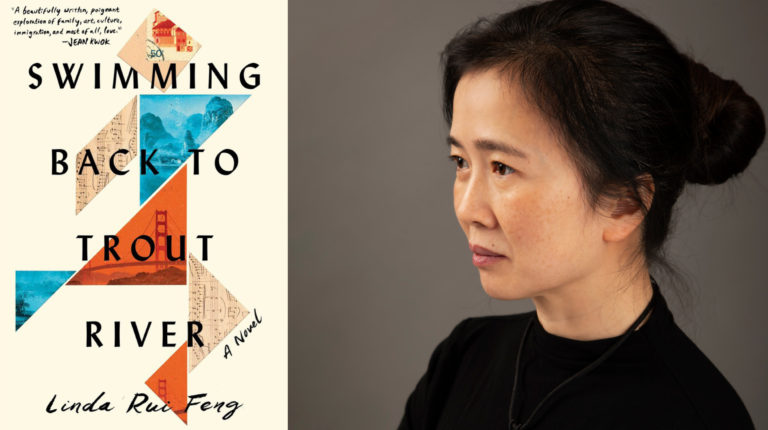

Adina Applebaum, Development Manager, interviewed Jackie Polzin, author of Brood, in celebration of being shortlisted for the 2021 First Novel Prize. In Brood, a woman valiantly tries to keep a small brood of chickens alive over the course of a year while facing brutal environmental challenges and her own struggles overcoming a heartbreaking miscarriage.

What was the first kernel of the idea for this book? What couldn’t you stop thinking about that led to creating this story?

A lot of the story is rooted in a true experience— my experience raising chickens and my experience struggling to get pregnant and have a child. Those two things happening in my life consumed my mind. It was a whole way of viewing the world, to have these animals I was responsible for who were really fragile, and to want something that seemed impossible. I was able to seek refuge in the chickens, and I thought of them differently given my worldview at the time. I had also been reading Karl Ove Knausgård’s My Struggle, the first volume, and I really loved the way it delved into minutiae or mundane aspects of everyday life. His books are rooted in gritty struggle, but they’re also about everyday living, and I felt that was permission-giving, in a sense, to embrace the stuff of daily life.

That was one of the things I loved about the book, was the way you really give dignity to those little moments of everyday life, both for the humans and the chickens.

I love that word. I don’t think anyone has used that word, dignity, but I wish I had written that on a piece of paper as I was writing. Not underestimating or discounting the importance of small things in our lives is very important to me.

What were your biggest challenges with writing this book?

I’m a very slow writer, so the biggest challenge was the limitation of time, and overcoming that psychological resistance to writing slowly. I began the project right when I was starting grad school at Boise State. I secretly worked on it for the first year of grad school, then I got pregnant, and I was pregnant in grad school trying to make everything work. Thankfully I have a very supportive partner, which has been critical throughout. Then my third year in the program I returned to the project after having set it aside, determined to have it as my thesis. But then—I forget what the law of physics is, but it’s something like whatever you’re working on will expand to fit the amount of time you have to work on it—even with the thesis being a very important deadline for me, the work wasn’t done by the time I finished school. So yeah, time is always my obstacle. I was wondering, will I ever pick it up again and continue working on it? The writer Joy Williams was my mentor at Boise State and she said to me, “I want to see it when you’re done, send it back to me.” That generosity blew my mind. So then I had a reason to keep going and I had a reason to not wait. I didn’t want Joy to know I wasn’t working on it.

If Joy Williams was waiting for something from me, even if it took the rest of my life, I would feel that I had to do it.

There was a part of me that was so scared to send this to Joy that I thought I might just work on it forever. But knowing that I had her support was amazingly powerful to me.

How long did you end up working on the book?

It sold somewhere around the six-year mark. I wish I could tabulate the hours because six years is such a daunting span of time and yet I set it aside twice—once for almost a year and the other for probably 8 months—so it feels misleading to say six years.

I think it’s inspiring for other people because you didn’t give up on it and you allowed yourself to step away from it and come back. So much happened for you during those six years, including getting pregnant. I’m curious, when you came back to it after those breaks, did you find that your writing style or plot or approach was affected by those changes?

