December 2, 2023

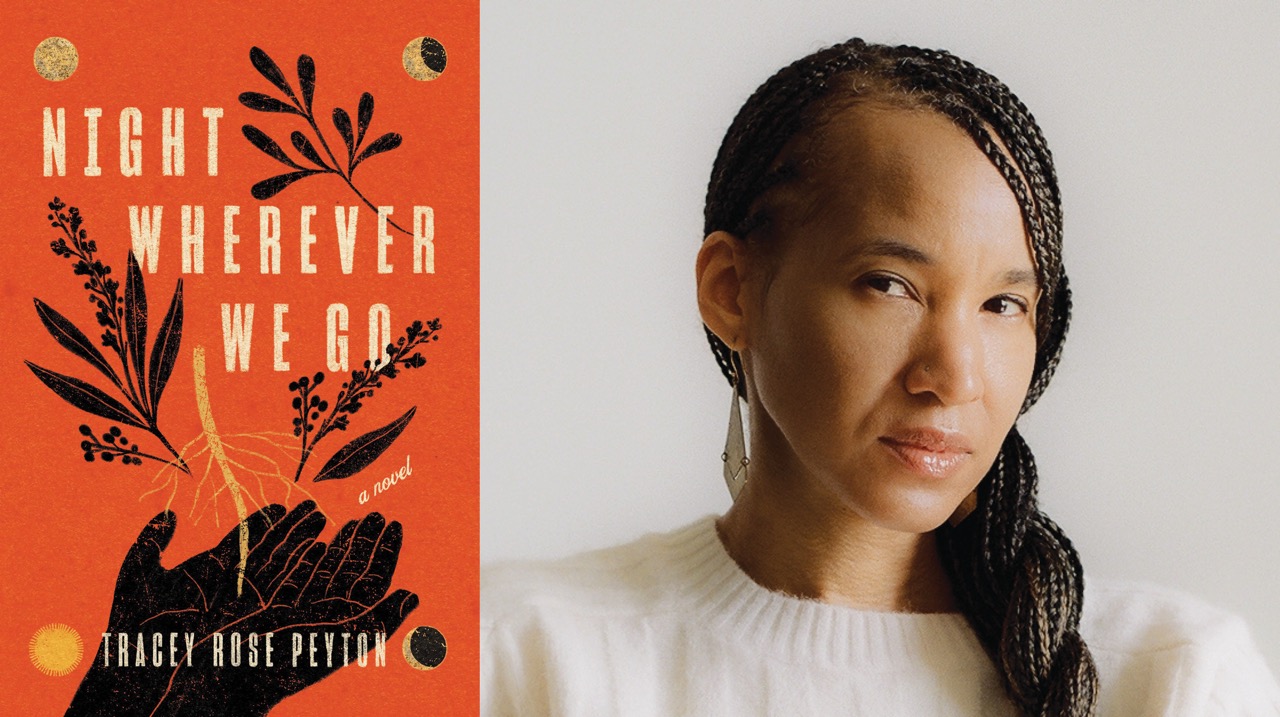

Tracey Rose Peyton, author of Night Wherever We Go, spoke with Majo Restrepo in celebration of being shortlisted for the 2023 First Novel Prize! The novel follows six enslaved women who come together to fight back against a plan to turn around a struggling Texas plantation’s financial prospects by hiring a “stockman” to impregnate them. Nan, the doctoring woman, has brought a sack of cotton root clippings that can stave off children when chewed daily, but the consequences of a pregnancy or being discovered would be severe.

I want to start with saying thank you for taking the time to write such an extremely tender, complicated, interesting novel. I’m wondering what the first seed for this book was. What couldn’t you stop thinking about that led to this story?

