November 29, 2023

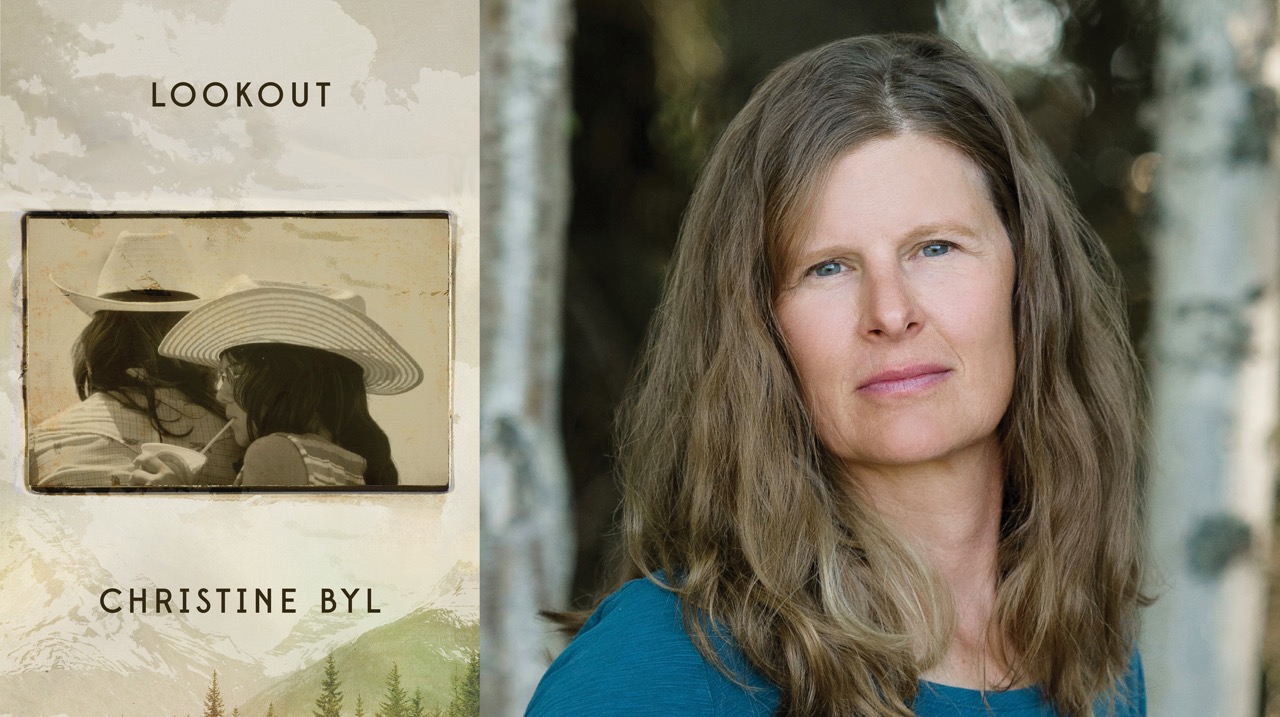

Christine Byl, author of Lookout, spoke with Kait Astrella in celebration of being shortlisted for the 2023 First Novel Prize. The novel is set in rural Montana, where Josiah and Margaret Kinzler have forged an unusual bond marked by both tenderness and distance. Their daughters, Cody and Louisa, grow up watching their parents navigate what it means to be true to yourself and what that costs. This gripping dual coming-of-age story explores a family coming out to itself in a new and nuanced American West.

Where did this book begin for you? What couldn’t you stop thinking about that led you to pursue it across the novel form?

