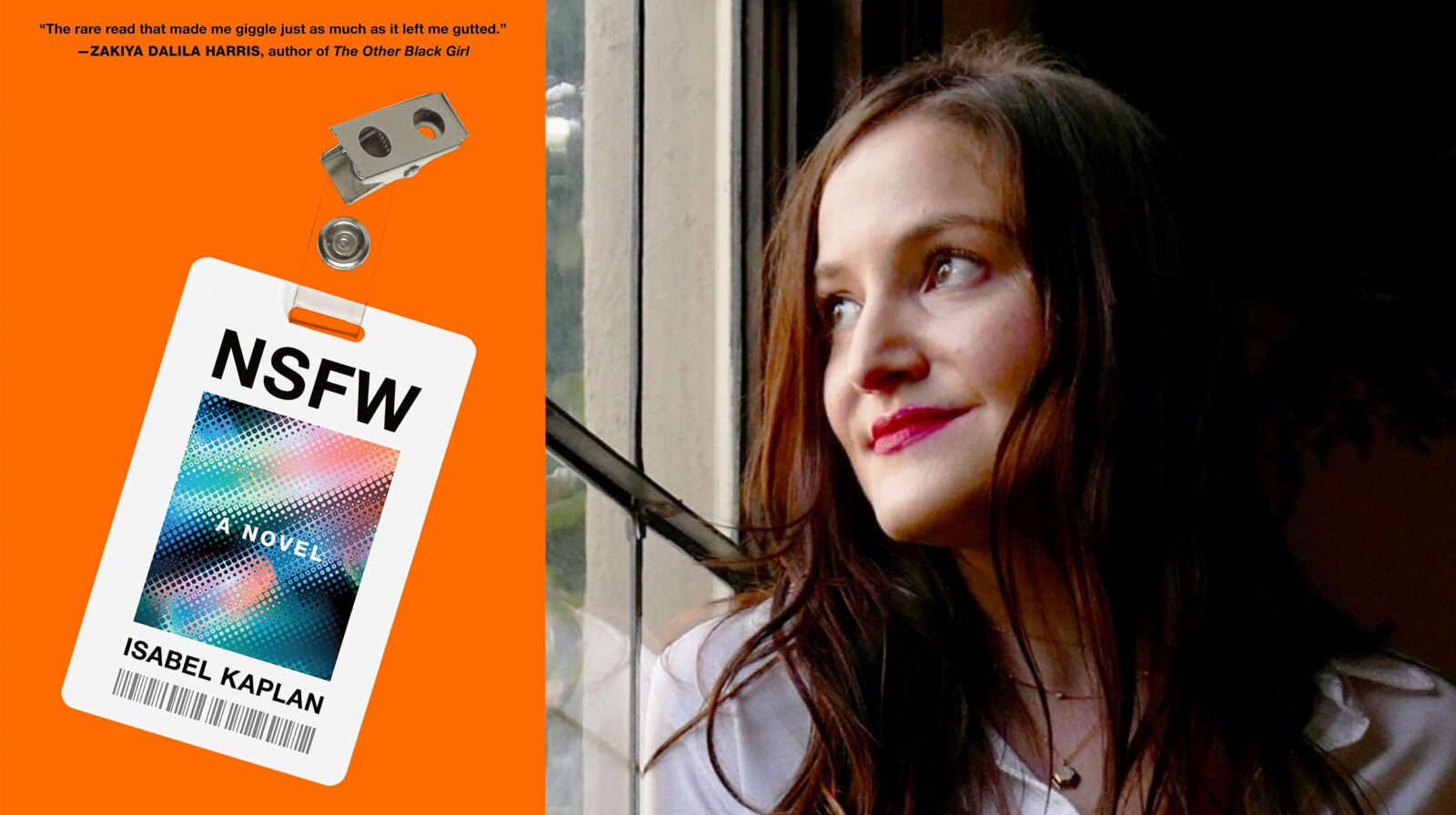

Isabel Kaplan, author of NSFW, spoke with Celeste Kaufman, The Center’s Manager of Marketing and Public Relations, in celebration of being shortlisted for the 2022 First Novel Prize. In this story about the gray area between empowerment and complicity, a young woman struggles with how much she is willing to compromise her feminist values as she navigates around sexism, harassment, and assault while building a career for herself in Hollywood. Her toxic relationship with her mother, a renowned feminist attorney, whose own morals have been diluted from a lifetime of success in a male-dominated industry, both helps and harms her ambition as the personal and professional come to a head.

What was the first seed of the idea for this book? What couldn’t you stop thinking about that led to you creating this story?

