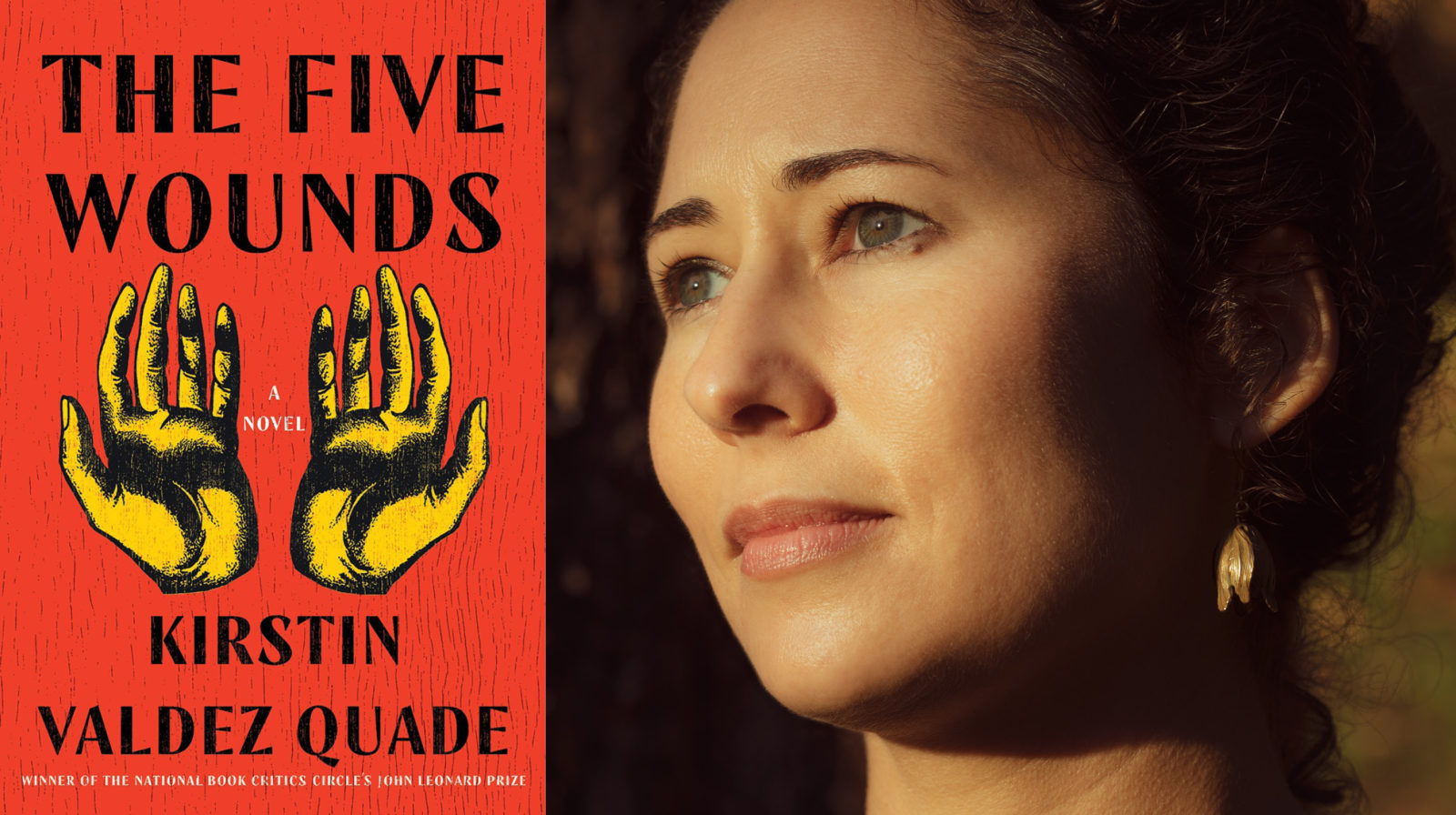

Eliana Cohen-Orth, Production Assistant, interviewed Kirstin Valdez-Quade, author of The Five Wounds, in celebration of being shortlisted for the 2021 First Novel Prize. In The Five Wounds, Amadeo Padilla was hoping for redemption through his portrayal of Jesus in the Good Friday procession of his small town in New Mexico when his fifteen-year-old daughter, Angel, shows up pregnant after fleeing her mother’s house. Five generations of the Padilla family converge during the baby’s first year, bringing to life their struggles to parent children they may not be equipped to save.

What was the first kernel of the idea for this book? What couldn’t you stop thinking about that led to creating this story?

