November 30, 2023

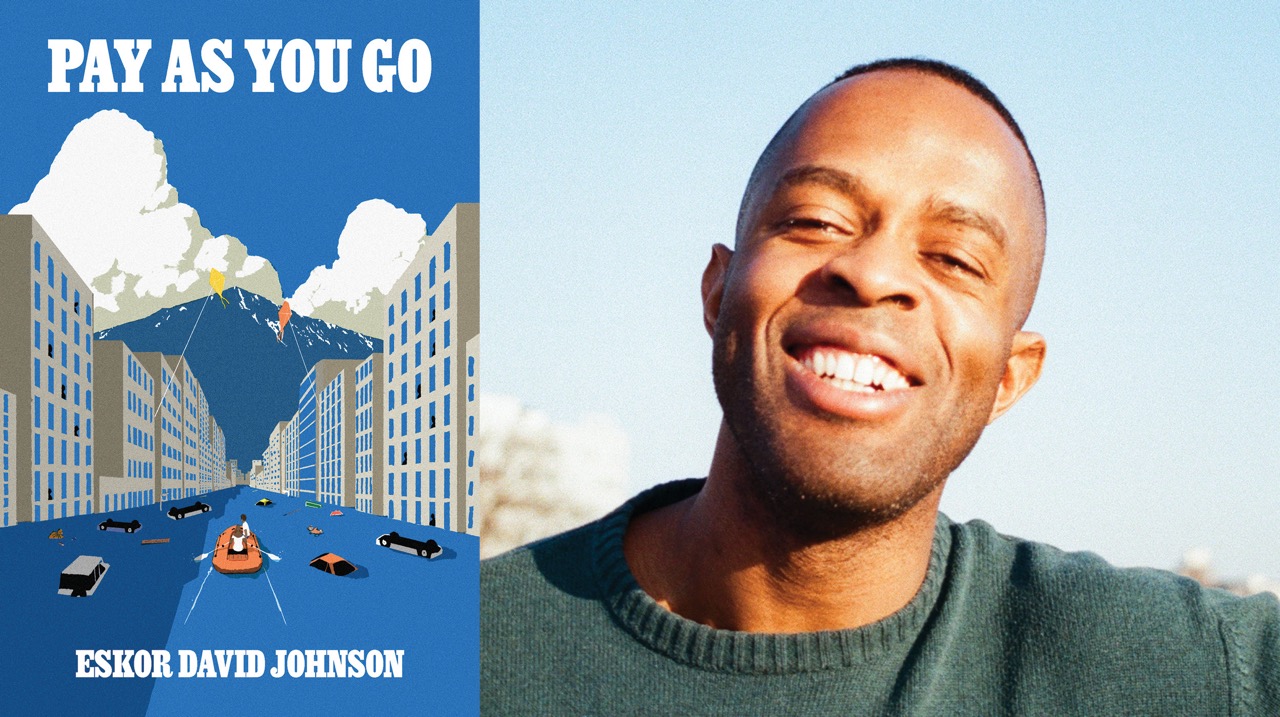

Eskor David Johnson, author of Pay As You Go, spoke with Becca Shapiro in celebration of being shortlisted for the 2023 First Novel Prize. The novel follows Slide on a fantastical quest across the city of Polis in search of a place to live after the reality of the rental market collides with his overly confident expectations for what his life will look like. Bouncing from foldout couch to disaster-relief tent and falling in with some tough types, Slide begins to realize that he’s going to have to scratch and claw just to claim a place for himself in this world—let alone a place with in-unit laundry.

What was the first seed for the idea of this book? What couldn’t you stop thinking about that led to creating this story?

In an unusual sequence of events, the title came first, which is not a way I would recommend approaching writing a novel. Back in 2010, I was traveling through Spain in the summer and a friend of mine was robbed. We were at the beach and we were all in the water, and when we came back all of his stuff was gone—his passport, even his pants, it was crazy. The next day, I’m accompanying him to replace his passport at the U.S. Embassy and he said, off the cuff, “You know, sometimes you just have to pay as you go.” He had just been robbed of everything, he had been upset the night before, and now he has this attitude of, like, “Okay, well, you just have to keep moving forward.” And I remember thinking, “Oh, that would be a cool title for a short story.” That notion of “pay as you,” having to move forward, stuck with me.

