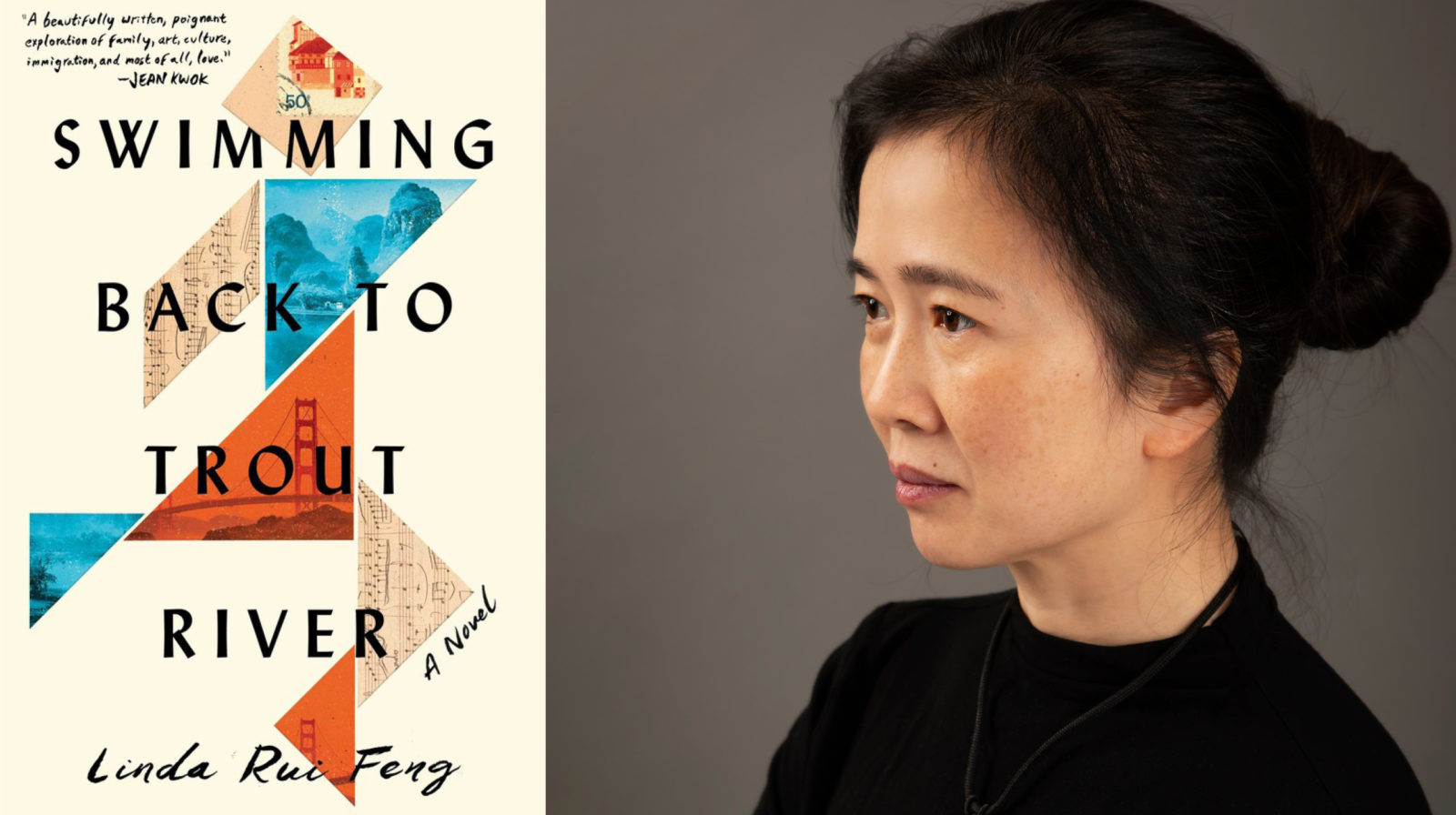

Amanda Braitman, Administrative Assistant, interviewed Linda Rui Feng, author of Swimming Back to Trout River, in celebration of being shortlisted for the 2021 First Novel Prize. Set against the backdrop of China’s Cultural Revolution, Swimming Back to Trout River weaves together the stories of Momo, who’s striving to bring his daughter to America by her twelfth birthday; Junie, who’s determined to stay in the idyllic countryside of China with her grandparents; and Cassia, who’s finally beginning to wrestle with a shocking act of brutality from her past after separating from Momo. This lyrical novel tenderly reveals the hope, compromises, and abiding ingenuity that make up the lives of immigrants.