The novel grew out of a short story. It was, for a long time, just a short story in my mind, and the very first kernel of inspiration happened when I was working as a grant writer for a nonprofit in Tucson. One of the organizations that we worked with ran a teen parent program. It was a GED and high school equivalency program for very young mothers. I went to do a site visit where I spent the day with these girls and their babies, and I was so struck by their earnestness, and by how seriously they were taking their responsibilities, and by how seriously they were thinking about their roles in their babies lives, and what they wanted for their babies, and of course by how very young they were. They were just kids. Also by their humor; it was a really fun day. I went home and that night I started writing the story and thinking about Angel.

What were your biggest challenges with writing this book?

Probably the biggest challenge for me was extending the story. It was published, it was included in my collection, it was available online, and I really had no plans to revisit this family until 2 years later. I was working on some other stories about very similar family dynamics and they weren’t getting off the ground, and I realized, oh my god, these are the Padillas. How had I not recognized that? So I thought, huh, I’m actually still really interested in this family and maybe I’ll try to extend that first. But for a long time I thought that maybe it was cheating to extend the story, and I wasn’t quite sure if I was allowed to make changes since it was already published. It took me a long time to realize that actually there were no rules, I could do whatever I want. Once I was able to allow myself to do that, everything became easier. Even though it’s the same cast of characters and even though some of the writing is the same, somehow they exist in two parallel planes. Even the characters feel somewhat different to me.

This story is told from multiple points of view. As you were extending that first short story, how did you make decisions about what points of view to include? Were there any perspectives that were easier or harder to write from?

That was the really fun part, because the original short story was just in Amadeo’s point of view and Amadeo, he’s a pill, he’s an incredibly flawed character. He’s unemployed, he’s an alcoholic, he’s not at all present in his daughter Angel’s life. His point of view was sometimes tricky to be in, personally, because I would get frustrated with him, and I’d want him to do better. I would not have been able to write an entire novel just in his point of view, I wouldn’t have had much fun with it. So one of the pleasures was trying out Angel’s point of view and seeing what this experience was like for her. What is it like for her to have to move in with her father and her grandmother, when she doesn’t know her dad well and she’s never been given any reason to trust him? I really liked being in her point of view. She’s a lot of fun, and I like the way she sees the world. I like her wry observations and the ways she pokes fun at the adults around her.

I also enjoyed finding out what Yolanda’s experience is like, this mother who feels so responsible towards her family members and in fact has really privileged their needs over her own. So I knew that I would write about the core family. I also decided fairly early on that I would write from Brianna’s point of view, who is the teacher at Angel’s teen pregnancy program. I thought that Brianna’s point of view was important to explore because she’s an outsider, obviously to the family but also to the community. I had some concerns that if the novel only took place in this tight circle of the Padilla family that it might become claustrophobic, so I wanted to have another window on this family.

What was your writing practice like?

It took me a long time. It took years and years for me to write this, and part of it is that I was approaching the writing of this novel in the same way that I approach writing a story. When I write a story, I never have any idea where it’s going. I maybe start with a character or I start with a situation and then I’m just exploring and wandering around in the world of the story, having the character have interactions and hoping that things will happen and eventually they do. But it’s one thing to take that approach with a 25 page short story and it’s another thing to take that approach with a novel that’s over 400 pages long. I made a lot of false starts. I had whole storylines that didn’t pan out or I’d realize after 50 pages that actually I wasn’t interested in that, or that it wasn’t working, and I’d have to pull that out. I’m always envious of writers who start with an outline and just work their way through the outline. I’m not that kind of writer, and I wish I were because it would be much more efficient. On the upside, by the time I figure out what the story is I know my characters really well. I hope for the next novel that I find my way there a little more efficiently.

One aspect of the novel that I loved was the pacing of information sharing. This is a novel where everyone has secrets. As we jump from different points of view, we have this really effectively used character irony, and you also take your time sharing the secrets of the characters’ pasts with the reader. I imagine that was especially challenging when crafting such a long novel and especially without working from an outline. Can you tell me about how you found that pacing and how you decided what information to share when?

Thank you, I’m glad that the pacing works. I think a lot of that really came through trial and error. I really love backtory because when I’m writing backstory it’s the way I really get to know who the characters are, but I always end up writing much much more than I need and I end up cutting a lot. A big part of my revision process was just cutting away what I didn’t need so that the story actually could move because for a long time it didn’t; it was weighed down by the characters’ past. That took place over many, many revisions. Something that I thought was essential in 1, 2, 3 revisions ended up not being essential.

What are some larger conversations or topics that your book speaks to or engages with?

