December 1, 2023

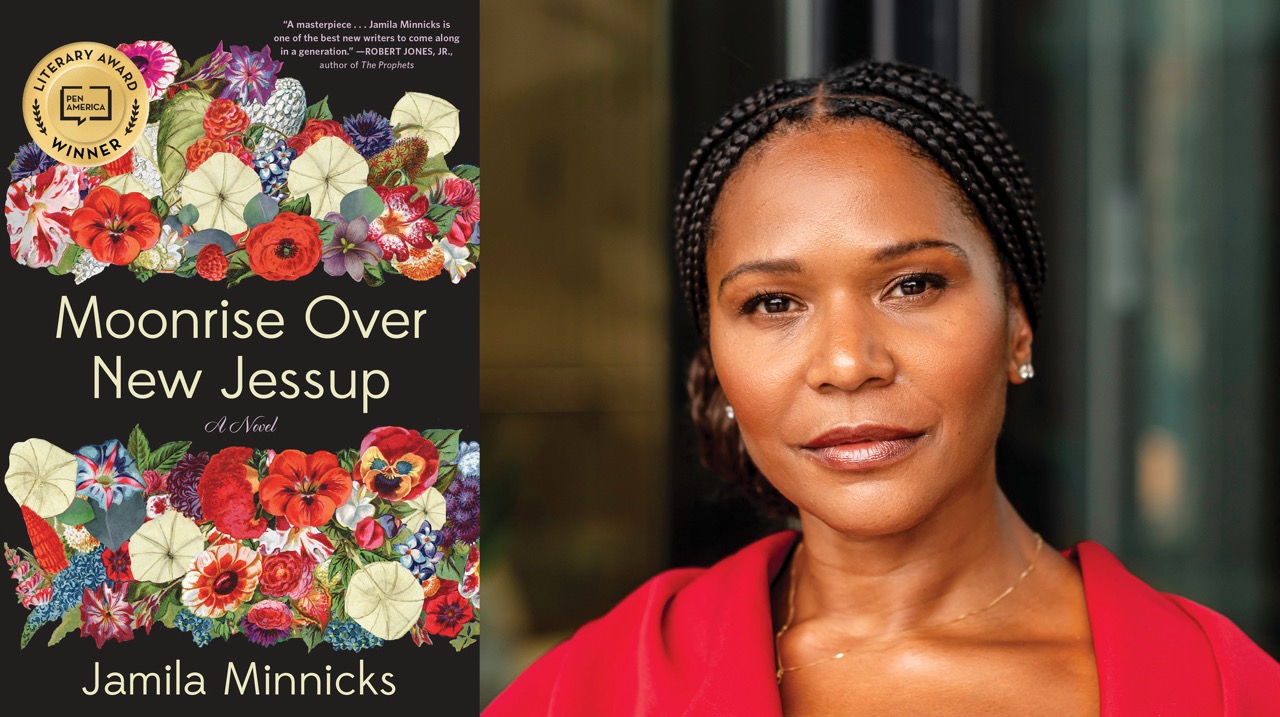

Jamila Minnicks, author of Moonrise Over New Jessup, spoke with Melanie McNair in celebration of being shortlisted for the 2023 First Novel Prize. The novel takes place in 1957, when Alice has just arrived in the all-Black town of New Jessup, Alabama, where residents have largely rejected integration as the means for Black social advancement. After she falls in love with Raymond, whose clandestine organizing activities challenge New Jessup’s status quo and threatens the couple’s place in the community, she must find a way to balance her support for his work with her desire to protect the town from upheaval.

Since you’re a lawyer by trade, how did you jump into becoming a writer? How long have you been writing fiction?

I started writing fiction when I was in high school, but I think it was just like every high school kid who likes to write short stories. This iteration of my fiction-writing career began in about 2019, when I started to write because I had questions about the world and I wanted to try to make sense of the things that were going on around me. I’ve always been a creative writing person—I’ve always been told I can’t be that creative in court, because it’s very technical writing— so, I needed an outlet for my creativity. I started writing short stories again, and participated in NaNoWriMo in 2019, and tried to make it a really organic practice, just to play in my creative space sometimes.

What was the first seed of the idea for this book?