What was the first kernel of the idea for this book? What couldn’t you stop thinking about that led to creating this story?

That’s a great question, and of course there are multiple kernels. Many years ago, when I was a science student as an undergrad, I was working at a science lab and I got to talking about Americans’ relentless pursuit of motion with the person who was supervising me. I can say that was probably the first time I thought about this pursuit of motion. Then, I had been thinking intermittently about this idea of roots and wanting to stay put in the place that we grew up or feel most at home. I started thinking about the tension between that pursuit of motion, what I would call an escaped velocity, versus that equally powerful urge to stay put. Of course, it’s complicated, the “roots versus rainbow” conundrum—the thing over the rainbow, the many things that draw you away from where you are from, versus what brings you back or allows you to dig in your heels and fight for the place that you are most familiar with. So, that narrative to leave and the counter-narrative to stay is something that has been preoccupying me for quite some time. Even before I thought that I could write fiction, or even that there was a novel anywhere in my brain, I think that was something that has always fascinated me. The idea that Junie was that counter-narrative to Momo’s urge to look for something elsewhere, to have that escaped velocity, probably coalesced into the first couple chapters of the novel.

That definitely makes sense and comes through clearly in the novel. I think you do such a great job of touching on those emotions and thoughts without outright saying the terms you just used and it comes out so beautifully and subtly.

Thank you, and I think in my particular experience the people who leave have other options, where this is not the case for refugees or those fleeing famine or war or other kinds of threats to safety. But in Momo’s case, there was a choice and the advantages and disadvantages of leaving kind of sneaks up on him over the course of his life.

I’m curious, what kind of science did you study? There’s some mention of physics in the book.

As an undergrad, I studied environmental geoscience. I was quite committed to being a scientist for a long time. I was just thinking about Peter Ho Davies’s wonderful event about revision; it really spoke to me about dealing with failure on one scale or another. If you think about it, failure is productive because it gives you something to work on and gives you powerful guidance of what to do next. The revision process is about getting to the next step. Even though my experience was quite limited, I still think about the ways that thinking about science and living with science has been productive and inspiring to me. Science has really made me appreciate larger scale problems. I did a lot of geology as an undergrad. We talked about time scales of millions and billions of years. Compared to that, a human life is very insignificant. I find that artistically very empowering.

What were your biggest challenges with writing this book?

There are lots of answers to this. I’ll say that one of the most tricky parts of making this story work was that I chose not to tell the story in chronological order. It was important to me that I tell it in an order that has its own logic. This is to say that it reflects the nonlinear repercussions people and places have on our psyche, and how we live our lives in a very forward manner but we often make sense and remember our lives in a very nonlinear way. I wanted a storytelling format that would reflect that messy process of remembering and experiencing. I really like the idea of telling a story that is distinct from how we live our lives, and our parents’ lives, and our grandparents’ lives. None of us have the luxury of actually experiencing our lives because we are not able to pinpoint those moments while we are in them. As a narrator, I have the power to identify moments of particular consequence in a way that is extremely satisfying for me. But, when writing in nonchronological order, it’s very difficult to keep the timelines in place and not confuse myself in the process. That was one of the top challenges.

Another challenge for me was to overcome this fear of not getting it right about the larger historical forces playing out around these characters. The larger Cultural Revolution for me is something that is momentous, complicated, and really difficult to do right. It was a challenge to outrun my own doubts of whether or not I can pull it off.

Something you did so powerfully was describing the texture of memories and how they influence our present and future. It may have been a challenge but you overcame it.

The texture of memories is really so interesting. I can go on and on about how to do that or why it’s so important to do that. I think the novelist Garth Greenwell said that he liked to write to capture what thinking feels like. It’s a wonderful challenge to capture what remembering and contextualizing and thinking feels like, and that was something that was always very important to me.

What was your writing practice like?

