would just slam any time we made to leave. It was really weird at first, but I think we all just looked at each other and knew he was here, he was with us. So, yeah, I have encountered otherworldly entities.

Featured Book

-

.

We Are a Haunting

By Tyriek White

Published by Astra House

Colly discovers he has inherited his mother’s gift of being able to communicate with the spirit world, and begins to slip into the liminal space between the living and the dead on his journey to self-realization. After college, he returns to the East New York of his childhood to work toward addressing structural neglect and the crumbling blocks of the public housing he was raised in, discovering a collective path forward from the wreckages of the past.

About Tyriek White

-

Tyriek White

Tyriek White

Tyriek Rashawn White is a writer, musician, and educator from Brooklyn, where he served at-risk and marginalized youth, artists, and scholars in the classroom. He is currently the media director of Lampblack Lit, a literary foundation which seeks to provide mutual aid and various resources to Black writers across the diaspora. He has received fellowships from Callaloo Writing Workshop and the New York State Writer’s Institute, among other honors. He holds a degree in Creative Writing and Africana Studies from Pitzer College, and most recently earned an MFA from the University of Mississippi. He is the author of We Are a Haunting (Astra House, 2023).

Photo Credit: Dan Henry