Absolutely. It was clarifying for me to set it aside for chunks of time. I think being attached to the work is really tricky for writers, and it’s amazing how much my attachment fell away in the time when I was apart from it. It allowed me to feel confident to get rid of things that weren’t serving the book, and I had a moment where I realized what has to happen for the novel to progress, which I don’t think would’ve happened the same way if I didn’t have that time.

Also, something that motivated the writing of this book was thinking I wouldn’t be able to have kids, which is something I always thought kind of blindly would happen for me, and I wanted to know what it felt like to mother something. I was exploring some other way of caring for something, both with raising chickens and with writing this book, neither of which really return that love in a formal sense. I wanted to explore a connection like that, and how that prolonged act of care changes somebody. Then I did end up having kids. I was able to then put it through this filter— how much is this experience the narrator has like the experience I’ve now recently had of having a baby? I was surprised that there were a lot of similarities and analogies that held true.

What was your writing practice like?

When I began writing this book I was working in a restaurant. I would typically work the night shift and then I would try to wake up, eat something, get some exercise, and write. I know that sounds like I was very disciplined, but no. I would put the writing off, or I would push the exercise back because I wanted to write. These are all things that aren’t necessarily easy to initiate so I would waste tons and tons of time, but most days I sat down to write at some point. Any day there’s time to write, I sit down and do it, usually for not as long as I think I should. I’ve become more and more disciplined the less time I have to write. I just started taking this course called Writing for Night Owls because I’m trying to reclaim the night. I used to be a night owl and as soon as I went to grad school I became less of a night owl because I had early responsibilities. So, I’m trying to retrain myself to have the night as another possibility to write. Not because I’m someone who thinks you have to work every hour of the day, but because I’m trying to be more playful about it. I write from 10:00 p.m. to midnight on Thursday nights. It’s fun.

I think I read Karen Russell talking about her writing process somewhere that has a similar idea. If I even touch the work in the evening, I wake up in the morning and I’m not scared of it. There is fear in my process. If I can wake up having made friends with the work the night before and I’m still friends with the work it’s like I might not ever have to be afraid of the work again. I’m okay with acknowledging part of my process is rooted in resistance and I need to work with it.

What are some larger conversations or topics that your book speaks to or engages with?

I think the book speaks to the unspoken. Miscarriage is a subject of silence. It’s something that is happening all the time and yet you tend not to hear of it happening unless it’s in your own family, maybe, or your closest friends. There’s a disproportionate amount of silence as compared to the amount of human experience that’s taken up by this intense natural thing that yields a lot of suffering. When I experienced it, it felt like silence was the rule and I felt so angered by that, so part of my motivation is just putting something out into the world that combats the quiet surrounding it.

Your book also makes space for the complexity of the grief and the emotions surrounding a miscarriage as well. It’s not a straightforward narrative of a miscarriage, it’s much more focused, to go back to the dignity of the book, on those more quiet moments and prolonged grief, rather than the immediate grief of the experience.

Thank you. And it’s true that grief is so ongoing. Our culture is so focused on, “When will I heal, when will I get through this, when will I forget?” There’s this book I read recently called Flesh & Blood by N. West Moss which is a true story about a bodily illness that prevents her from having kids, and she writes so well about that cyclical nature of grief. There’s that unpredictable nature of loss.

Since this is your debut as a novelist, what do you hope this book says about you as a writer? What can we expect more of from you in the future?

In the course of those six years spent writing Brood, I did begin two other projects that I can see myself working on for a while. In the last trimester of my second pregnancy, I was working away on this other project that I was super excited about, but—this was probably a nesting instinct—I decided to clean out my desktop and dumped everything in the trash and emptied it, and I realized I never saved the project anywhere else. I spent an hour summarizing everything I thought I said—it was like 60 pages of work—but I didn’t like the idea of that because I felt it ruined all the freshness. So then I set that aside, I had a baby, and eventually when I started writing again it was to finish Brood, but I never got that project out of my head. I’m thinking I need to finish the thing I’m scared to finish.