In June of 2020, I thought about writing a short story about a Black family, like at Thanksgiving or something, arguing about the merit of Brown vs. the Board of Education in Alabama. My family’s from Alabama, and my family is full of educators and people who would have been directly impacted by Brown and the resulting desegregation of the schools and they, like many Black people, had opinions about that. They would talk particularly about enclaves like New Jessup, where people were not enjoying their economic rights and were having their votes disenfranchised, but they had also built these communities where they were thriving, relatively speaking. Their argument was let’s make this conversation about resources, let’s not play into these ideas about how proximity to white people will make their lives better, when all evidence pointed to the contrary.

I grew up hearing these stories my entire life, and I was very interested in seeing how that played out, and figuring out my thoughts on it and my understanding of what they were living through at the time. So, I thought I would try to write a short story about a Thanksgiving dinner, and it turned out to be much more than a Thanksgiving dinner. It was like looking at an old family photo—I could envision what everyone was saying, and then there was Alice and she’s holding this Thanksgiving turkey and she’s saying nothing, she’s hiding everything behind her smile. That’s how I knew it was her story, and that’s how I knew it was going to be a novel.

The language of the book feels like it’s of the era that the book is set in perfectly, and that is no small feat. Did you have to do research for that? Was it from talking to family members? Did you have early readers that helped?

My family’s from Alabama. I would say my family was Alabama before Alabama was a state. So growing up with that influence in my ear, I mean, Alice is all the women in my family. She’s a composite of my momma and my aunties and all the people who I came up with. And then getting the dialogue right, part of it was obviously just coming at things surrounded by loving family and community, but I also wanted to take the book home. I wanted to take the book to Alabama. It had won the PEN/Bellwether prize and it was about to be published and so I told my family, if you all don’t agree with this book––talk about early readers, I mean I think when people think about early readers they think about workshops. My workshop was my family, which is a huge gamble.

Probably a lot more of a tough crowd.

Well the thing is, if they didn’t like something they would say things, like, “Well, I bet there’s someone in Alabama that would talk like that.” So, you know, it comes from a place of love. My whole goal was I wanted them to recognize themselves in literature, because they read books by Alabamans, and there’s a frustration about the exploitation of Alabama and the Black experience of Alabama just being a single thing. So my thing was, I wanted to make sure that when they read this book, they could look at it and say this was our experience.

You mentioned the Bellwether prize. What was that experience like, to be selected by Barbara Kingslover?

It was pretty incredible, I’m not going to lie. I was not expecting it. I wrote this book thinking I was going to self-publish it, and I was going to ride it around Alabama with my family saying, “Hey y’all, I wrote a book. There’s fictional anecdotes in it, the names don’t match the people but there are family names in it.” So, when the opportunity for the Bellwether popped up on Submittable, I debated the merits of throwing my hat in the ring. Other people say, closed mouths don’t get fed, right? My thing is, I’m just going to toss. I submitted it and then I didn’t forget about it. Every day I manifested it, because every day I saw my book and believed it was special. Every day I thought, New Jessup is going to win the Bellwether prize.

Then, at first I got an email saying I was shortlisted, and then I got a text message saying, “I’m looking for Jamila Minnicks. This is about the Bellwether, is this a good time?” I picked up the phone and she was like, “Is this Jamila?” You know, she’s got this really smooth voice, and I was like, “Yes.” She said, “This is Barbara Kingslover.” And I said, “This is not Barbara Kingslover, this is my friends pranking me.” And she said, “I can assure you this is Barbara Kingslover.” It was such an incredible phone call because I could tell not only that she read the book, but that she had engaged with the book, even at that early level. She had some incredible feedback, including—the original title was Hydrangeas Over New Jessup—and she was like, “No, you gotta get rid of that title.”

But it’s so Southern!

It is but she was like, it’s just too soft, it doesn’t really give you a sense of movement and what Alice is really doing. But she also said, which always sticks with me, she said, “I never would have had the imagination to write this book.” This is Barbara Kingslover saying that! So I was like, “Well that’s an interesting thing to say, why?” And she said, “Because in all my life, I have been taught that proximity to white people is what made Black people’s lives better. So I never had the imagination, if you will, to think that there are whole communities that just didn’t believe that integration was the way to Black empowerment.” And for me, it’s sort of the worst-kept secret in my community, and so it surprised me for her to say that, but I really appreciated that she said it, because she’s Barbara Kingslover!

