November 28, 2023

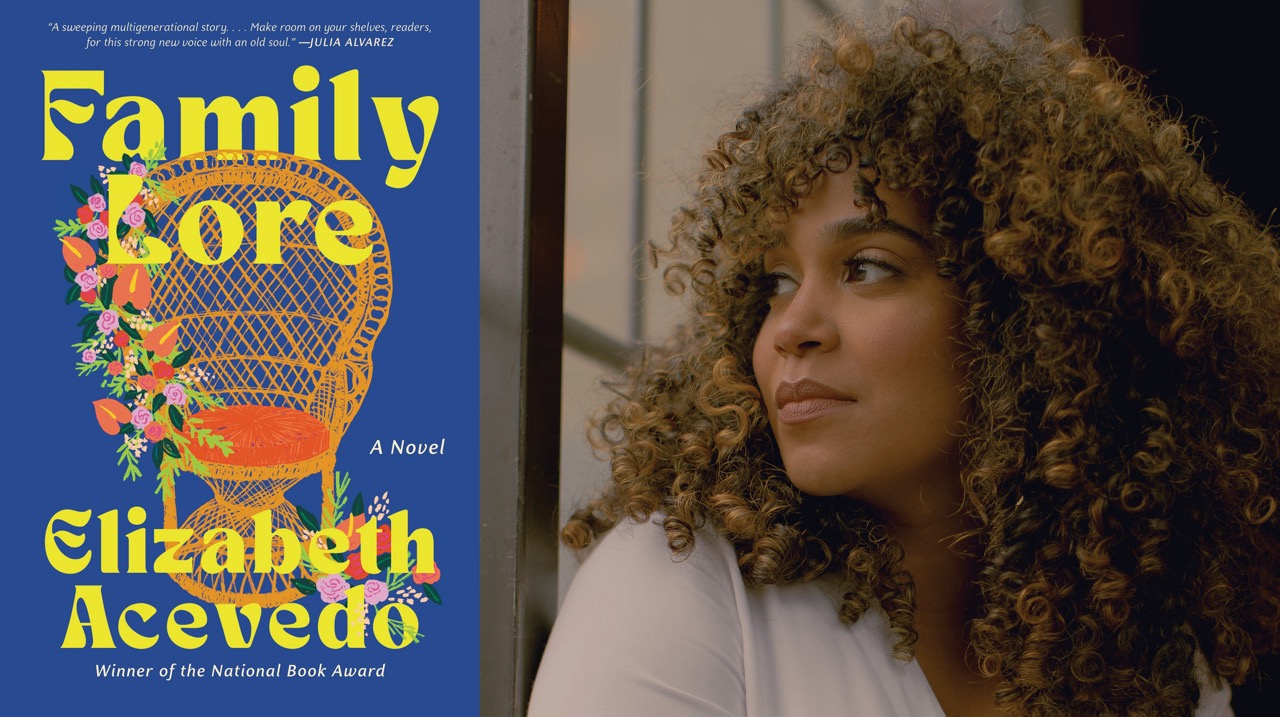

Elizabeth Acevedo, author of Family Lore, spoke with Denisse Reyes in celebration of being shortlisted for the 2023 First Novel Prize. The novel begins with Flora calling her family and community together for a living wake. Flora can predict, to the day, when people will die, and her sisters wonder if she has foreseen her own death or someone else’s. In the three days leading up to the wake, Family Lore traces the lives of the Marte women, weaving together past and present, Santo Domingo and New York City, in this indelible portrait of a family full of secrets.

Let’s start at the beginning. I’m curious what you couldn’t stop thinking about that led to the creation of the story. Was there something on your mind that you felt you needed to say?

I think the very first kernel would have been visiting one of my aunts, who had just relocated to New York from the Dominican Republic, and she’s such a gangsta, such a hustler, she was just thriving. She was a business person in DR and came here, like, aight I’m gonna figure out how to hustle, and had a whole daycare enterprise within a couple of years. My mom is one of 15, and I was looking at all the aunts and uncles as they were arriving and realizing what they brought with them, and how different they were from each other, and how they could be raised in the same place by the same parents but be so particular in how they moved through the world.