This book actually began as a short story. It’s always interesting to talk about the genesis of this book because the time between that story to the day of publication was approximately 25 years—which is crazy, especially considering some debut novelists are 25 years old. But, it began as a short story I wrote in a workshop with William Kittredge, who is a very influential and beloved teacher and writer centered in Western Montana, with a lot of influence throughout the West. I put it away for a decade, I didn’t think about it. Then I came back to it in the early 2000s, noodled around with it a little, put it away again. Then the last six or so years have been more active drafting in an intentional way toward knowing that it was a novel. I almost think of it like approaching a shy animal; it needed a little sidling up to, patting it on the head, letting it come sniff me, not putting a lot of pressure on it. Although it was frustrating at times during the writing to wonder why it wasn’t happening faster, I feel like the book is better and really couldn’t be what it is without the long living within the characters and letting them change over the decades while I also changed.

I would love to hear about your decision to structure the book in sections. We have some sections in the third-person that hop around in time and other first-person sections in which it feels like the characters are speaking directly to us. We even hear from Jade, the family dog. Why did you decide to tell the story of a family this way?

The first chapter began with the third person that anchors the story throughout every other chapter, and for a long time I thought was just the book’s voice. I’ve always been really interested in multiphonic stories, and I’ve often found that the narrative hegemony of a third person voice can sometimes feel a little bit overreaching, or not really picking up all the nuances of different people’s voices. So, I had always been interested in that more fractured, multivocal kind of narrative.

I found an old short story that I had written at a totally different time than the first one that was written in the direct address that you’re referring to, where the character is speaking in an unfiltered way in their own voice. And something about the character in that story made me think, “Is this the same character as Cody?” They did not have the same name, they were not the same age, they didn’t have the same architecture of their family, but the voice and the relationship between the sisters made me think, “This might be the same sisters.” Once I allowed that in, I thought, “Okay, so, what do I do? Do I revise the content of that chapter and try to put it in the third person?” Then I was like, “I’ll just let it be. I’ll just try writing other characters,” thinking maybe I was doing that in more of an exploratory manner. But eventually it came into a bit of a pattern where I felt like every other chapter there was somebody who could speak in a way that altered the truth or the take-home of the chapter prior, and let in little glimpses of other characters.

It was also partly because a big interest of mine is how our identities are not just who we feel we are, but how we are seen and how we are affected by and affect others. Having lots of voices seemed to me like an honest way to speak about a family, and also about a small town and a community with both the ups and the downs of people knowing you well. There’s an emotional intimacy, and a narrative understanding of each other’s lives, and there’s also sometimes gossip, and sometimes misunderstandings. So, it just felt to me like that was an honest and a useful way to tell the story.

I think to a beautiful effect, for sure. It was a very pleasurable reading experience and it really felt different to see the third-person, more traditional narrative style intercut with these voices. You get the best of both worlds. I would love to zoom way out beyond structure and talk about Northwestern Montana. You spent a lot of time in Northwestern Montana. Could you talk a bit about the rich Western backdrop of the novel and why it is personal to you?

Yes, I often refer to Western Montana as the place where I became a grown up. Even though I grew up in Western Michigan, where I’m from, I feel like my adult self was really born and built in Western Montana. It’s a very evocative and grounding landscape and set of cultures for me. It was the first place that I lived among a labor subculture, with people who worked seasonally and who worked with their hands. That eventually led me into my job, which is trail design and construction. It was the first place that I had lived closely with native Indigenous Americans. It was the first place that I discovered on my own, letting myself be led by an actual landscape. It was a feeling of exploration in a way that I had never had, and I was being mentored by people who knew and loved the place and who had the skills I was interested in. It was just a very formative time. I have a lot of tenderness towards it.

It’s also a complicated place. It’s a locus of the inland Northwest. There’s a lot of conflict and strife around first people and colonialism and genocide and injustice, and there’s also a lot of beauty and human thriving. A lot of the places I’ve loved the most are pretty complicated. I’m in Alaska now, and I’ve been here for twenty years, so I didn’t really start writing about Montana until I left Montana. I don’t think it was so much the removal itself as it was just that time elapsed and allowed me to come back to that place with a little bit more of a grounded and nuanced eye.

