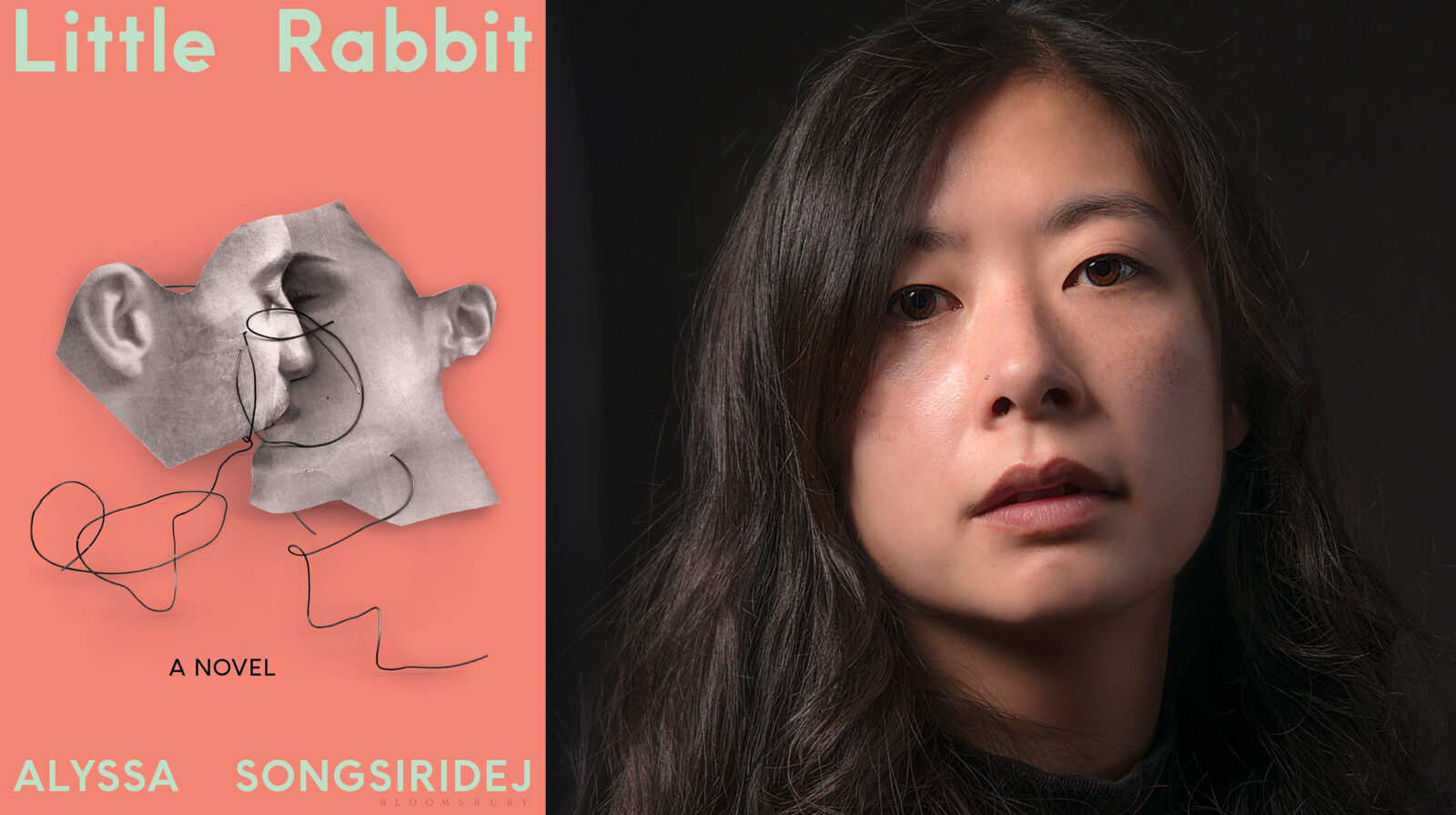

Alyssa Songsiridej, author of Little Rabbit, spoke with Ceara Hennessey, Barista at The Center’s Café & Bar, in celebration of being shortlisted for the 2022 First Novel Prize. A queer woman in the early stages of her writing career meets an older renowned male choreographer at a residency and begins a submissive relationship with him that confounds her social circle. The complicated sexual politics of their love story test the boundaries of lust, punishment, agency, and artistic drive in this darkly sensual take on a coming-of-age novel.

What was the first seed of this story?