I started writing it in the beginning of 2017, my first year of grad school. I had left LA the previous fall, so I had been out of LA just long enough to start thinking about it. I was also thinking a lot in the wake of Trump’s election about the idea of whether or not it’s possible to make change within a system, this idea of whether or not female empowerment and working within a system and making change from the top is just this really elaborate lie meant to keep people in place and to prevent change. I was starting to question my own complicity in systems that I thought I was fighting against and fighting for change within, and that kept nagging at me. I was thinking about not just the most horrific abuses of power and gender discrimination, but the vast murky grey area, which is where most of us live. I started writing when I was in a workshop that was almost all male—there was only one other female student—and while a lot of my male classmates were wonderful, I found myself really intensely wanting to channel a deeply intimate, deeply vulnerable, deeply rage-filled female experience. I think there was an intensity there that started blending together into writing what became NSFW.

What were the biggest challenges while writing the book?

Cutting things. I have never been someone who’s capable of outlining. Each time I think, “Wouldn’t it be great if I could have an outline? This time I’m just going to write it straight through, clean, nothing extraneous.” But that’s just not how my brain works, I’m just not built for that. So I would amass material that I really cared about and was proud of, and it was a painstaking process of figuring out which scenes I’m really attached to because I like them versus which scenes serve the plot. I went through so many revisions and became pretty ruthless about it, but there were some that I still felt very sad to lose. I knew that once the book was done I would feel better about it, and I do, it is the book that I wanted it to be, but in the moment when you spend an immense amount of time on a chapter, it’s really hard to say okay this all has to go.

Do you do that thing where you have a separate document where you keep all the stuff you cut just in case?

Yes, compulsively. If I didn’t, I don’t think I could function. “Cutting Room Floor,” is what I call the document.

What was your writing process like? Are you someone who’s very regimented, same time every day, a certain amount of words, or do you just write whenever inspiration strikes?

I have to be sort of regimented because then I won’t get anything done. I’m extremely deadline-motivated and accountability-motivated, and so I’ve found that the more I push myself to write regularly, the more I will actually get written. So, basically, all of my writing tips are tricks to get around my brain stopping me from writing. I wrote most of the first draft long-hand, largely because that’s the only way I could slow my brain down enough and trick myself into thinking this is a rough draft. I could assure myself that I’ll type it up later and then it’ll be a rough draft that counts, but right now on this page these are just nonsense words, I’m just trying to get through things. By telling myself that I actually enabled myself to be really free and creative.

In the early months of writing, because I was in grad school which was such a wonderful privilege, I did five handwritten pages five days a week, and that’s what I stuck with for a long time. Now I have a full-time job and it’s a little trickier with time, but I’ve learned that I can’t write at night. If I wait until the evening I won’t have any energy left, and so it’s basically morning or not at all. I come up with fake deadlines for myself. I make my agent come up with fake deadlines. I tell people when I’m planning on finishing something by. I know that if I do it and I keep track—I literally keep a handwritten log—then I’ll get more done. But if I don’t pay attention to it it’ll somehow be a month and I haven’t written. I was definitely less productive during publication but I’m slowly getting back into the rhythm.

Do you have a favorite notebook you want to shout out as someone who writes by hand?

I’m left-handed and this is a big perennial issue because I smudge everything and I have to be very careful. I love Apica notebooks. There are two deeply random brands that are basically Moleskine knockoffs with much thicker paper, and those are Lemome and Paperage, which are like $8. I do that for my note taking, my journaling, but when I’m drafting honestly I use just a plain Clairefontaine spiral notebooks or a legal pad. I take notes that feel more important in those smaller ones but for some reason the legal pad feels like there’s not that much pressure. These are just thoughts, this isn’t a special notebook, it’s just a random thing. Somehow that helps, making it not precious. I will say it was super satisfying to recently find all of the notebooks from the process of writing this book and hold them.

So, we also usually ask what larger themes and topics of conversation these books engage with. I feel pretty comfortable saying yours is about sexism and sexual harassment and assault in the workplace primarily, so to go into that question from another angle, when I was reading about this book before it came out it was very much promoted as this kind of Me Too type of novel. I thought to myself, “Oh I know how this story is going to play out.” But as I was reading it, as you sort of alluded to in the answer to the first question, it’s much more about complicity in these oppressive systems and subverting expectations of what we’ve come to expect from these Me Too narratives. The ethics of the characters are a lot murkier than I anticipated. So, if you started writing in the beginning of 2017, that was right before Me Too started, but then it was playing out as you were working on the book. How did writing this book as this larger movement was unfolding shape the book, especially in terms of subverting these expectations we have for these narratives?

