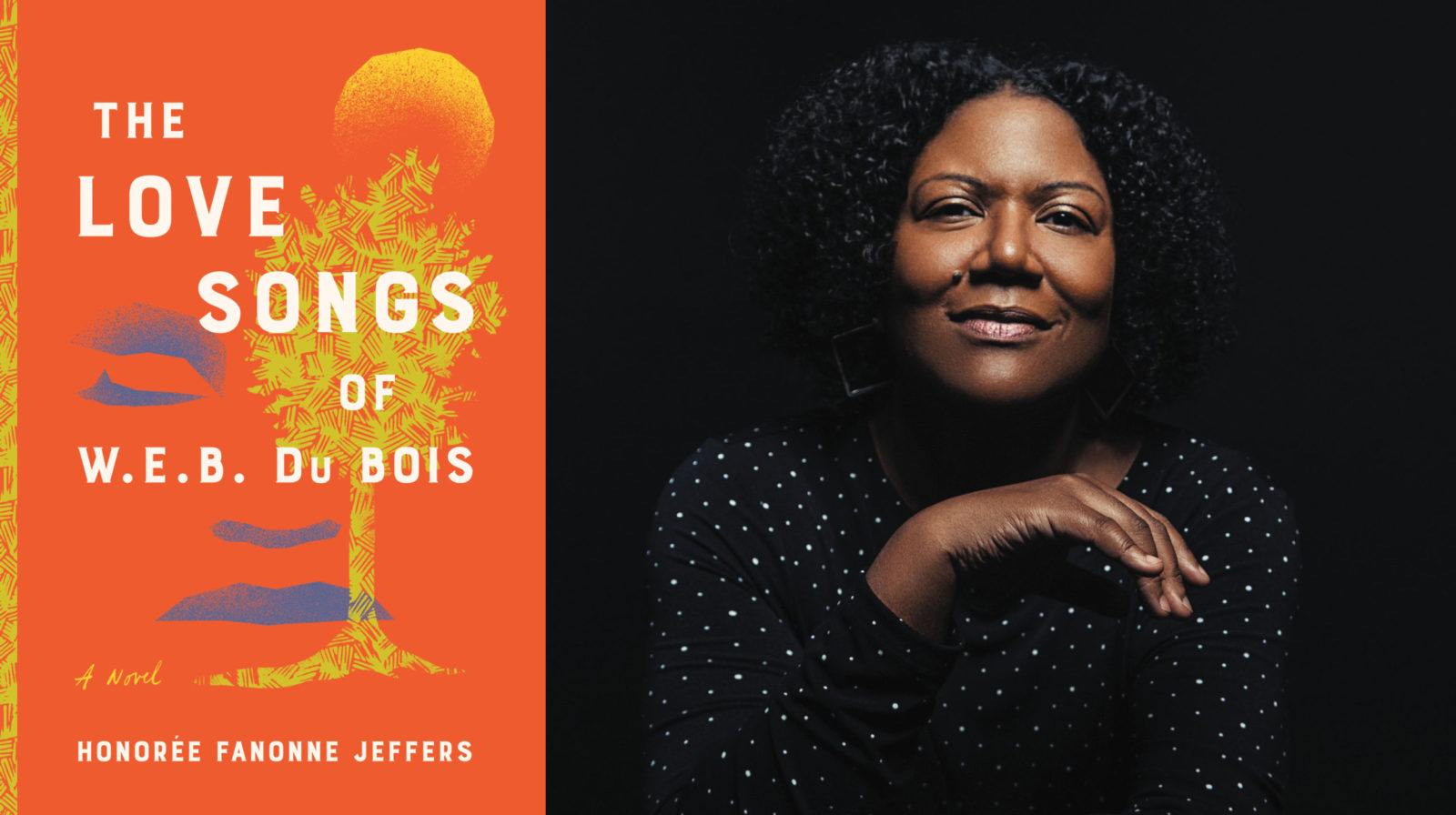

Melanie McNair, Senior Director of Public Programming, interviewed Honorée Fanonne Jeffers, author of The Love Songs of W.E.B. DuBois, in celebration of being shortlisted for the 2021 First Novel Prize. The protagonist of The Love Songs of W.E.B. DuBois, Ailey Pearl Garfield, embodies Du Bois’ concept of “Double Consciousness” even with her namesakes—the revered choreographer Alvin Ailey and her great grandmother Pearl, the descendant of enslaved Georgians and tenant farmers. To come to terms with her own identity, Ailey embarks on a journey through her family’s past, uncovering the shocking tales of generations of ancestors—Indigenous, Black, and white—in the deep South, reflecting a legacy of oppression and resistance, bondage and independence, cruelty and resilience that is the story of America itself.