There are a couple of seeds to the story. The first one is I was listening to this audiobook by the relationship therapist Esther Perel called Mating in Captivity, which is about sexuality and keeping desire alive. She had this short section about strong feminist women who realize they want to be dominated in bed and they’re sort of horrified by their own desires and trying to reconcile their political beliefs and how they present themselves in the world with this thing that they wanted and in their private lives. That was really interesting to me. I wanted to dive into the perspective of a woman who’s trying to negotiate this for herself, who’s trying to figure out how the public self she presents meshes and contradicts with this new private self that she’s discovering, and to take a relationship that’s presented often as a cliche and try to give it an empathic human life, purely from the point of view of the woman. I really wanted to focus on what she wanted and her desire and to depict female lust in literary fiction because I felt that was something that was missing from what I was reading.

The other seed was that I had gone to a residency and I overlapped with a choreographer who brought dancers with him, and I didn’t know anything about dance—I took, like, one ballet class when I was five and I was really bad at it—and so I’d never seen choreography being made up close. They did a performance for the other residents and I got to really see how the choreographer worked and I was completely fascinated. It’s just a completely different way of making art and it seemed so far from what I was doing and I was really envious. I was just hunched over my laptop and feeling alienated from my body, so to see these amazing artists making art with their bodies was amazing and I wanted to see how I could use writing to get as close to that as possible. Those two seeds were both such embodied ideas, so they seemed to really fit together in this narrative.

What were your biggest challenges when writing the book?

Part of it was bringing in the outside world because it’s such a tight first-person point of view. You don’t even know her name until the very end. So, trying to figure out that balance between her public self— what she could be losing, what’s at stake—as she pursues this relationship was the most difficult part and also the most emotionally wrenching part for me. I brought that in in the form of the roommate, Annie, the best friend that she’s known since college. Originally, in the first draft, I didn’t have that character, which always shocks people because it is such an integral part to the story. Then I had a friend who read the draft and was basically like, “Why doesn’t she have a female friend? What’s at stake, what’s she losing?” And then everything clicked and I realized she has this friend, she’s also her roommate, she’s also a writer, they’ve known each other forever, they’ve identified with each other in all of these intense ways. Getting that right really helped me get over the hurdles I was facing. I feel like in some ways that’s the core of the book, that relationship. It’s just as important as the romantic relationship. There’s a way that they mirror each other.

Yeah, the juxtaposition between them is so great, and it is really interesting that she wasn’t a part of the first draft. I feel like Annie adds so much to the narrative. What was your writing practice like?

My normal writing practice, my everyday writing practice, is much slower and rather torturous. Like the narrator, I do try to write some hours before I log into work, which is a little bit easier now working from home. I don’t have to wake up at 5, I wake up at 6:30, so I get a little bit more sleep. Sometimes it can really feel like a struggle, and sometimes it feels really great, but I try to put everything that I can into that time. I was doing that for a couple of years while I was working on a completely different book and I was writing short stories and I was getting in my own way because I thought I had to write an intellectual book about capitalism, I’m going to destroy traditional narrative, I’m going to be a brilliant genius, but really I was just making myself miserable and not really writing anything.

Then I had this idea to write this dancer relationship novel in the fall of 2019, but I couldn’t find time to do it because I was doing a bunch of freelance projects and just working a lot. Then in 2020, when the pandemic hit, all my work dried up so I had to go on unemployment for a few months and that gave me whole days to just focus on the book. I did this artist workshop through MASSMoCA that was trying to help artists figure out how to make a living and the person leading the workshop was like, look, if you can get government assistance, do it and focus on your work. You’re a really valuable part of the economy. So, that was really pivotal for giving myself permission to write in the way that I’d never really given myself permission before. I was able to get out of my own way and wrote the first draft by hand very quickly, in a few months. I also didn’t have a life because no one had a life, so that helped. That’s unusual for me, though. I’m never going to write another book in that way again, hopefully, and I can just go back to my two hours every day monastic practice.

It’s so interesting to talk to writers who worked on their book during the pandemic and seeing how they utilized that time because I know for some it was really beneficial like you were saying, and some just totally shut down. I think it’s really fascinating how much that life changed how we relate to our art.

I did also give myself permission to not write in the beginning. I was like, I’m going to just take the time to take care of myself and I’m not going to try to write King Lear, or whatever. I’m just going to keep myself from going nuts in my one-bedroom apartment with my partner and my cat. Taking pressure off myself in that way actually enabled me to write.

So much of Little Rabbit is about the relationships between artists—we have the narrator and the choreographer, the narrator and Annie, the narrator and her friends in New York from her MFA—and how they come together to support one another and also compete with one another. One of my favorite parts of the novel is that early on the narrator describes herself as emerging, a verb, and the choreographer is established, an action in the past tense. I wanted to know a little bit more about what interested you about these types of relationships, especially now that I know that Annie was not in the first draft, and what was appealing about the relationship dynamic in particular between an emerging artist and an established one?