Right, the Me Too movement itself isn’t in the book at all. It’s set in the later Obama years, in 2012. I remember some people were saying how convenient, how prescient, and what good timing, but these aren’t new issues. I’ve been thinking about these things for a long time. I think what we’ve learned over the course of the Me Too movement is how badly, culturally, we want stories of good guys and bad guys. We want to call out oppressors and we want to rejoice when victims speak out and share their story, and we still want victims to be good victims. The Harvey Weinstein story is horrible and egregious and that’s why it became this central example because the moral clarity was there. But I don’t think we’ve come up with a good way to discuss the messy gray area. Most of us aren’t in a situation where we’ve been invited to a hotel room and are faced with a Harvey Weinstein, but almost every woman I know has been in a situation where they felt uncomfortable at work in a way that they couldn’t quite put a finger on, and because they couldn’t figure out a way to identify it they sort of internalized the blame and made it their problem. I was much more interested in the subtle ways that experiences accumulate and how you can end up as the frog in the boiling pot of water where you’re burning up and you don’t realize it and now it’s too late.

As I wrote, I watched Me Too play out and I realized I was getting a lot more pessimistic about the ways that we were talking about the cases and the women involved, and the ways in which speaking out and sharing your story were being presented as a moral good and a thing that is empowering, but it’s often not. The problem is that as soon as you speak about it that becomes the thing that you’re known for, and that’s sort of the trap. There’s so much more to everyone’s identity in life than having been a victim of sexual harassment or sexual assault, but as soon as you speak up about it that does become the whole narrative. Honestly, ironically, I’ve felt that’s sort of the case in my own publicity of the book. I think of the book as being about the experience of being a young woman in the workplace, and boundaries between personal life and professional life, and relationships between women, and the ways in which women support and police one another. And it is true that nearly every woman in the book experiences some form of sexual harassment, which is true of nearly every woman I know in my life, but that doesn’t mean that’s their central defining feature. But, the problem is that you don’t get to choose if that’s something that matters or that you care about, it’s a force acted upon you. I find that’s what I’ve been speaking most about and it’s interesting because it parallels the experience and the fears that I think so many women have about the value of coming forward. If I do come forward, is it just going to be another story that keeps repeating and repeating? No one wants to hear the messier parts, which is that we’re all still stuck in the same systems. A few men are gone, but basically, every structure still exists.

It’s so fun to think about, isn’t it?

It is, and I also wanted to do it in a funny way, which is a weird and hard thing to explain because I feel like when I speak about these issues that I care very deeply and very seriously about it makes you feel like you’re going to get a serious dogmatic feminist tract, and that’s not what I wanted it to be at all. I also wanted it to be really funny, and funny in the place where it’s funny until it’s devastating.

I’m glad you brought that up because it was one of the things I liked most about the book that I couldn’t figure out how to formulate into a question. There were times when I was laughing out loud and it felt more like a fun story and then all of a sudden you’re really angry or upset or sad about what happens on the next page. I also wanted to talk about the relationship between the protagonist and her mom, which is complex, to say the least. Do you consider examining that relationship between the two of them an additional layer to the story or were you seeing it as something intertwined with those examinations of female empowerment and sexism and how women work together to combat these types of things? What role do you see that relationship playing in the overall story?

To me, that relationship is central to the story and it’s a part of the same narrative. It’s intense and complicated and messy and full of those murky gray areas that I’m most interested in. I think what was particularly interesting for me there was that it wasn’t just the boundaries between work life and family life and when those collapse, it’s also that the mother is a lawyer who has been to this movie before, so to speak. She has spent decades advocating for victims and victims’ rights and she has seen what happens, and those experiences have affected her deeply. At the start of the book, the protagonist is 22 and she considers herself fiercely principled in the way that you can only be if your principles haven’t been tested yet. She feels outraged at some of the things her mother is doing, but I wanted to show how and why people make complicated decisions that when they’re distilled to an 800-word news piece the complexity is stripped from it. I wanted to explain how people end up doing things that might seem to go against their purported values systems and how all of those forces and all of those influences are deeply intertwined.

One of the more complicated things is that a lot of the professional advice that the mother gives her daughter, it works. It’s useful, and that doesn’t make it good, and it doesn’t make it feel good, and it’s full of playing into a system, but it’s effective for her. I wanted the character to really sit with that. Does it work to just keep your head down and do the work until you get to the top, or is that a trap? So, for me it’s all of a piece, it’s all the same story. It’s about women and how the relationships between them can be the thing that builds you up and can be the biggest source of strength against the patriarchy there is, but it can also be devastating. We have a much harder time talking about how some of the bad guys aren’t all bad.