Thank you for that. The first seed of the novel is a book by Paula Giddings, she’s a social historian, and she wrote this amazing history of Black women in America. The book is called Where and When I Enter , and it’s this political history of Black women in America from emancipation all the way through to the civil rights movement. She has has chapters on slavery where she focuses on different forms of resistance, like work sabotage or slow downs, but gynecological resistance. She tells the story of 4-6 women on a plantation in Tennessee who, for 20 years, controlled the birth rate on their farm. Over that period, whenever their master tried to swap out the women or purchased a new woman, they typically miscarried by the sixth month and only 2 children were born in that period. He found out later that there was an old woman who was giving them an herbal remedy. The story comes out because it was in a medical journal. This was the 1850s, when doctors would have these conferences to talk about the “problem of fertility” and how enslaved women were wiley and these were the things you needed to watch out for, so it was told as part of that conversation by the doctors who were employed to try and prevent it.

I’m wondering, given that sort of seedling of an idea, why did you choose to write a novel? Why did you choose fiction, and not a researched nonfiction account?

I went to grad school at the University of Texas Austin, where they also have the Dolph Brisco Center for American History. When I first started to work on this, I pulled some primary sources out of the archives, and I started looking through this lady’s letters and they were all written in this beautiful handwriting, very ornate penmanship in script, and I could not read her handwriting for anything. So I thought, okay, this is why historians are important. Let me just go back and read this published scholarship and work on my novel.

In this novel, I really felt, even in the extremely painful moments, your care with embedding the lyricism of your craft. I’m wondering how you balance the poetics with the history— not shying away from revealing what happened, while at the same time creating what is an extremely beautiful text?

Thank you. Language is very important for me and is not something I take lightly. That could just be the tradition of writers that I hope to be writing in— your Toni Morrisons and Alice Walkers. I feel like they were very powerful in the way they used language,and I want to honor that. Sometimes it’s hard for me when I’m reading, and the story could be amazing and they have the beats and it’s propulsive, but if they’re not doing something on the line level they’re missing an opportunity. What I love about fiction is how all those pieces work together.

With a book like this I was really interested in the interiority of the women, and I wanted to create space for the complexity of their thought, and the complexity of their feeling, even if that’s not necessarily articulated in a way that we would expect or consider complex currently. I think sometimes when people are considered illiterate, people often think they’re not complex people or their thoughts aren’t complex or that they’re capable of a certain type of intellectual rigor, and I wanted to be sure to portray that in these women.

I was taken by that too because I found that there were moments where the “we” really moves the sentence forward, but the text is very partial to each of the women’s own personhood. It seesaws in a very graceful way between what’s happening to them collectively and how each of them are individually acting in their own way at all times. How did that work out for you? How did you choose when to use “we” and when to add that extra detail for each character?

I’m really interested in this tension between the group and the individual. Especially in Western society, and America specifically, there’s such a focus on the individual—what you individually care about, what you individually think about—that it’s somehow more important than the whole. I think that has done real damage to us as a society. So I was interested in this idea that it’s the collective that’s complicated—they didn’t necessarily choose to be together, they love each other but don’t want to be forced to operate as this unit—and the tension between being a group of women and being very clear that they all have their individual desires.

Earlier drafts of the book were written primarily in third person, and then I read Julie Otsuka’s The Buddha in the Attic, which is one of my favorite novels, and I love that she was playing with this idea, also with a group of women. She plays with the chorus, which sometimes becomes this kind of incantation. The brilliance of the novel is that the “they” is always changing. The “we” remains the same, but the “they” is sometimes the white people, the husbands, the children. I was struck by that and thought, does that offer you anything in terms of where the novel’s going? At that point I was really trying to break the novel in my mind.

There’s so much resistance to novels about enslaved people, there’s so much resistance to talking about that history, all for different reasons—some valid some not—and I think for that reason the novel includes so many intersections, because I really felt I had to earn the space. I had to tell people stories that were lesser known or underexplored, so focusing on a smaller plantation, Texas, people running further south versus running north, women…I felt like I had to do numerous things that ensured people that they didn’t already know this story, this is not a story they’ve heard before.

How would you say that history and our present times influenced the choices made while writing the book?