What was the first kernel of the idea for this book? What couldn’t you stop thinking about that led to creating this story?

My maternal ancestors are from Eatonton, which is a small town in central Georgia, and when I was a little girl I would go to visit my grandmother Florence with my two sisters every summer. There were lots of relatives in the town and even for those of us who weren’t related, everybody knew everybody. We would work in the garden and listen to her reedy voice sing traditional Negro spirituals, and we would sit on the porch and we would fan, and everybody would come visit. It was just a very idyllic time. So when I began to think about happiness, when I got to be an older person, I thought about Eatonton.

I began to create this town in my mind that was similar to Eatonton populated by people that I didn’t know but that reminded me of that sort of place. Then I began to think about the history of the place, and then I began to think about the relationships between the people in that place, and then the next thing you know I had a whole town. I never really knew Eatonton as an adult, so that’s why I made up a town, Chicasetta. I did the same thing with “the city.” People are saying, “Oh, this is Washington D.C.,”but I don’t know Washington D.C. This way I could create all of the geographic locales, the historical markers, and all of that, and not get in trouble.

What were your biggest challenges with writing this book?

The biggest challenge was how to merge the contemporary story with the historical story. The historical story, as you know, is called the songs and the songs are woven through the contemporary story. For several years, probably about 4 or 5 years, I was very confused about how I was going to intersect these stories. Once I figured that out and how these contemporary characters would mirror what was going on in history then it became a bit easier, but that was around year eight.

I’d say one of the more difficult parts of the writing process is I had people who passed away. My mentor, the great poet Lucille Clifton, passed away in 2010. My best friend James William Richardson Jr., passed away in 2011. My sister passed away in 2014. My marriage died in 2015. So there was a lot of emotional struggle during this, and then when I was in the middle of line edits it was the first year of the pandemic.

What was your writing practice like?

At the beginning, I would get in where I fit in. I teach for a living and I’m very lucky that I have tenure, and I teach at a research institution so I was only teaching two classes a semester. But there’s a lot of emotional energy in teaching and there’s all this other stuff going on, so I didn’t have a lot of time. I would bring a notebook with me to work and nibble on it there.

It’s always scary when you first start wrapping your head around what the project is going to be. I was fortunate with Love Songs that I never knew the historical portions were going to be part of the book until 2 years in, and I think if I had tried to wrap my head around that it would’ve been too daunting and I would’ve just been a coward and stopped. But, once I got a bit of a groove, I found more of a routine. I get up early—just naturally, my body will wake me up at about 4.30 a.m., sometimes 3:30, I think that’s the sharecropper stock in me—and I write for maybe 90 minutes. If I’m really hitting a groove, maybe 2 hours. Then I’m exhausted, and I go back to bed. I do not have morning classes, I’ve learned better. I take a long nap, maybe 3 or 4 hours, and then I get up and answer emails and do the other work of the day. I give everything I have to the writing in the morning and then, as the great poet Mary Oliver once said, I give everyone else my very second best. People don’t seem to notice that it’s my very second best, they think it’s my first best, so thank God for that.

I write longhand, so there are notebooks on top of notebooks on top of notebooks and everything is disorganized. I’m writing across the page, I’m writing little notes, I just kind of free write. If there’s a word I feel like I’m repeating too much I’ll do something like write “[new word].” Once I have about 10-15 written pages, then I’ll type. Once I type, I edit as I go, and it’s very easy and it’s very natural. Then I’ll edit again, and then I’ll edit again, and again and again. As you know I’m a poet, so I’m very particular about the line. That probably slows me down, but as a poet the line, the word economy, is very important to me. Also the more pain that you have, the more beauty that you have to have in order to comfort the reader as they move through these sentences.

I’ll say that when your publicist told me, “I have this first novel by a poet, would you like a galley?” I said absolutely, I love novels by poets. And then I got it and was like, “Wow it’s over 800 pages!”

My big chunky baby!

But it needed to be and it was perfect at that length. It’s the whole story of America in so many ways.

