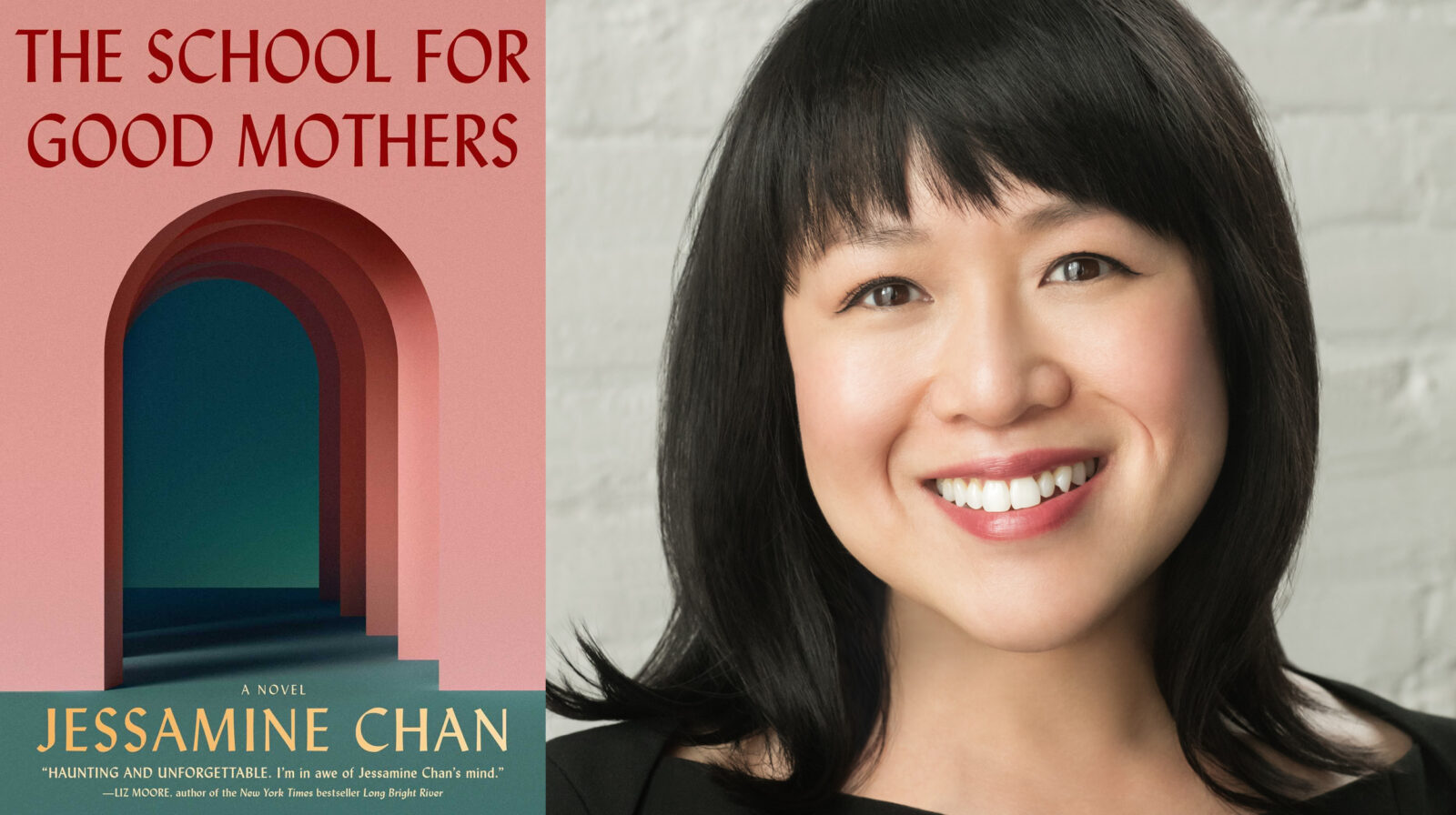

Jessamine Chan, author of The School for Good Mothers, spoke with Eliana Cohen-Orth, The Center’s Event Production Coordinator, in celebration of being shortlisted for the 2022 First Novel Prize. One lapse in judgment lands a young mother in a government reform program where custody of her child hangs in the balance, in this harrowing yet darkly witty story about the expectations of perfection in motherhood. The mother’s quest to prove her devotion to her daughter exemplifies the violence enacted upon women by both the state and, at times, one another.

I really loved this book! What was the first seed of this story?