When I’m thinking about themes, though, you know, I mentioned that I wrote Brood because I wanted to write into the silence of this subject and carve out some of that space, but I’ve realized that I also felt a shame surrounding my experience with infertility. That shame feeds into the silence and was quite possibly some aspect of what motivated me to write the book. Now I think about the themes of the other projects I was working on and I realize there’s a thread of shame running through all of them too. The shame also runs alongside anger. You might read Brood and think, “What an angry book.” There’s a sense of injustice when your body can’t do something that you think it should. I don’t like saying that. I’d like to be motivated by just joy.

You have an unnamed narrator and the miscarriage happens before the book starts, even though it’s so central to the narrative. I was interested in your decision of how to decide what to include and not include in the book?

Both of those decisions felt very natural to me. When you’re writing in first person there are only so many instances when the name of the character comes about, but as a more deliberate decision, it ties into how the experience of infertility feels like it hinges on this question of identity. Will I be a mother? Who will I be if I can’t be a mother? And certainly the book is toying with the idea of being a mother can be different than just this one thing, but that idea of coming up against this wall, identity-wise, felt like a reason to omit the name. The internal journey of the narrator is towards the knowing of the self, and wanting to be known.

As I was reading I was really attuned to how many descriptions of gross food you had in the book—with the salad at the friend’s house with the cold shrimp, and especially when she’s at her mother’s house and she’s been simmering this soup all day but it’s really unappealing. Usually when food is included in a book in this vivid way it’s to describe a delicious or nostalgic meal. Could you talk a bit about the way in which you depicted food in the book?

That’s such a nice insight, no one’s ever mentioned that. I have a long history in being interested in baking, cooking, serving food and have been totally inspired by many chefs in my life, so it’s really funny to me to think about how I used food to reflect the discomfort the character was feeling in those scenes. It’s an amazing gesture of hospitality to be so uncomfortable and so unskilled with making food, and yet still trying to make someone feel welcome. I have a very emotional reaction to that, to the gesture of doing something you’re not comfortable with as an act of contribution or a bonding experience.

That reminds me of the scene where the narrator realizes she’s supposed to have been sterilizing the water for her chickens all along. There are ways that you mess up when you are trying to perform acts of care, but so much of what actually matters when you’re portraying care or mothering maybe is just the desire to do so.

Yeah, I think that’s completely true. They’re trying to care for others but coming up against their own limitations for doing so. I remember when a friend of mine had a child years before I did and I asked her, “How do you even know what to do next?” And she said, “Well, somebody told me if the thing you do is born out of love it will be okay.” That is a wonderful thought, but it won’t get you through everything.

Of course, I have to ask you about the chickens. Obviously I love the chickens, and they had such amazing names. Every time Darkness appeared I was just laughing, there were so many instances where “Darkness” being capitalized really adds a lot to the narrative. They also have such strong individual personalities. Do you have a particular affection for a chicken out of the four or did you love them all equally?

Over the course of owning chickens, my partner and I had 8 different chickens, so each of the chickens in the book is modeled after a specific chicken in my mind. Gloria has a special place in my heart, but something about the writing of Darkness really endeared me to her. Gam Gam was modeled after my favorite chicken, but I think that is less prominent in the story. It’s funny because when I’m thinking about the chickens in the book and the chickens they’re modeled after in real life, their personalities and their colors will go back and forth between the two when I picture them. It’s maybe like dreaming in a different language, when you take a character from real life and turn them into fiction and now you’re living in the fiction.

Brood was published by Picador in the U.K. and they made a woodblock print of each chicken and they made these postcards where they gave qualities and personality characteristics for each chicken. I’m going to send you a Darkness one.

Featured Book

-

.

Brood

By Jackie Polzin

Published by Penguin Random House / Doubleday

Over the course of a year, a woman valiantly tries to keep a small brood of chickens alive while facing brutal environmental challenges and her own struggles overcoming a heartbreaking miscarriage. This brilliantly insightful meditation on life and longing rewards its readers with the richness of reflection and unrelenting hope.

About Jackie Polzin

-

Jackie Polzin

Jackie Polzin

Jackie Polzin lives in St. Paul, Minnesota with her husband and children. Brood is her first novel.

Photo Credit: Travis Olson