I think, if anything, the seed was just observing my mother and the nine sisters and thinking how I would love to write a short story collection, one story on each sister. But then, as I got older and kept watching and reading, it became about how we are different people to different people. Like, how is my relationship with my aunt one that’s so tender and loving, but her relationship to her own daughters is maybe more complicated? There’s a way she can be soft with me but has to be different with them. Or, my relationship with my mother is one way, but there’s a way she can mother her sister that feels different than how she mothers me. So then it became about how we know each other, and are known by each other. That became the central question: Who were these women, depending on who they’re with?

That relates to a question that I have about the structure. Each of the characters’ stories are told through first person narratives. Was that because you wanted to forefront how all of the characters thought of themselves?

Ona’s in first-person and she’s the interviewer, so you’re getting these stories that she’s kind of prompting from people. They’re having memories but they’re also in conversation with her throughout the book. I think the structure was one of storytelling; it’s this question of, once I have figured out how these women are known by each other, what are the stories they tell about themselves? And what are the stories where we see them more as cameos and we get new information? I think that feels true to how family stories work, that you learn about people based on what your relations say, and then you meet them and you’re like, oh, that sort of was colored by how my mother feels about you. And now I have my own relationship with you, and I have to think about what I know that you don’t know I know, because of what they know. So, yeah, the structure was intentionally non-linear, intentionally contradictory, intentionally piecemeal, because that feels like how family stories—if you’re from places where oral storytelling is the way that you chronicle a family’s movement—work. Even the writing of this story was a little bit of cobbling it together. I had, like, 200 Post-its on a wall, and I think the book reflects that energy.

Could you tell me more about that process of writing? Do you have any rituals?

This book had a lot more ritual. There was a lot more prayer. Naima Coster, who’s a friend and an author that I love, gave me this little candle that I would burn all the time, and I liked that this other writer, who was probably writing at the same time, gave me this thing that now is a part of my structure. I had a doll that my mother gave me, a muñecas sin rostro, which is a famous kind of Dominican blank-face doll, and I broke her twice and re-glued her. She would sit on the desk and there was something about that doll watching me work in her broken, put-togetherness that also felt like this little guardian.

This book was written unlike any other book. I don’t outline, and that was true for this book, but I did have my guides, because it was six characters and I had to really have some type of idea of what was going to happen to each one of them. So, I wrote it in the way that you read it. You get these events, and then it was like, okay, now I’m going to have to sew it together. They’re not separate narratives, they have to weave in and out. One thing you learn from this character is something that will actually echo in a different character’s perspective later. So, it was many layers of writing each individual character, and then rewriting the characters, and then seeing how they worked in the larger narrative.

Were there any challenges that you faced while you were working on the book?

I mean, you just heard my process, this whole thing was a challenge. Halfway through I was like, “What the fuck am I writing?” Because you start and it’s exciting and invigorating, and then you’re like, “Oh, I have to bring it together.” I don’t think I’m a conventional writer, and I don’t think I follow a lot of the narrative conventions necessarily, but I did want a sense of some closure, and of satisfaction. That is important to me. I think that is a fixture of fiction, that you arrive somewhere, even if it’s not super neat. So, it was a challenge to take all the moments that I love and make it a bigger thing than just the separate moments.

I also think it was a challenge to trust that this book wasn’t going to be for everybody. It is a book that requires work— work to keep track of the characters, work to keep track of timelines, work to buy into the structure, which is doing a lot of things at once. It’s kind of a book within a book. I kept thinking, do I want to strip this down and make it simpler? Or am I okay with the fact that this is a big, messy book,? And that’s the point, and I’m okay with the fact that some folks may not be able to get into it. As someone who wants to be liked, it’s something I’m constantly having to challenge in my work, but hopefully it does something more interesting than being liked.

Since you’ve written young adult novels before this one, did you feel like there was more pressure with this novel?

I don’t know if it felt like pressure. I think on one level it felt freeing because there was a different kind of flexing that I could do, in terms of vocabulary and sentence structure and weirdness. I could lean into some of those things without being worried about isolating a young person who picked up this book. I think with adults, I’m a little bit more like, you know, it’s on you.

I do think that there was a little bit of not wanting to be known as one thing. I don’t want to be known as just a verse novelist. I don’t want to be known as someone who only writes about poets. And I didn’t want to be known as someone who only writes for children. I’m looking at folks like Jacqueline Woodson and Julia Alvarez and Lucille Clifton, who wrote for young people and also wrote for wide general audiences. I don’t want to be boxed in as to the kinds of stories I can tell. A story arrives and I follow it.