You described Montana, the place and the land, rooting these characters, and at the heart of the book is obviously the Kinzler family, Josiah and Margaret and their daughters, Cody and Louisa. Throughout the novel, we spend the most time with Josiah and Cody, who often feel at odds with the world around them. I think we are used to seeing stories of the West in which intrepid families loom large. The girls sometimes play Little House on the Prairie when they are children, for example. Can you talk about how the Kinzlers fit or don’t fit into this kind of American Western canon and this complicated place?

I have loved many of the classics of that canon since I was a kid, starting with Little House and the Great Americans biography series that were set in the West, and moving through to Willa Cather and Larry McMurtry and Cormac McCarthy, and so many others. But as I moved to Missoula and started reading more widely, I realized that the Western has been described in a way that primarily locates the white man vs. nature narrative, a very conflict-oriented narrative. The more I read, the more it really felt resonant to me that the American West is built more on communities and trying to establish connections, whether it’s with land or with people. All of the traditional narratives like a stranger rolls into town, or two families in conflict, or the trapper on his trap, most of those stories we describe as being about conflict and isolation, but the core of so many of them is about a longing for connection.

So, as I read more widely beyond the ‘canon,’ I discovered people like James Welch—an incredible Montana Indigenous writer of fiction, and Molly Gloss—an author from Oregon who writes a lot of women-centered pioneer narratives. There’s just so much good beyond the Wild West writing. And I definitely locate Lookout within that. I didn’t start writing it with the intention to upend the Western tropes, but I think because I believe that the way we have culturally described the West is not always the full story, I find myself always looking for the stories that enlarge it, that crack it open, that allow other people to speak.

That’s why I wanted to write a book set in the West where the main family might be a white ranching family, but they have friends and people they rely on of lots of demographics other than theirs, and those people are citizens of the same space. There are abortions and diseases and fights and drunk teenagers and people who want to get out of there, and all of that to me is just as much part of the West as, you know, roping the cattle and six-shooter action. It’s like any tradition; you have to find out for yourself what do I want to accept from what I’ve inherited in the lineage that I’m from, and what do I want to push on, and what do I want to enlarge.

You named a couple of writers just now, but I’m curious about other books, art, movies, or even music that you feel were really influential in helping you crack open that canon, or just in your writing more generally.

Yeah, a lot of the ones I just mentioned, the old classics. Then, when I moved to Missoula, I read everything I could get my hands on. I mean, you name it: Deborah Magpie Earling, Rick Bass, Bill Kittredge. Annie Proulx was someone I was drawn to again and again, because I found her stories and her sensitivity to characters who didn’t always fit a mold to be quite attuned.

I wanted to ask you about the title, Lookout. It recurs as a phrase many times throughout the book, sometimes as a warning, sometimes to describe a vantage point as in “look out over,” sometimes as the literal position in a fire squad. Could you talk about the significance of that phrase for you?

The title came quite late. My husband is actually my titler. I never can seem to settle on a title. I have to brainstorm a lot to get one, and I went through so many clunkers with this novel. I am really drawn towards words that hold meanings in tension, sometimes even opposite, like the things you just mentioned. Shouting “lookout” can be a warning. It can be a game. It can have a sense of fun or protection. A lookout on a fire crew is someone with a long view; they’re looking over the whole scope of everything, but they’re also paying attention to tiny details. A lookout on a perimeter to me has the feeling of both watching to see what’s incoming, as well as protecting what’s inside. All of that converged in that little word and it just felt right to me.

When Margaret is expressing regret about not visiting her brother in San Francisco she says, “Don’t ever be afraid of someone else’s life.” And yet, the characters in the novel often harbor secrets and fears about their own lives. What drew you to this very human contradiction? That willingness to accept others but a difficulty in navigating or articulating the self?