That brings to mind a couple of things. We did an NEA Big Read of Ernest Gaines’ book, A Lesson Before Dying, a couple years ago, and I was reading an interview that somebody had done with him and they asked, “Who did you write this book for?” It’s set in Mississippi, it’s also a Jim Crow book, but a very different one. It’s more of the one we all are familiar with; somebody’s falsely accused of something and he’s executed. And he said, “I write for young African-American girls and boys so they can see their history reflected, but I also write for white Southerners, because if they don’t know our history, they don’t know their own history.” And I just think that’s so true; there’s some skewed versions about the history of this country, which has been changing. I feel like this season especially there are so many books that have come out that are set either at the time of Jim Crow in the South or in the North, to see what the contrast is and what happened to people who were part of the Great Migration, and what they found when they got to wherever they were going. Why is it important to tell these stories?

I agree that I write for Black people. I think it’s really important, when we are rendering our people on the pages, that my elders in particular are able to see themselves honestly. I mentioned that I was showing my book to people, and some of my elders were really hesitant to even engage with the work because they had an expectation that certain traumas would be exploited. We’re talking about Alabamans in the 1940s, ‘50s, and ‘60s. We all know the stories that are so commonly told, and so some folks were like, “How many police dogs are in the book?” Before they even opened it. And that’s a fair question to me because I think that when we talk about my ancestors and elders, if they feel like the only stories are these very marginalized stories, it’s fair for them to disengage with it, because they carry that trauma with them. So, why would I want to read a book that exploits my trauma when I still have it? I had talked to elders over the summer who were classmates with the girls and boys who were killed at the 16th street bombing. So, for me to write a book to then exploit that trauma, and then shove it in their face? It’s to re-traumatize them, because they’re still carrying that around.

So, I write for them, because they remember these communities. They remember the trauma, but they also remember the Church, they remember their school, they remember their neighbors, they remember the store keeper, they remember the people up the street, the man who gave them candy after they got A’s on a test. They remember community. And so, my job, I think, is to write that. We should capture the full breadth of these stories because otherwise, if we chip away the good parts of our histories, if we chip away the pieces of our history that are us as humans, and we just marginalize people, we really condense to just our trauma, then what are we saying? And what are we passing along to future generations?

I write Black freedom, and I think it’s important for us, when we have these conversations, to frame literature in a way that does this work. What does Black freedom look like? All of our experiences—learning to ride a bike, having a bad experience with a landlord as Alice did, finding New Jessup, having envy, having enemies, falling in love—all of those things inform what I’m going to say freedom looks like, what Alice thinks freedom looks like, what my elders, what my ancestors, thought freedom looked like. I write because I want to capture, as best I can, their ideas of freedom, and I also write because I want future generations to think of this, and to really spark their imagination as to what freedom looks like to them. We throw this word around, right, but if you sat down and really thought about what that meant for you, for your household, for your community, could you really say? Other than these huge esoteric things, could you really, concretely say what that looks like? So, I write to challenge, especially Black people, to figure out what that looks like, and that’s all informed by our experiences.

What were your biggest challenges in writing the book?

The first draft came really quickly. Then, I found out about the Bellwether, and I revised it within a few months. I was just writing. I didn’t come from the MFA tradition or the writerly community, and I guess I hadn’t enveloped all of the anxiety. I just thought, I’m going to write something that feels true. You know, it’s hard to say, because I really enjoyed the process of writing. If anything I would say it’s hard to figure out the right time of day. I was working as an attorney, and it was Covid, so I started work at 7:30 or 8 o’clock in the morning. I had a lot of responsibility, and it was hard for me to figure out what time of day my brain would be most creative and most able to be in tune with Alice. So, when I woke up even earlier to write I was finding myself running up against the clock because I still had to get my day going. I started at 5:00 a.m. and I just didn’t have enough time. Then I moved to 4 o’clock; felt good, but it still wasn’t enough time. So it took a little while to calibrate because I feel like at 4, I’m still in a liminal space where I can capture language the best and things just flow. But at 3 o’clock I was still too cloudy. So, not having enough time, that’s a difficult thing that we all run into, I think.

And are you a daily writer?

Yeah, I mean, I have to. With the new piece I’m working on, I’m in a zone, the same sort of zone I was in with New Jessup. I’m not somebody that feels like their ideas escape me, but I feel like they pile up. I don’t want to lose that momentum, so yeah, I have to write every day.