Yeah, I thought it was also just an interesting way of encapsulating the intergenerational issues of feminism, especially when it comes to physical appearance and playing into losing weight and dressing up and all that type of stuff, where I found her a very frustrating character, but I knew exactly that type of woman. I still felt sympathy towards her and understood where she was coming from, though.

Yeah, I always try to write with empathy and understanding. I think characters aren’t interesting if you treat a character as anything less than a human you’re trying to understand, so that’s always what I’m going for. A lot of the intergenerational stuff was very much at the forefront of my mind, things like diet culture and body image and girl power and the girl-boss narrative and the ways that our understanding of all of those things have shifted a huge amount just over the course of my lifetime, to say nothing of the past sixty years.

Your protagonist is unnamed. Something that’s interesting about working with debut novels each year through this prize is you pick up on these trends that happen for what’s being published each year, and I’ve read several books where either the protagonist or other main characters were unnamed. I was curious about both your own personal decision to leave the protagonist unnamed for this book, and if you have any thoughts on what this trend might indicate about what people are interested in reading and writing about these days?

For me, the decision not to name her was connected to the themes of individual identity and agency that I was exploring, and the fact that at the start of the book the narrator feels very much bound up in her mother’s identity. She’s her mother’s daughter, she’s struggling to figure out what her sense of self is apart from her mother and to create an independent identity. Then she moves into the network system where you only matter in relation to your boss, and you’re the appendage of someone else and your individual identity is irrelevant. Some assistants don’t even have their own email addresses, it’s just “assistant of boss’s name,” and I think living in that reality underscores just how replaceable you are, how insignificant your role is. That makes you think about how it doesn’t matter if you’re uncomfortable—if you’re unhappy, you can just be cycled out and you don’t matter in this system. Your fight to get to a place in this system where you do matter requires that you invest fully in this, and by the time you’ve invested fully then you’re sort of stuck there.

I think as far as the trend goes, correct me if I’m wrong, but I think most of those come from young women novelists. It’s a very gendered trend. I think that probably has a lot to do with these same themes of self-expression and agency and owning your identity. I think there’s also this desire to make everything universal, that these characters are meant to be any woman. But, a lot of those books are told from the first person and they’re told from deep inside that person’s head, and I think there’s an intimacy and an urgency to it and this desire to inhabit the self of that character. I’m curious to see if we see more or less of that going forward.

I have these grand existential theories about the loss of self.

It is the loss of self! And if we’re getting really broad with it, there’s also the assertion of self that is writing a book. You can explore themes of loss of self and lack of voice and identity and agency within a book, but the act of writing it and then publishing it is very much the opposite. You get to claim narrative agency and voice by writing the book. There’s this interesting sort of irony there. Or maybe it’s not ironic, maybe it’s very deliberate.

You touched on this a little bit earlier, but in addition to all of the things about sexual harassment and assault and sexism, this is essentially a workplace novel and a career novel. I’ve been really interested in how these types of stories are evolving as all of these conversations are happening and shifting attitudes are happening about labor and capitalism. I was curious what inspired you about writing about work?

I hadn’t read that many novels which were really about work. There are tons of novels where people have jobs, but they’re not set at a workplace. I think some of that is because that sounds boring because work is boring, but work is where we were raised in this late capitalist hell space and spend so much of our lives, and it bleeds into all aspects of our lives. The idea of not centering that doesn’t feel true to life, especially for the experience of being in your early twenties. So much of being in your early twenties revolves around embarking on a career and investing so much of yourself into work. You end up living in a way where you feel like you have a full life, you have a full social calendar, you have lots of friends, and you can forget so much of that is adjacent to your work. So many of your social events are connected to your work, and our friends are people you’ve met through work, and we identify so much with our jobs.

I think it’s really interesting to see now—and the pandemic has helped with a lot of this— there’s this huge shift questioning the value of that, and not just whether the workplace is good but the inherent problems of creating the system where that’s how your identity is shaped. Or, for example, that your health insurance is tied to your employment and not being a fundamental human right. I think all of those discussions are so wonderful and so valuable and so necessary, especially for young people, because a lot of these jobs are not sustainable. They’re not accessible to people who don’t come from family money or have a support system. Those conversations got pushed down and papered over before because enough people were willing to put up with the jobs. It does take a huge number of people and it takes organizing to change any of that because one person saying, “Hey, this is unfair,” doesn’t do anything.

But there’s also so much humor and so much absurdity and so much story that comes from being in a workplace, as anyone who’s ever been in a workplace knows. It’s this own world that contains all of the power structures and all of the power struggles and the absurd interpersonal dynamics that make up the great stuff of stories.