Then, I got to New York after graduating college, and I was trying to find my way in a big city, which could feel very vast and overwhelming and unkind, and I started to hear a voice that wanted something or needed something, I wasn’t quite sure what. Then all of these things—pay as you go, finding somewhere to live—came together.

Yeah, I remember my first year living here, I felt like I was almost unconscious for a year.

Yeah, like a fugue state.

Exactly, it feels like you enter this tunnel where there’s always goals—it almost feels like this weird video game with objectives and checkpoints, but you don’t know what you’re driving towards. And that’s how this book felt, like a video game in that way.

It’s a very simple approach to plot. I think there are many ways to do plot, but sometimes the most fundamental ones are the most rewarding. The simple notion of having a character on one end, and a desire on the other end, and then you just put obstacles in the way. That’s how games function too. And that’s how living in America in general, but in New York particularly, can begin to make you think about life. It’s this game-oriented objective where you have to achieve this, and do that, and if I do this it’ll allow me to do that. Americans are very good at speaking about their lives in a narrative sense. They do this more than most people I think.

I was going to ask you about that. How have your experiences living in other countries affected how you relate to this tendency to narrate one’s self-conception in America, and how does that relate to the book?

I think in a lot of other countries, in Trinidad for example, life kind of happens to you. You were going to do this, but then this other thing happened, and okay that’s just how it goes. You’re very much at fate’s whim. Americans wrangle fates. They’re like, “I’m going to do this, I’m going to do that, this is what’s going to happen in one year, and in five years I’m going to do that.” A lot of it goes wrong, obviously, but to give Americans credit there is a whole lot that they are able to achieve from having this approach to fate, setting these temporal checkpoints. That narrativization of your life was something that I learned from coming here, and I didn’t even realize it was a thing until after a few years of being here. So, I think the novel really takes that notion and exemplifies it. At one point Slide says, “The mission would be this: I was going to Polis and find a place to live. Not somewhere to eat, sleep, defecate, and wait for the reaper in this grim carousel, but to live.” It’s this thesis statement, in a way, and I think that’s a particularly American thing, to have this thesis statement for your life.

It’s interesting that you’re saying this enables us to set goals, and maybe it gets us two steps closer to something than maybe we otherwise would’ve, but then on the flip side it means we’re more at risk for being consistently disappointed.

100%. It’s an illusion. Even if you get the thing that you’re aiming for, which is not guaranteed, you get there and you realize it wasn’t anything like you wanted. Getting there isn’t the point, it’s everything else that happened along the way. It’s the fates, it’s the life happening to you. But that checkpoint allows you to fall into the illusion, it incorporates that randomness and those notions of fate into a ready-made package. You’re able to feel as if it all has some kind of meaning when really it’s all kind of meaningless. If you don’t have these goals, and you don’t have these notions of imbuing things with value, all that is left is this frantic action of human activity for no reason. Why are we doing all these things? Why are we building things? Why are we driving around and going fast and blowing things up? It makes no sense. But we need to do something or else we’re confronted with the abyss and the meaninglessness of our existence. So, the activities are important to ignore that.

We’re creating stories, essentially, to live in.

Which is why those stories are so important, because they allow us to not just despair. That’s what we should be doing. We should all just be like, “What the fuck are we doing? Why are we here? This is fucking crazy. Where did all of this come from? This makes no sense.” But, if we were to do that then we also wouldn’t be here. We’d quickly just fade out and die. These activities and these goals and these narratives are the most useful and powerful type of illusion that we’ve been able to make for ourselves as a species, as a culture, so that it allows us to spend the time enjoyably, or at least not despairingly.

Reading the book did make me think about why we tell stories, because there’s a cool meta story structure going on with Slide telling the story, and he’s conscious of the fact that he’s telling the story, which is one of my favorite constructions. I love that in a book. But it made me think about how weird it is that we as people enjoy telling stories and consuming stories. What you’re saying is making me feel like there’s somehow almost no difference between what it means to live and what it means to make a narrative.