I have certainly navigated the tension in relationships of wanting to be close and to also want to protect myself, and I’m sure others have too. Sometimes that is not so much a fear of vulnerability, but it’s having to coach yourself to remember that vulnerability is worth it. Humans and families can be very painful, and there can be all kinds of misunderstandings and traumas and fear of each other that I think rightly sometimes keep us from intersecting. So, I’m interested in the ways that humans, within families and among animals and places, can become a fuller version of themselves by allowing themselves to be beckoned there by others.

I think there’s another part of it that’s related to the setting that you were noting earlier. I have always thought of places as characters. I remember when I was young, learning about the parts of the story and the dramatic arc and the characters and the setting and the dialogue and all that. I remember having a kind of dissonance about why the setting was not considered a character. Why wouldn’t a place as big and intense as the one in which this book is set be a character? And I feel like the people in the story are the most free or the most vulnerable or the most daring when they are in relationship to their place as well.

There’s a lot of very elemental experiences that the characters go through in this book. Cody ends up becoming a firefighter, and fire features in the novel from the beginning, when Josiah demonstrates the danger of playing with matches by setting a fire on purpose. Cody remembers that later and thinks, “No matter how well you knew it a fire could surprise you.” I think that also applies to people. Could you talk about how the novel explores the unknown combustive potential in the people we think we know well? You said you were interested in the way identity is constructed not just by how we think of ourselves but how we’re perceived.

It’s really interesting to hear you say that, the combustive properties of being people. I teach chainsaw classes, in my other profession, and we talk a lot about how, when you start an engine, the properties that are required are fuel, air, and spark, and any time you’re troubleshooting you go back to that. Is there fuel, is there air, is there spark? So, what would those components would be on the human level? I think there’s a constant kind of movement in human relationships between aloneness and self, between relationship and others, and maybe we create a third self between all of that. And that creates a degree of combustion. Just like too much air will put out a fire, too much aloneness will extinguish a relationship, or sometimes you need to fan on the flames to tend to something more vigorously.

How did this family come to take shape for you? Do you feel like you heard voices for the characters, or was it tied to what your writing practice is like? By the end of the novel, from all the ways that we’re hearing from them and seeing them from the outside, they feel so real.

I like that you mentioned voices, because I’m a pretty voice-driven writer in general, and because this story has so many direct address voices in it, that was definitely a huge part of it. The kernel of the story started as I was learning about the West and about fire season—the practices of firewising your property, having a cut space so that you don’t have trees too close to something that could burn, or the kind of precautions you would take with things like starting a chainsaw or having a campfire or backpacking with a stove. The story about Cody and her dad lighting the perimeter of a very contained flame—the backburn or the black, which is a perimeter of something that has already been burned so there’s no fuel there—something about that very technical space and technique, combined with the intimacy of the trust and also the reprimand between a parent and a child, really drew me in. So, I wrote that scene, and then the characters grew from there.

I would say that the book’s development was very much anchored in hearing the characters’ voices— hearing them speak for themselves and hearing what they didn’t say. My process is pretty unusual for a writer in the sense that at least six months of the year, I’m in full throttle construction season. I don’t have a morning pages practice or a disciplined schedule. When you work ten hour days of outside labor, you don’t have time at night, you don’t have the energy to be like, “and now I’m gonna work on my novel.” At least, I didn’t. But I had so much time for talking to myself inwardly, where I would have dialogue just flowing, trying to imagine what people would say to each other or what they might think. And because I was working in the woods and in a forestry setting, like my characters, I would have times where I would be with a coworker and I would think, “Oh my gosh, that’s exactly what Josiah would say,” and I would introduce it into a character. So, not only was the book driven by the voices of the characters rising from within my process, but it was also shaped by the voices from within the West that I internalized and let shape the story in ways that I don’t think I necessarily would have thought of on my own.

That’s wonderful. There’s a really good essay by Durga Chew-Bose that talks about a litany of things that she would consider writing, like laughing with a friend or touching a loved one on the back of the neck, just like serious noticing. I was curious if you had any stumbling blocks when you were writing this novel? I know it took a long time to write, but were there any major hurdles that you ran into when you were trying to chart the story?