I’m very interested in how we make a life where we’re also trying to make art in our world, because it’s not easy. There aren’t a ton of resources for it. That kind of scarcity can really bring people together; you really rely on your friends and your community as an emotional resource to help you keep going because sometimes it seems like what the heck is the point? My back hurts and I’m alone and I could be watching Love Island. Why am I doing this? Having people around you who understand the weird power of trying to do this every day is really meaningful and important, but it can also be really stressful and difficult because you could find yourself in a pressure cooker situation, and you could find yourself in conflict with people.

Also, just the way that life and art rub up against each other too is something that I’m interested in because, as a fiction writer, it’s unavoidable that our life seeps into our work, so it’s figuring out how to do that in a way that feels protective while also acknowledging that it’s inevitable. The material we work with resembles the world. I think it’s a little bit different if you’re an abstract painter, like if you make a painting about your marriage it’s not going to be legible clearly to other people as that. Fiction is particularly fraught in that way. I’m also really interested in the relationships between people who work in different mediums. I personally have gotten a lot out of relationships with people who are painters, who are musicians, who can do a different medium than I do. I find it really enriching to be around people who understand the creative pursuit and approach it in a different way and have different tools on hand. My most inspiring, most energetic relationships that I have come through that.

Then to go to the emerging versus established question, I think ambition and art is really interesting to me and how you negotiate ambition with yourself and with other people and not let it destroy you. I spent a lot of my twenties being anti-ambition, living in a punk house without adequate heat and being like, “This is the real life.” But then I realized I’d had a cold for six months and I was not very happy. Trying to negotiate what’s a harmful external focus on ambition versus a personal ambition and trying to take part in something bigger than yourself was a really important part of my life and I think an important part of many artists’ lives. I wanted to show a person who’s at the beginning of negotiating that relationship and someone who has had a lot more time to figure it out and deal with it. It also fed into the question of patronage that I wanted to work with, to try and talk about how you figure out how to make art when you also have to pay rent and you also have to pay your bills, how do you make art under capitalism, basically. Each artist answers that question differently for themselves. The choreographer is more established financially and prestige-wise but acknowledges the relationships he’s had have gotten him there, whereas Annie ensconces herself a bit more into the meritocratic fiction because she hasn’t had to make those negotiations the way the choreographer has.

I really liked that it felt like a coming-of-age story but about a thirty, thirty-one year old. Usually, those characters are twenty-four, twenty-five, so it was refreshing to read this kind of story from somebody who was older. I think people in their twenties think that they need to have it all figured out by thirty, I know I used to, so it’s good to see how that’s not true.

I’m glad you said that because I do feel in the art world there’s so much pressure to figure everything out when you’re young and to achieve everything and be a prodigy when you’re young. That’s not realistic in a lot of ways. I really didn’t figure out what I was, or that I was even interested in writing until I was thirty or thirty-one. I specifically remember when I was in grad school I had this teacher who said, “You’re going to graduate from this program and then it’s going to take you ten more years to figure out how to write.” I thought that was horrifying at the time, but he was completely 100% right! That’s how long it took and that’s okay. You can come of age at any age. You’re constantly revising yourself. I think a really big danger for artists and for people is to just get stuck in this idea of who you think you are, what kind of writer you think you are, what kind of person you think you are, and committing to that and refusing to be flexible about it even in the face that you are changing because change is inevitable.

One of the narrative threads I really liked later in the book was the utilization of each character’s different types of art to talk about each other. We have the choreographer choreographing the dance about the narrator. We have the narrator writing the story that could be about the choreographer, or it could be about Annie. We have Esme mentioning towards the end that Annie might be writing a story about the narrator. I find the use of real people in artists’ work to be a very intriguing topic, and I know it’s controversial. I wanted to know what drew you to writing about this, and do you have any hard and fast rules about it yourself?

It just makes sense that your life is going to reflect in your art, even in weird subconscious ways. With the choreographer and the narrator, I got to use their different mediums to talk about the body versus language, which was also really interesting to me. As a writer, you think “If I can describe something it makes it safe, I’m able to have a handle on it in some way.” Then what happens when your experience goes beyond language is where the choreographer’s world comes in; it’s the body that’s meeting the art. It’s impossible to get what that experience is like in words. I tried. I think it’s impossible, but I tried. His understanding of the world being expressed in bodies is something that the narrator finds frightening because she can’t get it into words. I wanted that tension to really be there.