Well, in a word, it was messy. This was my first novel and I had no idea how to begin and how to continue, let alone how to finish it. I didn’t really have a ritual or daily routine. For most of the time I was writing it I was also trying to publish in my academic career, so I had all sorts of deadlines that were structured and very forward-moving. So my writing practice for fiction was interstitial. It was catching time as I could. I was also learning as I went along. Maybe the best way to describe it was as an improvisation on many levels. I keep wishing that the next time it will be easier, but everyone keeps telling me it will not. So I think I will continue to improvise in this way.

What are some larger conversations or topics that your book speaks to or engages with?

We already mentioned this idea of making sense of ourselves and this narrative of immigration and emigration, of leaving and staying. I think also one thing I hope to engage readers in with the book is the idea of a family being extremely malleable and not being bordered as a nuclear family, and the definition of the extended family really shapes who we are. Of course, it’s also about the textures of life in a particular time. When I was pitching the novel, my elevator pitch was that this book was about music, migration, and Mao. I thought the three M’s would capture it. But these days I was thinking how lucky I would be for readers just to resonate with walking in the shoes of my characters, and to feel as they feel, and to remember as they do, and to think about how we make sense of our childhood, and how we make sense of our geographies and our mobility across the world. I have become less and less ambitious about the larger themes that I had been trying to advocate with the novel. The texture of memory, like you said so beautifully, is what I’m most drawn to.

Since this is your debut as a novelist, what do you hope this book says about you as a writer? What can we expect more of from you in the future?

This is definitely a tough question. You’re asking me to predict the future a bit. I love messy stories — stories and situations and forces that are just beyond my grasp. Those are a little bit larger than what I can reasonably have a handle on at one time. By that, I don’t mean it has to be epic length. I really love stories where I go all out and reach the limits of my power; stories that are not easy to categorize or summarize, or the loose ends are not tied as neatly as they can be. I love reading those stories and like writing them. So hopefully I’ll get readers who like to read more of those.

I feel like those are often the most human. What life or life event has a tidy ending?

Right, I like stories that, instead of closing a door, opens another door or another portal. I hope that readers of this book will try to think of it as a door ajar. They could imagine the characters beyond the end of the book. That’s not to say that I will know what the end will be for those characters but I like having that option.

Could you speak to the relationship between art, which in the case of this novel is music, utility, and the cultural history of China in your novel?

That’s a huge question. I’ll try to narrow it down a bit. I’ll talk about the cultural history of China first. In my work as an academic, what I deal with most frequently are texts and artifacts that are thousands of years old. We are talking about 8th and 9th-century texts or objects. What is really interesting for me as a historian of that period is to see how much Chinese history is about the migration of people, objects, and ideas. At the same time, it’s also about how much people talk about how to police those ideas, people, and objects. Then move to 20th-century Chinese history, this was also going on. Of course, the Cultural Revolution was a very dramatic example. The idea of assimilating other kinds of influences such as music, classical western music, was at the heart of many of its stated goals. I was interested in looking at not just music, but the music at that particular time, when the influence of western classical music was playing out at different levels in terms of characters.

When Dawn and Momo have their argument about what it means to be useful to society by being an engineer, architect, or musician, what we are looking at is not necessarily a conversation about utility, but more a conversation about ambition and how targeted their ambition is. It’s also a view from a larger perspective about how much to police the movement of ideas and to police ourselves and our emotions and passions. Momo, at that point, is almost hesitant to give in to how music was changing him. And, of course, this change is reconsidered later on. I was interested in how youth and ambition can come into conflict with art and passion in that particular social context.

I have to ask, because I am from San Francisco and the scenes just brought me back there in a wonderful, bittersweet way, California and San Francisco specifically carry hefty mythology. What do these places represent to your characters, and, if I may ask, to you?

Before I answer that question, which scenes were you thinking about?

I think specifically I was thinking about Cassia or Dawn, they’re staying with friends and they are walking around the garden in the fog. The fog is so powerful to me. It’s a unique feature of the city. I remember walking to the bus stop and not being able to see 5 feet in front of me, and that’s a very distinct feeling. It’s just completely surreal. Also, your descriptions of the Pacific Ocean, and all the different colors of the Pacific you describe that I miss.

It’s really interesting to hear that. I didn’t mean to turn the question around, I’m curious how people have spatially-inflicted memories. I like the way you used the word “mythology.” I’ll answer one part at a time.