Something that took me a while to unravel was, once I committed to the structure of the voices changing roughly every other chapter, I then had to figure out another,like, fifteen narrative chapters. I had five or six that occurred very easily, and then I had to figure out what other voices I wanted to amplify in the story. But I didn’t want them to be forced, I didn’t want them to feel like I was making the characters say something for a certain end. In the more serious last six years or so of working on revisions, I was allowing those speakers to come to light in a way that wasn’t me just moving characters around, because I don’t like to feel like the characters are chess pieces. I had a few times where I felt like I was doing that, and I had to put the book away and be like, okay, I gotta wait until these people are ready to speak for themselves. That allowed some of the more auxiliary characters, like a neighbor or a client or a doctor, who weren’t in the family but had a vantage on them, to show up and surprise me in a way.

Another issue that I wanted to be really attentive to was that I wanted to write a book about a family who is white that wasn’t in only a white world, because that’s the West that I know and the way that I grew up. I have a white locus of experience, but my life has not always been full of only white people, and I find books like that to be very frustrating. I wanted my West to be populated with people who were in the Kinzler’s world, but were not just like them, but I didn’t want to write in a way that was tokenist or that was moving people around on a chessboard in order to check some box. It took a lot of patience and listening to where people might show up, and how to speak on behalf of, say, Louisa’s husband, who is a Blackfoot man. I wanted to show him as a full character, but not speak for him. Finding ways in which I could show him as he related to the people who I knew deeply, and I could be respectful of his experience and his difference and his likeness, but not speak for him, took some honesty on my part. I wouldn’t even say it was a stumbling block, but it was something I really wanted to be attentive to. I made myself really slow down and double, triple, quadruple check, knock on them for the soundness test, not just let them come out the way they did the first try.

Now that your first novel is out in the world, what shape is the rest of your work taking these days? What can we look forward to in the future?

I’m definitely in that strange space still, especially because this was such a long haul, where I feel like I’ve lived with these people and now other people have a relationship with them. That’s been a combination of excitement and, I don’t know, grief feels a bit dramatic but a little bit of a sadness that it isn’t really just mine anymore. It’s not my own family and world. So, I haven’t thrown myself fully into something new. I have a collection of essays I’ve been poking around at for a long time as well, so we’ll have to see what arises, but I do know I really love books that are written in conversation with each other, but not exactly sequels. Like the one that comes to mind the easiest is My Name is Lucy Barton by Elizabeth Strout. She has four or five that are all about characters in the same world. Marilynn Robinson’s Home trilogy is another one. I love the idea of coming back to this same world in a different way, in a way that almost upends what is already written. So, that’s something I might play around with. I also have a bunch of novel ideas that are, like, completely hairbrained. The kind you don’t even want to say out loud yet. We’ll see!

Featured Book

-

.

Lookout

By Christine Byl

Published by Deep Vellum / A Strange Object

In rural Montana, Josiah and Margaret Kinzler have forged an unusual bond marked by both tenderness and distance; their daughters, Cody and Louisa, grow up watching their parents navigate what it means to be true to yourself and what that costs. This gripping dual coming-of-age story explores a family coming out to itself in a new and nuanced American West.

About Christine Byl

-

Christine Byl

Christine Byl

Christine Byl is the author of the novel Lookout and the memoir Dirt Work: An Education in the Woods, a book about trail crews, tools, wildness, and labor; it was short-listed for the Willa Award in nonfiction. Her prose has appeared in Glimmer Train Stories, The Sun, Crazyhorse, and Brevity, among other journals and anthologies. A grant recipient from the Rasmuson Foundation and the Alaska State Council on the Arts, and winner of the Alaska Literary Award in 2015, Byl has been a fellow at Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference and writer-in-residence for Fishtrap’s Writer-in-the-Schools program. Christine has worked as a professional trail-builder for more than twenty-five years; she lives with her family in Interior Alaska on the homelands of the Dene.

Photo Credit: Dori Yelverton