It’s a long book and I didn’t intend for it to be that long. At first I said, am I trying to just get everything in here in case I never write another novel? But no. For every 100 pages that you see there’s another 200 or 300 pages that aren’t in that book. People wanted to see the stories of all these characters, but I kept having to choose whose story to write or to not get into. For example, Coco. People wanted to see the story of Coco, but I felt like I didn’t have the skills yet to write a LGBTQ character to the best of my ability. I was already writing an Indigenous story, and I was really afraid of being dragged by Native American scholars. It was going to take a lot of research. I’m very obsessive, and even if I don’t use the research, it shores me up so that I know that I’m representing an image or characterization that is realistic, and I knew that was going to take me about 3-4 more years. But now I feel like I’ve got my skills together, and I’m really excited to get into those stories, and not because it’s “important.” I don’t write aspects in a book like Metamucil fiber. I don’t really care if it’s important or not, it’s whether or not it’s in my heart, and it’s been in my heart for a really long time. There are a lot of people who got cut, but that’s why there will be short stories. I’m always going to be coming back to Chicasetta. We’re never gonna leave.

You just spoke to this a little bit, but what are some larger conversations or topics that your book speaks to or engages with?

The biggest conversation that my book speaks to that I wasn’t aware of until we got into line edits, believe it or not, is how did we come to be into this place called America the way that we are now? The past 4 or so years have been harrowing for this country, and I was not prepared for that. I was not preparing for the book to feel timely. Half of the book is historical, and I thought people will be like, “oh this is how we came to be here and now we’ve moved past it and now we’re moving toward this more perfect union.” This is the point you get to in a Lifetime Special Move for Women where you get that soundtrack, dun dun dun dunnnn.

Then what happened is I began to understand that my book was much more of a larger project. It still makes me uncomfortable claiming that. People are always sort of shocked at how playful I am considering how my work is so serious, but you can’t always stay in that place all the time. I mine what is serious and the hurt and the pain and the intellect, and I leave that on the page. But I don’t believe in shoehorning issues into a book. I realized in line edits that this was a book about how America came to be and that was the question that had been tapping at the back of my skull all along. How did we get here as a country? How did we get here as a region? How did we get here as a Black community? How did we get here as a Black family?

I know that people still find racial markers useful, but for me it’s both very important and not important that they’re Black because they’re American. I’ve had people ask me why did I feel it was important to write about Black people or Black women, and I know they don’t mean any harm, but Professor Toni Morrison told us to stop asking those questions because we never ask a cisgender white man, “Why did you feel it was important fo write about a white man in the wilderness,” or whatever. “Why are all of your characters white?” No one would ever ask that question. Yet they still feel comfortable asking that question of Black writers, and I want us to get past that because we are America.

Along those lines, to an interviewer’s question about the audience Earnest Gaines was hoping to reach, he responded, “I write for the African-American youth in the country, especially in the South so they can know who they are and where they come from so they can take pride in it, and for the white youth of the country, especially in the South, because unless he knows his neighbor of 300 years he only knows half his history.” So your book contains histories of people from European descent—Scottish people mostly—African Americans, and Native Americans. What audiences do you hope your novel reaches?

Anybody that picks up the book is the audience that I want to read it. I feel like there’s something for everyone.There’s so much history in the book, and it would benefit anyone to read it. I was very shocked—the most beloved character in the book is not Ailey, it is Uncle Root, and Uncle Root is an historian and he’s a professor, and Ailey is mentored by other history professors. The spine of the book is American history, and southern regional history, and indigenous history, and English history, and Black history. All of that is American. There’s something for people who want to know about the history of this country without yawning. That’s what I think people don’t understand, the best history reads like a novel.

It’s wonderful when I see “regular” Black folks—which is to say Black people who are not academics, Black people who have never read a book this long—saying I was scared when I picked this book up, girl, but it went so quickly. And then I want white folks who don’t know Black people to see a version of blackness that I have created not out of fear of insulting white people, but for them to be a fly on the wall and to hear these conversations that black people have when no white people are in the room. Sometimes when I’m on Instagram Live and a white man wants to come up and join us I’ll say, “This is a Black space and you’re welcome to be here and listen and learn, but the moment you’d come up the whole dynamic would change.” It’s not to reject him but because I’m gonna be afraid, I don’t want to hurt his feelings. Or then also you get into spaces sometimes with white people and you’re talking about Black things and they’ll say, “I’m white but I think,” and I’ll say, “Stop right there, this is not your conversation.” Again, not to be harsh, but that’s what my grandma and the old folks used to say when I was little. “Pay attention to me, baby, and you might learn something.” If you’re always dipping in then you’re not listening. So this is a book for people who really want to know, and some of the things that they’re learning are not necessarily great. This is not a book that is Disney comes to slavery. This is a realistic book based on realistic history. White people in the South were mean.