It’s funny talking about my own themes because my thinking about that always comes very late in the game; the story always comes first. But I think the main question that the novel deals with is how do we heal from these very old injuries, often generations of injury? How do we forgive, and how do we make amends for the injuries that we cause for the people around us? So I think that’s the biggest theme, but of course class is an issue, and race, and one of Angel’s main challenges in the novel is recognizing her own desire and actually pursuing desire. She starts off the novel pregnant so we know she’s sexually active, but she doens’t actually think about her own desire until a ways into the novel. So, her growing awareness of her queerness is also a theme.

Related to that, I was interested in the role of gendered spaces and communities in the book: we have the hermandad religious brotherhood, and the space of the morada, and then we have the Smart Starts! Group for teen mothers. I was wondering if you could talk about the role of gendered spaces and of gender more broadly in the novel?

Yeah, it’s true there really are. Amadeo seeks salvation in this brotherhood and feels pretty oppressed by all the women in his family— oppressed by them and also totally dependent on them. There are very clear gendered expectations in their community and in their family. Angel is following right in line with her grandmother, who’s a caretaker to everybody and still supporting her 33 year old son, without really questioning it until the end and then she starts being a little more outraged by it and angry at her father for not stepping up.

One of the first and most memorable images in the novel is the scene of Amadeo’s crucifixion as Jesus in the Good Friday procession. Can you tell me a little bit about that image—where it came from, how it developed as you wrote, and how it figures into the story as a whole?

I grew up Catholic. My family is from Northern New Mexico and we certainly share some characteristics with the Padillas. Catholicism has played a major role historically in that area. It was the reason and excuse for the Spanish conquest of the area and for really brutal treatment of the native peoples who lived there and still live there, and the establishment of missions was really important in the area. This practice of these penitences, these lay communities of men whose worship includes physical penance— self-flagellation and the like— that’s a really old tradition that has its roots in the earliest Spanish settlers in the area, and it persists today in these brotherhoods, which are incredibly important to the communities of these really isolated villages. Often there would be one priest for a whole bunch of villages, and these brotherhoods filled the roles that the church otherwise might have. They were responsible for burying the dead, they functioned as mutual aid societies, they became really politically essential during the 18th and 19th centuries. Then when writers and artists and journalists from the east coast, Anglo journalists, came in the early 20th centuries, they wrote these really salacious accounts of these religious rites and talked about the zealots and the blood and the gore. At that point the Church disavowed the practice and it went underground, but it still persists. I’ve always been interested in this practice that has such deep roots in the area, and I’m very moved by it. It’s not something I fully understand myself, but I want to understand it. It’s a really empathetic worship— it’s trying to worship Jesus by feeling what he would have felt, and there’s something about that, maybe because I’m a fiction writer, that I just find so incredibly moving.

Also, Amadeo is the least qualified guy to play Jesus. He’s the least Jesus-like guy in the whole community and yet he’s doing it. That situation made me laugh, and it made me think, well, what does someone in that situation do who is given a pass to play a role that he is so ill-equipped for? I’m interested also in where the line is between performance and true expressions of faith, and also the importance of community rituals, and I’m interested in how all of that can be mixed up and tangled.

Since this is your debut as a novelist, what do you hope this book says about you as a writer? What can we expect more of from you in the future?

Right now I’m working on a couple things. I like having a couple projects going on at a given point. I’ve been circling around and working on a new novel that still feels so new, I don’t quite know what it is yet. I’m also working on more short stories, as always. I never stopped writing short stories, and I will continue to write both novels and stories and read them both too.

What are you reading now?

I just read Patricia Lockwood’s No One Is Talking About This, which is another finalist, and what a gorgeous book. I also just finished Peter Ho Davies’ gorgeous incredible autofictional novel, A Lie Someone Told You About Yourself, and that book just blew me away. It’s been an incredible year for fiction!

Featured Book

-

.

The Five Wounds

By Kirstin Valdez Quade

Published by W. W. Norton & Company

Amadeo Padilla was hoping for redemption through his portrayal of Jesus in the Good Friday procession of his small town in New Mexico when his fifteen-year-old daughter, Angel, shows up pregnant after fleeing her mother’s house. Five generations of the Padilla family converge during the baby’s first year, bringing to life their struggles to parent children they may not be equipped to save.

About Kirstin Valdez Quade

-

Kirstin Valdez Quade

Kirstin Valdez Quade

Kirstin Valdez Quade is the author of Night at the Fiestas, winner of the National Book Critics Circle’s John Leonard Prize. She is the recipient of a “5 Under 35” award from the National Book Foundation, the Rome Prize, and the Rona Jaffe Foundation Writer’s Award. Her latest book is The Five Wounds. Originally from New Mexico, she now lives in New Jersey and teaches at Princeton University.

Photo Credit: Holly Andres