The only pressure I might have felt was that I worried if it flopped, people would take that to mean that I should just go back to what I know. Which I don’t think I would do, I have too many ideas that won’t work for young people, but I still worried.

Did you choose New York City as the setting of the novel because it was somewhat related to your own family history?

I did a research trip to the Dominican Republic, to where my mother and her siblings were raised, and we went back so I could envision and imagine it. But, I’m writing about the 1940s, ‘50s, ‘60s, ‘70s, in the countryside of DR. I’m writing about women who are post-menopausal, menopausal, at different stages of their life. There were so many unknowns that I needed an anchor that I knew, and so for me growing up in New York––knowing Yadi and Ona’s environment and what raised them, and the kind of language they had access to––was that anchor.

I think there’s something also to be said about the way New York allows a certain proximity of families when they move. There’s a familiarity of Dominican culture that feels really welcoming but also can be jarring for folks. I think there was a lot to be said about what it means to be Dominican in that particular neighborhood by Columbia University, and the access you have and the access you don’t have, and the hopes and dreams you might have as you walk through that campus, and what is possible. There’s something really rich about that neighborhood; it’s not Washington Heights, it’s not the Bronx, but there is this enclave of Dominicans there that are surrounded by affluent academia but are outside of it, and I think that does something. I wanted to think about the mentality of looking out your window and only seeing brick walls, but having this desire for more.

What I really enjoyed about the book was that the ending felt like a beginning for a lot of characters. You’re left with a lot of hopes and dreams for everyone while also being happy that they find their voices in different ways. I’m curious to know if there was anything that you were hoping that the readers would get from reading the novel.

I think you really honed in on this question of what does it mean for something to be closed, or something to be done: a book, a life, or our relationship to people once they pass. I think there’s this urgency we have as humans to want to avoid closed things, wanting to avoid death, wanting to avoid losing, and I think near the end when Flor is continuously saying, “it’s about a good life, and a good death,” it’s about the fact that there is another life, that we came from a life and you turn to another life, and that it might not be so clean cut. Maybe it’s because I’m reading all these genetics reports, and they’re like, “We’re going to live forever! We can do this! We can do that! There’s stuff being tested on mice!” And I’m like, “I don’t want no mouse water!” Death is necessary. It’s important. We need transitions, we need to go, we need to know that this is finite.

I think that the book is offering this sense of goodbyes being hurtful but necessary, and if we create rituals around how we live and how we say goodbye, there might be more ease. If we can say things while people are here versus waiting until that communication is different, it might require a little bit more faith. I think for me it’s all about allowing wonder to exist, and making peace with the fact that there’s more than we know. What’s beyond might be easier to approach if we’re not so scared of the fact that we just don’t know.

I loved the concept of a living wake. Was thinking about all those things about death how you got to that idea?

I don’t write right away. I’ll have ideas for years and just keep filing stuff. So I had, “I want to write about my aunts,” and then I went to this conference that was very similar to a TED talk. People were presenting different research, and there was this person presenting on different rituals of death and dying. He talked about people who encapsulate themselves in a dirt pod and become a tree, and biodegradable caskets. There are so many choices that people make about dying and death while they’re living, and those choices have changed over time. For maybe two minutes, he talked about living wakes. He was looking at this Tejano man and his family, and he was chronically ill and just taking that moment to say goodbye. And I was like, Dominicans would never do that. We’re too Catholic, we’re way too afraid of talking about death.

So then I was thinking about, well, who would be the kind of person that would do this? Who would have such a relationship with death that they are not afraid to do this? Who would actually realize this is a gift they can give to their family, to give them this moment to model what a goodbye could look like? And Flor––and her gift and her relationship to death––began to make sense to me. But it was this little thing I saw that I didn’t think about ever using in a book. I just filed it away. Then things kept happening and I kept filing away and one day I realized, oh, these are all the same story. These are all the same morals, and I just have to figure out the pieces and how they’re going to work together.

What has been the most surprising to you about the public perception of the book?

I thought I would get a lot more questions about the pornography in the book, which is great because I don’t know if I wanted to answer too many questions about that. I think I anticipated mixed reviews and that’s what I’ve gotten, so maybe not surprising but just kind of what it means as an artist to make peace with the fact that not everything is for everybody. I think in the larger landscape of what I make and am making and have made, this book is going to be a real turning of a corner for me. I hope to be more expansive and more experimental, and ask bigger questions, and untethering myself from some of the public reaction has been really powerful, to just let go of what the hopes are and let the work do what it’s doing.