The seeds came from two threads. I started the book in 2014 when I was trying very hard to get a short story collection off the ground and I was coming up with one terrible short story idea after another, as one tends to do. I was rejected from Yaddo and MacDowell for like the tenth time each, and I was working at Publisher’s Weekly at the time and I took all of my two weeks’ vacation to go get snowed in at a friend’s house in upstate New York for this self-created writer’s retreat. While I was there I had one really good writing day where this burst of inspiration hit me from these two things I’d been thinking about. I was in my mid-thirties and it was time to make a decision regarding whether or not my partner and I were going to have a child, so I was thinking a lot about motherhood already when I happened to read a New Yorker article by the journalist Rachel Aviv, whose work I admire so much, called “Where is Your Mother?” That story was about a single mother who left her child at home for a short time, the neighbors called the police, and after that, she never got her son back. I think beyond inspiration, that story planted a kernel of rage in my mind because I felt what happened to that mother was so unjust and it felt like the odds were stacked against her in a completely impossible situation. I really wished more than anything for her to have a second chance. It wasn’t exactly a conscious decision to write something in response to that article, but it had really lodged in my brain.

In that day’s writing— and this is the only time that this has ever happened to me in my writing life— an idea came to me fully formed. In six hours of writing, I had Frida and Harriet’s whole story, the women in pink lab coats, the mothers in uniforms, the secret tech stuff that I probably shouldn’t talk about because it’s a bit of a spoiler. I had Gust, I had Susanna, I had Tucker. I had the whole blueprint for the book from that day’s drafting, but it took me a really long time to realize that what I was working towards was a novel because, coming at it as a short story writer, it feels so daunting to say, “and now my new project is a novel.” It took about a year and a half to develop the first draft. The burst of ideas happened quickly, but the actual development was slow.

Can you talk a little bit about that development? What did your writing practice look like after that big burst?

I tend to elicit gasps when I describe my writing process because it’s so snail-like. I write longhand, exclusively, which really makes everything three times slower. I would type up the pages every so often and I didn’t start cutting until I got to the last scene, which I think is pretty unusual and also totally inefficient. By the end of the first draft, I had this completely unmanageable number of pages. The cutting was fast once I got to it, but I’d spent my whole professional life as an editor and I knew that if I started cutting and tinkering I would never get to the last scene. I would spend like eight years on the first chapter. So, I forced myself to write until the very end and then see what I had made. I will say that writing longhand allows me to feel a lot more free, I can just focus on the ideas rather than making them perfect. I think that helps me deal with some of my perfectionist tendencies.

When you were writing it, what were the challenges that came up throughout this process?

Um, how much time do we have? So many things! I think for me one of the challenges of writing a novel as opposed to writing a story is that writing a story feels possible in terms of the finishing of it, the end doesn’t feel that far away. Certainly, some short stories take years and years, but I wrote this book from 2014 to 2019, a lot of which was spent working on it alone. So, I think one of the hardest things is to just keep up the faith and to believe that the project is going to get done and that what you’re doing matters, and this thing that matters so much to you will matter to other people. It’s so subjective, what someone wants out of their books, so you just have to keep at it with this blind faith and that’s hard to drum up on the day-to-day. It’s hard when the end is years away rather than months.

One of the remarkable things about the book is how you expertly craft this near-future dystopia where things are very recognizable and in a lot of ways feels very present, but there are still definitely elements that feel more sci-fi and are developed past where we are in some very eerie ways. I’m curious about how you developed those more speculative elements while grounding it in such a present feeling?

Thank you for seeing the book that way. I wanted the book to begin in the real world as we know it because I knew I was asking readers to jump into this slightly different world with me, and I wanted them to be really rooted in Frida’s perspective first. If they see the world through her eyes, they’ll be more invested in her emotional journey before we start adding the more fun, sci-fi, speculative elements.

I will say that my interest in my sci-fi and speculative stuff comes from a very pure and playful place because I’m a total Luddite. I had to record an interview on Twitter Spaces a couple of months ago and that was a total heart attack like, oh my god, am I going to hit the right buttons at the right times, how do I connect, where is the link? Stuff like Instagram Live also gives me a heart attack. So I’m not exactly conversant with machines, it’s more like I’m interested in the idea of technology more than the machinery.

One of the key stages of developing these ideas was talking through them with my friend, the poet Keith S. Wilson, who in addition to being an award-winning poet is also really versed in the latest technology. We did a lot of brainstorming over email about how the tech might work, this is what it might be in the future. He gave me the very eerie and troubling suggestion that you could have the machines do what our phones do, so some of the slightly more advanced technology is based on what our smartphones already do and how we’re monitored by our smartphones, but just pushed a little further on. The hard thing about writing any speculative stuff that takes years and years to finish and then another two years to get published is that you have to hope that it’s far enough along that it’s not going to be real by the time the book comes out.