I think part of my interest in the subject matter itself was what was happening with reproductive rights, period. Being a 20-something walking into Planned Parenthood and it’s like walking into Fort Knox. Then reading Dorothy E. Roberts’s Killing the Black Body, where she’s drawing this throughline between what’s happening with birth control now and coercive birth control that was being enforced on women on welfare or lower income women of color. She was writing about people who were incarcerated and were giving birth handcuffed. It was all these things in the present that looked very much like the past. That throughline has always been interesting to me and present to me. You could always see the ways these particular tensions around who mothers and how and why and who we should encourage to mother and who we shouldn’t, are these continued battles in American consciousness for different reasons. So for me, that’s always been in the background, but I didn’t expect to write about it. Then Roe happened, and suddenly it was more relevant than I expected it to be, and maybe more relevant than I wanted it to be.

The other thing that comes up is when I was doing research around Black midwives under enslavement. I knew some friends who were doulas, and I remember when they first started doing it it was very crunchy, it was very strange. Right now I feel like it’s very mainstream but back then we were like, “Oh really? You’re going to go to a birthing center?” In researching Black midwives in the South and even talking to my own family—my mom is from Georgia, where I originally set the novel, and she’s one of seven and all of her siblings other than her baby brother were all delivered by midwives—you realize, oh, you’re wondering why is the Black maternal mortality rate as high as it is? Maybe because Black midwives were forced out of the business in the seventies. Everything has a throughline and research allows you to see it more clearly.

Going off what you said about how it was originally set in Georgia, I’m curious about what it was about Texas that you knew was the right fit for the setting of the novel? Texas at that time was so interesting—the Louisiana Purchase has gone through and people are moving over there, and the Haitian Revolution is happening which is why France had to sell everything, and there are all of these different groups of people who speak different languages, practice different religions, coming into this space, so I can imagine that all being very rich to draw inspiration from.

Part of it was, as you said, being inspired by all the different people who were there and all the different shifts that were happening, especially with all of these people moving to Texas to make their fortune and to expand the American empire as far as possible. I didn’t know a lot about Texas and more than that I didn’t really know about the role of Texas in slavery. I feel like the stories Texas often tells about itself are about the cattle runs and the long goodbye trail and these particular stories about outlaws and Jesse James and all that, and we don’t even tell that story as being connected to the Confederacy, right? That story’s often like,”Look at these rebels,” but not mentioning that they’re Civil War rebels.

So, I got really interested in the role of Texas and how much Texas was shaped by slavery, and how Texas being farther away from the markets affected their practices in slavery. Because of its location outside of the quote-unquote U.S, almost anything is possible, people do anything.

Different freedoms are available the same way that different freedoms of barbarity are available, this is a space in which people also found their way toward freedom given all of the nuance in that space. I’m fascinated by the nuance in your book, too.

I’ll say some of that too was inspired by reading the stories of farmers who moved to the West. There was one farmer in particular, I remember reading his letters, and the letters were over a ten year period, and you could see how the beginning of the letters are very much about Texas being Eden—everything is growing off the vine and you don’t even need to do anything—and then a drought happens, and then a freeze happens, and then his first born dies. It was this arc about people moving into rural places and having to contend with the land there.

And learning the language of the land. It’s interesting how each character brings their own knowledge from where they’re from, and use that knowledge as a form of manipulation. I think also the proximity to Mexico is really interesting, and further diversifying and creating nuance.

I was interested in the frictions between Black enslaved folks who were brought there and the relationships they would’ve had with the Americans, the Mexicans, the Tejanos. I was interested in both the collective struggle, but also the tensions that would come about from everyone having different objectives, everyone having different loyalties. I was really interested, and surprised by, enslaved folks who ran to Mexico and the Mexican colonies that they created there. There are a couple people who are doing a lot of research about the colonies that did exist and those Afro-Mexicans who are descended from enslaved folks, so that was inspiring to me.