First, what does San Francisco represent to my characters? In Chinese, the name San Francisco is “old gold mountain,” a reference to the gold rush days. Immediately if you think about it deeply enough you come against that history. The characters don’t have to be steeped in the California gold rush history to really participate in that. I love the idea that San Francisco for Cassia and Momo are gold mountains, are prospects of gold in whatever form. It’s something that calls to them.

I also love that you mentioned the ocean. As a place, as an American city, it has a very particular view of the ocean. It’s not a holiday-maker view, but it’s not a brutal view of the ocean like the Northeast coast in the middle of winter. It has a lot of room for imagination. You can imagine it as a port or see it as a bridge to something, or it can be at the end of a portal. The history may or may not be visible in the characters, but the ecology of that is extremely visible. The characters are steeped in those possibilities. I remember a line from Jennifer Egan’s A Visit From the Goon Squad. She’s describing a high school in San Francisco, it’s a place where the ocean is always over your shoulder, and I really love that idea that you could just never be far away from a reminder of what might be out there across the ocean, or how we’ve come across the ocean.

This idea of fog that you mentioned, I love exploring the idea that our physical surroundings and weather can shape how courageous we are and can change whether we are able to face something or not, whether it’s our relationships or deepest fears or desires. So when I wrote about Cassia in the garden encountering fog for the first time, it’s both liberating and bewildering. I love the idea that fog is able to hide but at the same time reveal. That scene is a wonderfully pleasurable scene to create because I think about the kind of transformation that fog can actually afford us as human beings. I also love the fog a lot. For me, San Francisco is very near and dear to my heart. I went to high school in San Francisco. And while four years isn’t a long time, before that I had moved all over China and to many parts of the U.S. Up until then, I had never been in a school for more than two years at a time. It was really the first time I had been in a school and lived in a city long enough to really appreciate the seasons and in high school, we come of age in certain ways. I went to a public high school. I had wonderful teachers in the sciences and humanities. I still think about them. It’s a place where I was given a lot more than I could ever really repay. I’m the recipient of different kinds of generosity. That feeling of gratitude is a gift. I can tap into it. It’s very nourishing. I keep thinking about stories that can be set in San Francisco and on the edge of water and landforms where the sea can be a barrier but also not. That’s something that has really informed what I have done with my fiction.

The last scene set in California is so indicative of what you said. It’s an ending and a beginning. Do you have any information about the cover design? It focuses on San Francisco, but only subtly.

It was designed by David Litman, a really talented designer. Those triangular shapes are part of a puzzle game called Tangrams. This was a childhood game I was familiar with, and a lot of children growing up in China would be familiar with. It’s a sheet of plastic that is composed of different triangles and polygons that has limitless variations on how to arrange them. It reflects so much of the importance of childhood in the story, and the refractive part of the larger story that isn’t represented by just one character. The fact that you can retell the story, reshape the narrative— it’s a finite amount of shapes that can create an infinite number of shapes. I just really love that idea and design for all those reasons. I love the idea that we rearrange our own memories and own pasts as we cross borders and we confront our own experiences. We do that sleight of hand, or retroactively learn from our past, and it is something that I think is really powerful.

Featured Book

-

.

Swimming Back to Trout River

By Linda Rui Feng

Published by Simon & Schuster

Set against the backdrop of China’s Cultural Revolution, Swimming Back to Trout River weaves together the stories of Momo, who’s striving to bring his daughter to America by her twelfth birthday; Junie, who’s determined to stay in the idyllic countryside of China with her grandparents; and Cassia, who’s finally beginning to wrestle with a shocking act of brutality from her past after separating from Momo. This lyrical novel tenderly reveals the hope, compromises, and abiding ingenuity that make up the lives of immigrants.

About Linda Rui Feng

-

Linda Rui Feng

Linda Rui Feng

Born in Shanghai, Linda Rui Feng has lived in San Francisco, New York, and Toronto. She is a graduate of Harvard and Columbia Universities and is currently a professor of Chinese cultural history at the University of Toronto. She has been twice awarded a MacDowell Fellowship for her fiction, and her prose and poetry have appeared in journals such as the Fiddlehead, the Kenyon Review, Santa Monica Review, and Washington Square Review. Swimming Back to Trout River is her first novel.

Photo Credit: Anastasia Brauer