I genuinely think so. It’s like storytelling as a means of existential survival. It’s why I knew, when I was thinking of the arc of this, that Slide had to be telling this to someone, and I knew that the telling of the story had to be essential to the result. It had to be that the telling of the story is how he’s able to reach some kind of goal, and I think that’s a metaphor for the way I think stories are important in our own lives. Going back to moving to New York, it’s so important when you move to this big city that you have a narrative for what you want to do, because it saves you from just being absorbed and overwhelmed and having this city eat you up and spew you out. Your story, your narrative, your purpose becomes this armor that allows you to navigate so much of what the city can do to you. So, with all the characters who share their stories with Slide, it’s not just that they’re doing it for fun, it’s how they’re able to become more real, and claim more space in this unforgiving landscape by having shared something, having told someone else, “Here he is who I am.” And if you don’t get to do that, if you don’t get to say to another person, “Here is who I am, here is why I’m here,” then the city can gradually erode you.

While the story is so centered on how Slide has this thesis, he’s also one of these classic protagonists where it is more about how he relates to these people who are telling him their stories, and they’re these forces that blow him in different directions and he just kind of goes with the flow, at the end of the day. How did you see his relationship with those characters?

Three things, I’ll say. Slide, he’s not “no, but” he’s “yes, and.” He’d be great at improv. Next thing, in a failed draft of the novel, Slide was not older in actual age but felt much older, he was insufferable. For Slide to have worked as he does now, I hope, I had to make him stupider but braver. A combination of those two things is what allows me to propel him forward. The third thing, to answer your question of how he is moving through all of these narrative winds, Calumet says to him, “Some of us, we die before we die. Others are like you, who can live a thousand lives before touching the grave. The price you pay is to keep our own stories with you.” I think that’s true of Slide. There are these figures in our lives—my grandmother was like this, my mom as well, and I would like to think I’ve taken some of those aspects from them—who can’t help but to be involved in life, and to be involved in the lives of others. They always have some story to tell, and they become such useful figures in communities for their ability to be so many things to so many people, and to be full of life. That’s what I think Slide has.

I was very perplexed at times as to why Slide is so likeable, because he’s complaining all the time, he’s inconveniencing people. But he not only wants good for himself, he wants good for the people around him too.

Yeah, because the book feels like it’s very related to capitalism and desire and climbing the ladder, but Slide actually doesn’t care about any of that stuff. He’s moving through that space but not propelled by it. He’s uniquely pure and you just want to hug him. It makes the book weirdly optimistic.

Someone described it as a dystopian narrative, with which I did not agree. I was like, if it is, it’s only insofar as the world in which we currently live is already dystopian. It’s a happy book, in a very weird way.

There’s that moment when he meets Osmond, his real estate agent, for the first time and Osmund says, “Tell me about the place that you want, tell me about your vision.” We would normally answer that question with, like, I want a two-bedroom, I want two-thousand square feet. But he says, “I have this friend who owns a cat and I want to be able to serve him cappuccinos and have some milk for the cat.” That’s what he wants. “I want my friends to come over,” and wherever it happens it kind of doesn’t matter. When he’s with the gangsters and he gets his own spot, he’s kind of content. It’s a crappy place in a dangerous part of time and he’s involved with all these shady characters, and he’s happier than he’s ever been. Then when he’s seeing all these fancy apartments, he’s saying he’s not happy there.

So, he wants to be present, to be human, and to share and give others comfort. That’s what he’s trying to find. But he doesn’t even know that, or can’t articulate that. He thinks it’s about an apartment, but he doesn’t want an apartment, he wants a home. And that’s what it takes him 500 pages to figure out.

I’m going through a little bit of that myself. I thought what I wanted was to publish a novel, and it’s been great. But you know what felt much better than publishing a novel? Writing a novel. Now I just miss writing it. I miss not knowing what was going to happen, having to figure it out. I miss seeing Slide do things. He says at the end there, after he’s seen all of these apartments, “The world had become my oyster but I lost my appetite. Now that’s sad.”