This novel has an ambiguous ending and I won’t give anything away, but, the protagonist has a choice to make and we’re left not knowing what path she ends up choosing, I think that’s vague enough. I wanted to ask you a question that I think directors get asked about their movies, which is do you know which choice she made—and you don’t have to tell me, even though I want to know—and what intrigued you about having an ending like this?

I think what mattered most to me as I was writing it and structuring it was that either choice would make sense and would be supported by anything leading up to that. It was really important to me that either path makes sense for the character. I also wanted to unpack a little bit the idea that there’s a right answer—that there’s an answer that’s the right thing to do and that there’s a decision that’s the bad thing to do. One path leads to empowerment and the other leads to complicity. I wanted to show the ways that both are flawed and complicated and fraught and that life rarely has a fork in the road where one is clearly the thing to do. Most of the time we’re given these two unideal options and you have to make a really complicated game-time decision without any perspective or understanding of how it’s going to play out. Preserving that ambiguity is important to me. It’s been interesting to hear from different people about what they think the narrator decided. There are a lot of different opinions.

I think you were completely successful at that because I had no idea which way she was going to go.

I can’t count the number of friends and readers who’ve read it and messaged me saying, “But what did she do?” And that’s the only question they have.

Since this is your debut, what do you hope this book says about you as a writer and what can we expect more of from you in the future?

I think a lot of the themes I explore in NSFW are themes I’m still interested in. I’m interested in voice-driven fiction and fiction that lives in the place where humor meets pain, where things are funny until they’re not. That is what I write without even intending to. I continue to be interested in morally gray subject matter and the dark messy parts of ourselves that we often keep covered up and hidden. I’m interested in digging deep into that and showing the intimacy and the vulnerability and the complicated hypocritical parts of ourselves that make us human. I’m interested in the relationship between women and the ways they relate to each other in different aspects of life. So, I imagine all that will continue being in my work but, as we’ve established, I can’t plan anything, I can’t outline, everything just comes as it comes. So, I will be just as surprised as everyone else for what comes next.

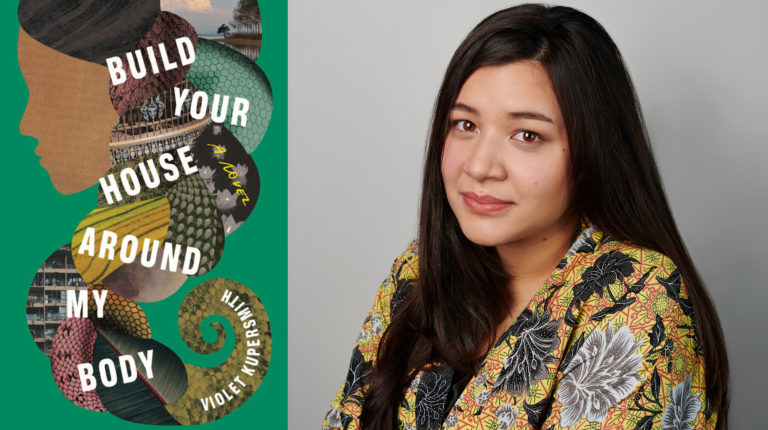

Featured Book

-

.

NSFW

By Isabel Kaplan

Published by Macmillan / Henry Holt and Company

From the outside, the unnamed protagonist in NSFW appears to be the vision of success. She has landed an entry-level position at a leading TV network that thousands of college grads would kill for. And sure, she has much to learn. The daughter of a prominent feminist attorney, she grew up outside the industry. But she’s resourceful and hardworking. What could go wrong?

At first, the high adrenaline work environment motivates her. Yet as she climbs the ranks, she confronts the reality of creating change from the inside. Her points only get attention when echoed by male colleagues; she hears whispers of abuse and sexual misconduct. Her mother says to keep her head down until she’s the one in charge—a scenario that seems idealistic at best, morally questionable at worst. When her personal and professional lives collide, threatening both the network and her future, she must decide what to protect: the career she’s given everything for or the empowered woman she claims to be.

Fusing page-turning prose with dark humor and riveting commentary on the truths of starting out professionally, Isabel Kaplan’s NSFW is an unflinching exploration of the gray area between empowerment and complicity. The result is a stunning portrait of what success costs in today’s patriarchal world, asking us: Is it ever worth it?

About Isabel Kaplan

-

Isabel Kaplan

Isabel Kaplan

Isabel Kaplan graduated from Harvard and holds an MFA in creative writing from NYU. She is the author of the national bestselling young adult novel Hancock Park and was born and raised in Los Angeles.

Photo Credit: Annabel Graham