As you were working, was there anything that caught up to what you were writing in that way?

I think in the real world if there were advances like this they would probably be used by the military and not child protective services, and they would probably be used for capitalism more than trying to reshape the family, but I was trying to think if you had these advances and if you had a whole bunch of money, what are some more nefarious purposes you’d use them for. One thing that’s probably a little bit strange about my family is that we talk about surveillance and end times and climate change and dark topics more than the average family. My husband is very anti-social media and big tech and we talk about that a lot in terms of all the data that I’m giving to social media by having my author account, and things like that.

The ways in which the world has changed since I started writing have been more political than technological. To lead us on a totally different tangent, I was not expecting the world to be quite so grim for women in 2022. It’s made me reflect on how you can’t exactly imagine the world your book is born into. While I feel so grateful to be part of a larger conversation about women’s rights, the fact that this conversation is so urgent is also tragic because right now it feels like women’s rights are under attack in every way. The fact that it ended up being so well-timed in that way fills me a bit with despair.

Yeah, the timing was really chilling. What were the larger conversations you had been intending to engage with when writing the book?

I think the topic that I was intending to engage with is the question of whether or not there can be one set of universal standards for parenting, and who is making that judgment and by what authority, and whether or not those judgments can be free of bias, whether that bias be about race or class or culture. So, that was the conversation that I expected to be entering. I was not expecting, and again this is because of everything that has changed politically, I was not quite expecting to be part of the conversation about female bodily autonomy and women’s choices. It’s hard now to develop new story ideas or new projects that aren’t about that because it’s on my mind so much.

What’s been amazing is to be part of this conversation about writing about motherhood too, because it feels like there’s this whole new wave of motherhood novels that really dismantle the fantasy of motherhood and talk about what is psychologically or economically difficult about being a parent in America. It’s really exciting that there is a conversation about that now, but of course, the fantasy would be that all these books about motherhood and about women’s rights were read by the people in charge who are the very tiny number of people who actually decide this for the rest of us.

One thing that I was thinking about as you were talking about these impossible standards of parenthood and who gets to make these decisions is that it was really interesting how big a range of transgressions there were for parents that were at the school for good mothers. You don’t shy away from some quite disturbing acts, while there are others that feel so completely unfair that they’re in there, but there’s empathy for all of them. You have these characters grappling with the questions of if anyone deserves to have their child taken away, and comparing themselves to each other, but also a deep suspicion of this system being helpful for anyone. How did you go about developing this moral complexity? Were there challenges of finding this balance as you wrote?

I thought of the world of the school as a social satire in a way where it’s taking some elements of reality but really pushing them in outlandish directions. In terms of the range of transgressions, I wanted to gesture towards the tragedy of how having your child taken away disproportionally happens to black and brown women who are poor. I wanted the book to reflect that reality while also expanding upon that issue to ask who does the system serve and who does it punish. One of the things that came up in my reading is how in some cases the judgment is not about unfit parenting but about poverty. I wanted to build some of that into the book while also wondering if we’re talking about not just the child protection services system, but our larger culture and how it views mothers. What would it mean for a mom to be out of line, and what would happen if people were policed for complaining about their kids on social media?

When my copy editor read the book one of her notes was her heart was beating really fast at the section where they were punished for complaining about their kids on Twitter, as that’s the new vanguard, that you’re actually being watched all the time, not just for what you’re doing but what you’re saying about your children. It was taking this kernel of reality and also critiquing mothering culture where the dominant narrative is about upper middle class white women. I think that the main narrative we’re fed about what a good mother is very specific about race and class, but it’s supposed to apply to everyone.

This is a bit of a spoiler, but I wanted to talk about the robotic dolls that are stand-ins for their daughters in the school of good mothers, which were such an eerie and an increasingly complicated element as you see Frida develop her relationship with Emmanuelle, her doll, while also figuring out what her relationship with her daughter, Harriet, looks like over the phone. What was the development of the dolls like both as a scifi aspect and as such an emotional crux of the novel?

I think the emotional crux part, which is music to my ears, was kind of a surprise to me because that was something that had to be developed in draft after draft. I will say there was probably a little less humanity to the dolls in the earlier drafts, but that’s something that changed as I became a mother myself. I think there was a lot more tenderness and love woven into the book once I was experiencing this thing that I had only been able to access in my imagination.

I think one of the seeds for the dolls came from that New Yorker piece I referenced at the beginning of our conversation. When I read about the way that all the representatives of the government talked to the mom who was the focus of the story, it felt so clinical that it almost reminded me of science fiction. They talked about maternal instinct and the tone with which she spoke to her child, whether or not she was being too affectionate or not affectionate enough, and it felt like they were trying to ask about all these intangible things and whether or not they could be measured. The decision was, yes, they could be measured, and you could decide whether it was right or wrong. That idea was really fueling some of the development of the dolls.