Going back to letters, in Chapter 22, when Noah leaves and he’s writing to Sarah, the story takes on an epistolary format. How did you want that to serve the narrative?

One of my favorite sources are letters between enslaved husband and wives; they’re some of the most beautiful, heartbreaking things you’ll ever read. One of the things I was really taken with when I read those stories is the deep love people had for one another, how they would walk 5 miles or 10 miles every week to see their loved one and couples that would only get to see each other two or three times a year because the people who’d enslaved them had moved away. You read these stories of folks who, maybe after emancipation were able to be back in communication, but maybe one of them had remarried, and the letters are just heartbreaking. That always stayed with me and I wanted to incorporate that into the story.

Something that I found to be so pure and so heartbreaking was the way the narration shifts into a simple future tense at the very end. It delivers this impossible hope.

I will say that came late. I knew the book was going to end where it ended, and I knew there was going to be a pretty dark ending, but I was very cognizant of the conversation about “trauma porn,” and what audiences have the stomach to deal with. Not that I’m particularly interested in gratuitous violence, but if I take you through some form of darkness I’m going to hold your hand through it and make sure that it’s not a spectacle for the sake of spectacle. It’s there for a reason. It has value. And I’m not just leaving you there to wrestle with the trauma of that particular moment.

What does your writing process look like?

I drink a lot of tea. My schedule has changed a lot over the years. The first draft of the book, I was still working in advertising full-time, so I was writing in the evenings. I had the gift of time to write the next draft because I was in grad school. Now it’s a little bit weird because I’m in between projects and I’m researching for the next project, but just having blocks where I write during the day and give myself some time, and not being so much about work, is great. I need that level of boring routine where you get up in the same place and you exercise and you’re at the desk by a certain hour. Even if you’re not doing well, you still touch it and be with it consistently.

If I’m correct here, you’re currently in Los Angeles, you’ve lived in New York for a while, you lived in Texas, and you’re from Chicago. Have all of these spaces contributed to your writing style, technique, essence?

I think in certain ways. I also lived in DC when I was in undergrad, and I was studying film so I was really thinking about how to communicate in images. I was learning how to be a director of photography, so I was very serious lighting and things, and I do still think in some ways I’m really grateful for that training, learning how to see in a particular kind of way. I feel like it helps me think about how to enter a scene, or how to visualize a scene. Sometimes if I’m stuck in a short story I’ll think about how, okay, if this were a first scene in a movie what could that be?

And New York, I still miss New York. When you’re thinking about New York and L.A and Texas, it’s just thinking about the relationship with space. People in space, community in space, and the different feeling they give you.

Is there anything you would say to the Tracey who started writing this book years ago?

It’s really hard to keep going. I think a first novel is a marathon and an act of faith. At any point you’re climbing uphill. I’ve been with this book for about a decade, and the only thing that kept me with it was the women at the heart of this story and what the story was about. I think if I was writing a contemporary novel that was somehow based on my life I probably would’ve found less conviction, but because of what the story was about it felt important to me. It felt like something that should be told. So I think it’s just, “Keep going.” I feel like that’s the answer to everything, to just keep going.

Featured Book

-

.

Night Wherever We Go

By Tracey Rose Peyton

Published by HarperCollins / Ecco

Six enslaved women come together to fight back against a plan to turn around a struggling Texas plantation’s financial prospects by hiring a “stockman” to impregnate them in this unflinching portrayal of America’s gravest injustices. Nan, the doctoring woman, has brought a sack of cotton root clippings that can stave off children when chewed daily, but the consequences of a pregnancy or being discovered would be severe.

About Tracey Rose Peyton

-

Tracey Rose Peyton

Tracey Rose Peyton

Tracey Rose Peyton received her MFA from the Michener Center for Writers at the University of Texas at Austin. Her short fiction has appeared in Guernica, American Short Fiction, Prairie Schooner, The Best American Short Stories 2021, and other outlets.

Photo Credit: David Katzinger