In terms of the characters, the fiction writers trying to negotiate the life into art question felt true to me because as you said it’s a very controversial and very fraught topic. My partner is not in the literary world at all but when these questions about life and fiction explode on the internet they explode into his internet too because that’s how big they are to people. It makes sense because it’s alarming to see what you think of as your life suddenly in fiction because you thought it was only yours.

You mentioned the naming before and I did want to ask about that because neither the narrator nor the choreographer are named until the final page. What was behind the choice to do this?

It kind of goes back to what I was talking about with the private versus the public self. A lot of the drama of the book has to do with what’s happening internally with the narrator and how she’s understanding this private relationship and what this private relationship means for her public self, the self that has the name that she presents to the world. I didn’t want to have that name used until the end when that was resolved for her.

I admired how seamlessly you portrayed the passage of time in the novel as we move through a year of the narrator’s life. How did you go about creating this arc for their relationship, what made a year feel like the right length for the story?

It felt very intuitive to me. Their relationship really mimics the seasons in this way that I didn’t intend but made sense when I was done. They have this whole summer thing that’s light and exciting, but then when it starts getting darker they have to negotiate more. I was also thinking about the seasons a lot more than usual too because I was walking in the same circle over and over again and noticing how things were changing. A lot of the time also has to do with the place. I wanted it to feel set in a particular landscape that was changing. I wanted it to be an east coast novel; the way the seasons feel really different in New England reflected the way that they feel different in their relationship.

Now that I’m thinking back to the novel, their relationship does feel most fraught in the fall and the winter and then sort of revitalizes in the spring. That’s so brilliant.

Right, and the fall and the winter is when you have all this family stuff and you’re bringing all these outside people in and are negotiating a new stage.

Yeah, the cuffing season mentality where you want to be in a relationship during the holidays so you can get through the holidays and the new year. What are some larger topics or conversations that we haven’t covered yet do you feel your book speaks to or engages with?

One note that I wanted to make is that it was really important that she be a bisexual woman, and that she’s a bisexual woman in a relationship with a cis-gendered man. Having it being a straight-passing relationship brings things back to my questions of the private self versus the public self—what happens when you are queer but everyone’s reading you as straight? That tension is a big part of it too, which comes up with Annie in a flammable way.

Yeah, Annie’s visceral reaction to the narrator as if she’s rejecting her queerness was a really resonant part of the novel for me.

I’m glad you said that because that was a really important element for me. It’s such a painful experience. You rely so much on your community so to feel in conflict in such a way can be really difficult and painful, and I wanted to convey that in the book.

I think it was very well conveyed and very appreciated. My final question is, since this is your debut, what do you hope it says about you as a writer and what can we expect more of from you in the future?

There is a theme of embodied sensuality that I think I will always be really interested in, and that I hope to bring to my books even if they go in different directions. I hope that is something that people associate with me from now on.

Featured Book

-

.

Little Rabbit

By Alyssa Songsiridej

Published by Bloomsbury Publishing

When the unnamed narrator of Little Rabbit first meets the choreographer at an artists’ residency in Maine, it’s not a match. She finds him loud, conceited, domineering. He thinks her serious, guarded, always running away to write. But when he reappears in her life in Boston and invites her to his dance company’s performance, she’s compelled to attend. Their interaction at the show sets off a summer of expanding her own body’s boundaries: She follows the choreographer to his home in the Berkshires, to his apartment in New York, and into submission during sex. Her body learns to obediently follow his, and his desires quickly become inextricable from her pleasure. This must be happiness, right?

Back in Boston, her roommate Annie’s skepticism amplifies her own doubts about these heady weekend retreats. What does it mean for a queer young woman to partner with an older man, for a fledgling artist to partner with an established one? Is she following her own agency, or is she merely following him? Does falling in love mean eviscerating yourself?

Combining the sticky sexual politics of Luster with the dizzying, perceptive intimacy of Cleanness, Little Rabbit is a wholly new kind of coming-of-age story about lust, punishment, artistic drive, and desires that defy the hard-won boundaries of the self.

About Alyssa Songsiridej

-

Alyssa Songsiridej

Alyssa Songsiridej

Alyssa Songsiridej is an editor at Electric Literature. Her fiction has appeared in StoryQuarterly, the Indiana Review, the Offing, and Columbia: A Journal of Literature and Art, and has been supported by Yaddo, the Ucross Foundation, the Ragdale Foundation, the Vermont Studio Center, the VCCA and the Massachusetts Cultural Council. Little Rabbit is her first novel. A National Book Foundation 5 Under 35 Honoree, she lives in Philadelphia.

Photo Credit: Jaypix Belmer