But I will say that besides the intellectual underpinning, the dolls were also just a way to have fun and entertain myself because I could have them do things that real children don’t do. As I worked on the project more and more, I came to realize that creepy realistic life-sized baby dolls are all around us. You’re working with one if you’re in a hospital childbirth class. If you look through any parenting magazine there will be these ads for these incredibly lifelike real-sized baby dolls that cost $200 or something. So, I was also subconsciously responding to something in our culture where the idea of owning and manipulating a baby figure is already all around us.

Issues relating to mental health are woven through this story in a central way. Could you talk about how that figured in?

You know, that also wasn’t as present in the early drafts. I think what happened is I wrote the whole first draft before becoming pregnant, and in order to get pregnant my internist made the decision, which I question now in hindsight, to have me go completely off my antidepressants. I was on a particular antidepressant that pregnant women are not allowed to take, and after being on them for ten years I went off them very quickly. I had a major mental health crash. I was put back on medicine where I was functional, but I was not myself throughout my pregnancy and for the first ten months of motherhood.

The reason why I’ve been trying to talk about it a lot in interviews is this is not an uncommon experience—whenever I mention to people about the mental health struggles I had in order to have a baby, someone will say that happened to their sister or their coworker or themselves—, but no one ever talks about it. There’s a lot of stigma around having any depression or anxiety issues as a woman trying to get pregnant, as a woman who’s nursing, as a new mother, and you’re supposed to just take it. You’re supposed to just suffer in silence and be grateful for what you have. I wanted the book to challenge that notion. I decided to weave that into Frida’s story partly as a way of dealing with it and also as a way to try and counteract the stigma around issues of maternal mental health.

I think what’s been one positive about the pandemic is that we are looking at maternal mental health and all the psychological burdens of motherhood and how much pressure women are under all the time now. The pandemic has brought all those things to light.

That was such a disturbing part of the book, this emphasis on the impossible level of selflessness and emotional shut-down that these mothers are supposed to have while they’re all dealing with so much.

One thing that I thought would be one of the hardest standards to meet in the book was for the mothers to be happy all the time, completely focused on their child, and completely selfless, all while being cheerful. I can think of few things that would be quite as impossible for me. I also wanted them to get punished if they get bored or distracted, things that as a parent you’re just dealing with all the time. You can cycle through all those emotions in the twenty minutes it takes to get your child out the door—or the forty-five minutes it takes to get your child out the door is more like it sometimes. That mind control aspect is something that I wanted to play with. The elevator pitch that I gave for the book for many years is that it’s like 1984 but for moms.

Since this is your debut as a novelist, what do you think this book says about you as a writer? What’s next for you in the future?

This year has been incredible in so many ways. I think one of the strangest things about publishing a book is you go from being a completely anonymous person to speaking to the press or to readers at events. My writing life is very charmed, but my home life is still very quiet and mundane. It still feels completely surreal. It was only this September that I finally moved all the draft files off my desktop and put them in other folders to accept that the book is done now and that I’m not still tinkering. In terms of what’s next, I think I’m just learning how to write again. I thought that sitting down to work again would be so much easier the second time around.

I tend not to think about the reader when I work. In order to get crazy ideas down on the page I have to pretend like nobody’s ever going to see it. It doesn’t matter what I say, I don’t need to worry about anybody being mad at me, I don’t need to worry about my parents seeing it and being upset, that kind of thing. That pretending is a little more challenging now, but I’m trying to get back to that more pure and innocent place. I also have realized that I’m probably the kind of writer that’s a little more on the secretive and superstitious side, so I’ll hopefully pop back up after a number of years to be like, “Here, I worked on something, and now it’s done!”

Featured Book

-

.

The School for Good Mothers

By Jessamine Chan

Published by Simon & Schuster

One lapse in judgment lands a young mother in a government reform program where custody of her child hangs in the balance, in this harrowing yet darkly witty story about the expectations of perfection in motherhood. The mother’s quest to prove her devotion to her daughter exemplifies the violence enacted upon women by both the state and, at times, one another.

About Jessamine Chan

-

Jessamine Chan

Jessamine Chan

Jessamine Chan’s short stories have appeared in Tin House and Epoch. A former reviews editor at Publishers Weekly, she holds an MFA from Columbia University. Her first novel, The School for Good Mothers, is a New York Times bestseller and a Read with Jenna Today Show Book Club pick. She lives in Chicago with her husband and daughter.

Photo Credit: Beowulf Sheehan