Somebody always wants to see a book about an interracial friendship in Jim Crow era, in slavery era, because they want to lie to themselves and think if all we would do is be nice to each other everything would change. They don’t want to look at the structures that make it nearly impossible even for white allies to be nice, that make it Herculean for them to try to change their society. Those structures are in place so if you get a nice white person they end up being deeply discouraged, and we see that at one point in the book. That’s what I want people to really understand. You get shunned socially. There were a lot of laws that would put people down South in jail for trying to free slaves, for teaching enslaved people how to read and write. You couldn’t marry even free black people. There weren’t laws against sexually assaulting black people, it was a crime against property.

Yes, this is a book that’s a love song for Black women. But I wanted to show people of all different races because I want people to understand just how truly difficult it is for us to love each other across these racial lines, to have friendship across these racial lines, if there is this power structure in place that privileges one of us over the other.

You were already a prolific writer but since this is your debut as a novelist, what do you hope this book says about you as a fiction writer?

I labored for a very long time, for 24 going on 25 years. Today it was announced that Love Songs was a New York Times Notable Book of the year. I’ve written 5 books of poetry, I’ve always wanted to be on that list. Every year my book was ignored. The last book got a little bit more attention, but still. There were years that I was jealous, but I got past that, and I had to understand that it’s not lists and prizes, that it’s about the work and it’s about the body of work that I’m building. It’s not about one book. When people see this one book they need to know that the books that I’ve written before all led to this book, and you can see a continuum between these books, and if God willing I publish essays, if I publish other books, people will continue to see that connection.

Every book that I write I lay it all on the field because it might be the last time. I want people to understand that my work is not simply about lifting up my ego and lifting up my career, it’s about leaving something of worth that will help people and will help this country after I’m gone. That’s the tradition that I come from. When you look at African-American literature and, if I may even though I’m not part of the community, if you look at Indigenous literature you can see that, you can see that there is a purpose to the work.

One of the things that I loved about your novel, especially as somebody who grew up in the South, is the food, especially the love language of dessert, which might be one of the reasons why Uncle Root is one of the favorite characters in this book.

He’s always got a pie!

Exactly! So what I want to know is, as we move towards the holiday, what kinds of pies are on your mind? What are you looking forward to eating or making?

You know, it may disappoint people, I’m not a holiday person. I typically just kind of lay in the cut during the holidays because that’s really the only time I have to rest. But let me say that, you know, every Black family in America with very few exceptions is going to have a sweet potato pie on the table. That’s because food is an archive, and in my book food is an archive. It’s not just about pleasure and the appetite. It is a love language, but it’s also an ancestral language. The foods that we African Americans eat now, we ate back in the day. Collard greens, turnip greens, ham hocks, grits, sweet potato pie, candied yams, etc. These dinners, these family reunions, this is how we keep the community together. Our communities were broken during slavery—I’m trying not to get choked up—but our communities were broken. My mother’s great grandmother Mandy talked about her father being sold when she was a little girl and she never saw him again. Many of the folks that are supposed to be spoken about, all we know is “never seen again.” This bringing together of family is not simply about eating this delicious food, although that is a joy, but it’s also about remembering those who aren’t there. It is a love language, it’s a love language for my people.

Featured Book

-

.

The Love Songs of W.E.B. Du Bois

By Honorée Fanonne Jeffers

Published by HarperCollins / Harper

Ailey Pearl Garfield embodies W.E.B. Du Bois’s concept of “Double Consciousness” even with her namesakes—the revered choreographer Alvin Ailey and her great grandmother Pearl, the descendant of enslaved Georgians and tenant farmers. To come to terms with her own identity, Ailey embarks on a journey through her family’s past, uncovering the shocking tales of generations of ancestors—Indigenous, Black, and white—in the deep South, reflecting a legacy of oppression and resistance, bondage and independence, cruelty and resilience that is the story of America itself.

About Honorée Fanonne Jeffers

-

Honorée Fanonne Jeffers

Honorée Fanonne Jeffers

Honorée Fanonne Jeffers is a fiction writer, poet, and essayist. She is the author of five poetry collections, including the 2020 collection The Age of Phillis, which won the NAACP Image Award for Outstanding Literary Work in Poetry and was longlisted for the National Book Award for Poetry and the PEN/Voelcker Award. She was a contributor to The Fire This Time: A New Generation Speaks About Race, edited by Jesmyn Ward, and has been published in the Kenyon Review, Iowa Review, and other literary publications. Jeffers was elected into the American Antiquarian Society, whose members include fourteen U.S. presidents, and is Critic at Large for Kenyon Review. She teaches creative writing and literature at University of Oklahoma.

Photo Credit: Sydney Foster