That’s really impressive. I feel like there are thousands of MFA students who are wishing they have the work ethic you have.

I don’t know, I’ve heard that before but I don’t know if it’s work ethic. I just feel responsible for giving these stories to the world. I could live a thousand lifetimes and only tell a little drop in the entire ocean of stories that there are to be told. So, I feel obligated to do the work. You know, it’s important to me to tell these stories. Every time even one of my aunties or someone in my family reads a little short fiction piece––just to see the smile and hearing how it brings a memory to their mind that they want to share with me. That feels so crucial, the filling in, the coloring of lines that I can color.

So it’s this calling?

That’s how I feel. That’s how I really feel.

That’s really beautiful. Who are some of your favorite Black Southern writers?

Jesmyn Ward and Kiese Laymon, Maurice Carlos Ruffin, and I count Deesha Philyaw, because she grew up in Florida, and I consider her to be a Southern writer, and her stories are also very Southern. Those four really showed me so much about craft and so much about how to embrace all the things you love about the South in literature. They’re incredible. It just feels like such an incredible energy propelling Southern stories forward, and that is really inspiring to see so many Black writers embracing this calling to write about the South. I want more people writing about Alabama but, you know, we’re getting there.

Ayana Mathis just wrote something about it.

Yeah, she did! I haven’t read it yet but I’m also excited to read James by Percival Everett. That’s turning a narrative on its ear and saying, okay, you all called him Jim because he was a slave man, but I’m going to tell the story of James. To me, that’s really exciting, that’s really brilliant. Stuff like that is changing the entire game.

It’s interesting because Barbara Kingslover is also on a mission to get people to see the South in new ways. I think her audience is probably mostly white, I don’t know, but it’s the same project of turning stereotypes into a whole vision.

And that’s exactly right. I see so many people and how they talk about the South. I mentioned Alabama to a man when I was in Minneapolis this summer. He asked what my book was about and I said it was about a young Black woman in 1957 Alabama, and he cut me off, and he said, “Oh I hate Alabama.” I think he was assuming I was going to go a different way, but I said, “What is it you hate about it? Perhaps the weather? Is it too hot for you?” And he looked at me and he was like, “Well, no.” And I said, “Well, what is it that you dislike about Alabama?” And, you know, he’s this older white man, and he looks at me like I’m the one that’s being ridiculous. So I said, “Oh, is it the socio-political problems of the state?” And he said, “Well, yes.” And I said, “Okay but my family’s been in Alabama since the early 1800s. We hunted on that land, we fished those rivers. We grew food on that land and built businesses on that land, built houses on that land, built communities on that land. So the land isn’t the problem. So when you say you hate Alabama, what you’re saying is you hate the sins in the hearts of man that are damaging Alabama. But my people love Alabama. And that’s what I write about.”

It’s really interesting to me ––because he also admitted he had never even been to Alabama––that you have people who have these deeply held prejudices against places they have never been. So our job as writers is to introduce people to these places, so then if you maintain that prejudice despite all evidence and any book to the contrary, then we’re going to make you work to maintain that. Or, you’re going to have to completely ignore an entire canon of literature that’s seeking to tell you the truth about the diversity of thought, the diversity of experience, the diversity of geography, in the South.

Featured Book

-

.

Moonrise Over New Jessup

By Jamila Minnicks

Published by Hachette / Algonquin Books

It’s 1957 and Alice has just arrived in the all-Black town of New Jessup, Alabama, where residents have largely rejected integration as the means for Black social advancement. After she falls in love with Raymond, whose clandestine organizing activities challenge New Jessup’s status quo and threatens the couple’s place in the community, she must find a way to balance her support for his work with her desire to protect the town from upheaval.

About Jamila Minnicks

-

Jamila Minnicks

Jamila Minnicks

Jamila Minnicks is the author of Moonrise Over New Jessup, the 2021 winner of the PEN/Bellwether Prize for Socially Engaged Fiction. Her work is also published in CRAFT Literary Magazine, The Write Launch, and The Silent World in Her Vase. Her piece, Politics of Distraction, was nominated for the Pushcart Prize. She is a graduate of the University of Michigan, the Howard University School of Law, and Georgetown University. She lives in Washington, DC.

Photo Credit: Samia Minnicks