I really do think of art as a kind of channeling, and with this book in particular, I was doing a lot of ancestor worship. I was doing a lot of prayer. I was calling on folks to let me show up and do the work that is important, and I would sit down and I would write and I felt so tuned in. Then at one point I was pregnant, I had surgery, so many things happened to my corporeal self and to my spiritual self while I was writing this book, and I think that ended up in there. Even the dedication to Ori, which is your higher self, would have been unfathomable a couple years ago. But I think since the day that I wrote that dedication, I’ve really taken the stance that the creative in me, the thing that I’m tied into, deserves this acknowledgement.

So, I’m realizing that not every piece of work has to be the end all be all—every piece of work leads you to the next thing. Adult literature moves differently, and people are looking for things young adult reviewers and readers maybe are more generous with. Once the book is out of my hands it’s yours, and what you bring to it and what it brings to you, that’s great. All I can do is keep working on my craft and continue to be really dedicated to clarity of my vision.

I think adult readers need to read more young adult fiction anyway. But what I also like about the book is that I don’t have to talk to my mom about pornography either. I can be like, “Take this book and read it.” And I know she’s going to enjoy it because part of why I enjoyed it is how close I felt to everybody; there are so many members of our family that overlap with a lot of these characters. It is nice to have someone else be the voice for you sometimes.

That’s one of my big hopes for this book—for all of my books, but this book in particular. Folks sharing it with their tias and their tios and their moms and their nieces and nephews, and having some intergenerational conversations. I think when books can do that it’s amazing. Growing up, I always wanted a way to be closer to my mom, and I couldn’t figure it out, and I think she wanted to be close to me too, but also had her own barriers. I remember buying one book that I found in English and Spanish and giving her that book and asking her to read it while I read it in English so we could talk about it. We didn’t really talk about it, but it was still dope to watch her work through this book. I think the language it can give you, it can offer something so that you don’t have to say the thing.

What are you working on now, or are excited about next?

I am working on both a young adult novel and an adult book, so I am in two worlds. I’m always writing, especially when a book is about to come out. I think I get really nervous, so I channel that energy into the next thing. I began writing these two books right as Family Lore was about to be published. We’ll see what happens with those, but I’m really excited.

I feel like new things have been happening with my writing. I want my writing to feel like you’re entering different kinds of rooms. I think Family Lore allowed me to break open non-linearity and time jumps and many characters. Now I’m taking what I learned from doing that and thinking about how, if I simplify to just one single character, how can I keep playing with time? How can I keep playing with where the welcome mats are? Now here’s a sideways view into a story, and now we’re back to the central story. I love giving access into a story from different directions, and I want to keep playing with that.

I’ve also been engaging with a lot more visual art and going on studio visits and learning about folks’ practice, and I think that’s having a real effect on how I’m contemplating what it means to be someone who makes things. I’m thinking about how to be in conversation not just with other writers and poets but, like, how are you talking about the Dominican Republic? How are you talking about Haiti? How are you talking about the Caribbean? How does that challenge or open up how I’ve been talking about it? And do I have to rethink some of the things I’ve written or where I’ve written from? So, I just feel really open to what’s possible.

Featured Book

-

.

Family Lore

By Elizabeth Acevedo

Published by HarperCollins / Ecco

When Flora brings her family and community together for a living wake, her sisters are surprised. Flora can predict, to the day, when people will die, and they wonder if she has foreseen her own death or someone else’s. In the three days leading up to the wake, Family Lore traces the lives of the Marte women, weaving together past and present, Santo Domingo and New York City, in this indelible portrait of a family full of secrets.

About Elizabeth Acevedo

-

Elizabeth Acevedo

Elizabeth Acevedo

Elizabeth Acevedo is the national bestselling author of Family Lore. She is also the New York Times bestselling author of The Poet X, which won the National Book Award for Young People’s Literature; With the Fire on High, named a best book of the year by the New York Public Library, NPR, and Publishers Weekly; and Clap When You Land, which was a Kirkus finalist. She holds a BA in performing arts from the George Washington University and an MFA in creative writing from the University of Maryland. She resides in Washington, DC with her loves.

Photo Credit: Denzel Golatt