I think that’s one of the genius parts of the book. That “now that’s sad.” It made me aware of in my own life how sometimes you have those moments where I should really stop and have a reaction like that but I just move right through it. And maybe I should pause and really be conscious both of what’s happening and my reaction to it, since that’s part of it.

I was going to say we struggle with this, but it’s also our gift where we’re trying to live life and observe life at the same time, and sometimes it stops us from being as present in a moment because we’re already trying to formulate it into this narrative.

It’s like those writing exercises where they say, “Observe. Write about the space.” And you stop and realize, oh my gosh, everywhere I go, everywhere I am, I could stop and I could write for hours about the space.

That was part of the challenge in writing Slide, because I wanted him to feel both immersed and that he’s observing. You don’t want it to feel as if it’s someone who’s not in things, who’s just walking about observing things, which in earlier drafts was part of the problem.

How did you combat that?

It’s hard. The “yes and” was important. I needed those moments where I had to think, what is the version of this where Slide is just seeing something happening and what is the version of him getting implicated in some way? For example, there was the key moment when he gets off the train downtown for the first time. Now, in crafting a narrative, the story structure of this is that we’re in the first part of the hero’s journey, where the hero has been in a place that is known, and then something happens that thrusts him out into the wider world. So, when he comes up from the train, now he’s out in the world. From a writing perspective, the challenge there is that you now have a lot of world building to do; you have to show this bigger, wider space, but at the same time you can’t just stop the story to have to do all that, right? Pause, look around, here are the buildings, here’s the map. There’s a lot that needs to be done in a very condensed space, and in the earlier drafts it wasn’t working because he was just observing while he was walking and I just didn’t know how to get him from A to B. The solve for that was, when he comes up, he has to pee.

Which is great because the number of weird excursions you have to do in the city purely from needing a bathroom…

It’s crazy. So now, you still get to catalog all those sites and sounds of the wider world, but it’s getting done in this context of this driving need. He’s zooming through everything without the patience to appreciate everything. So, instead of indulging me the writer like, “Look at all this stuff I’m making in front of you,” he’s just like, “Fuck, this building’s not letting me pee, that building’s not letting me pee, I’m going down this street and that street trying to find somewhere to pee.”

At what point did you know the end?

From the beginning, I knew he was telling the story to someone, but I had no idea who, no idea why. Then I write the scene on the mountain where Jim and Jean from the news arrive, and I realize, oh, he’s telling his story to them. When I put my finger on that it’s like, okay great, so Slide is saying this on TV. There has to be a reason for it. Maybe by telling this, that’s how he’s able to find somewhere to live. The writing got much easier from the mountain onwards because I knew it had to land with him getting onto the show.

Jim and Jean don’t really get their own stories to tell and, as you say, giving characters narratives gives them meaning. Why did you choose to leave them disembodied?

They’re the muses. You need to invoke the muse to have the permission to tell your tale. You bow down to these figures on high who imbue us with the ability to speak these tales. It was never a thought in my mind that they would be more real. They’re just figures on TV, and how real are the figures on TV to us?

It’s interesting that these disembodied talk show hosts are what enables Slide to become a person himself.

There’s a happy and an unhappy interpretation of that. It’s a happy result, it’s a happy ending for him. But, that ultimately still speaks to, no matter what we try to do to combat these domineering capital and commercial forces that are the very things making your life so hard to live, they’re also the only means through which one is able to find some kind of salvation.

Featured Book

-

.

Pay As You Go

By Eskor David Johnson

Published by McSweeney's

When the reality of the rental market collides with Slide’s overly confident expectations for what his life will look like, he embarks on a fantastical quest across the city of Polis in search of a place to live. Bouncing from foldout couch to disaster-relief tent and falling in with some tough types, Slide begins to realize that he’s going to have to scratch and claw just to claim a place for himself in this world—let alone a place with in-unit laundry.

About Eskor David Johnson

-

Eskor David Johnson

Eskor David Johnson

Eskor David Johnson is a writer from Trinidad and Tobago and the United States.

Photo Credit: Kimberlee Chang