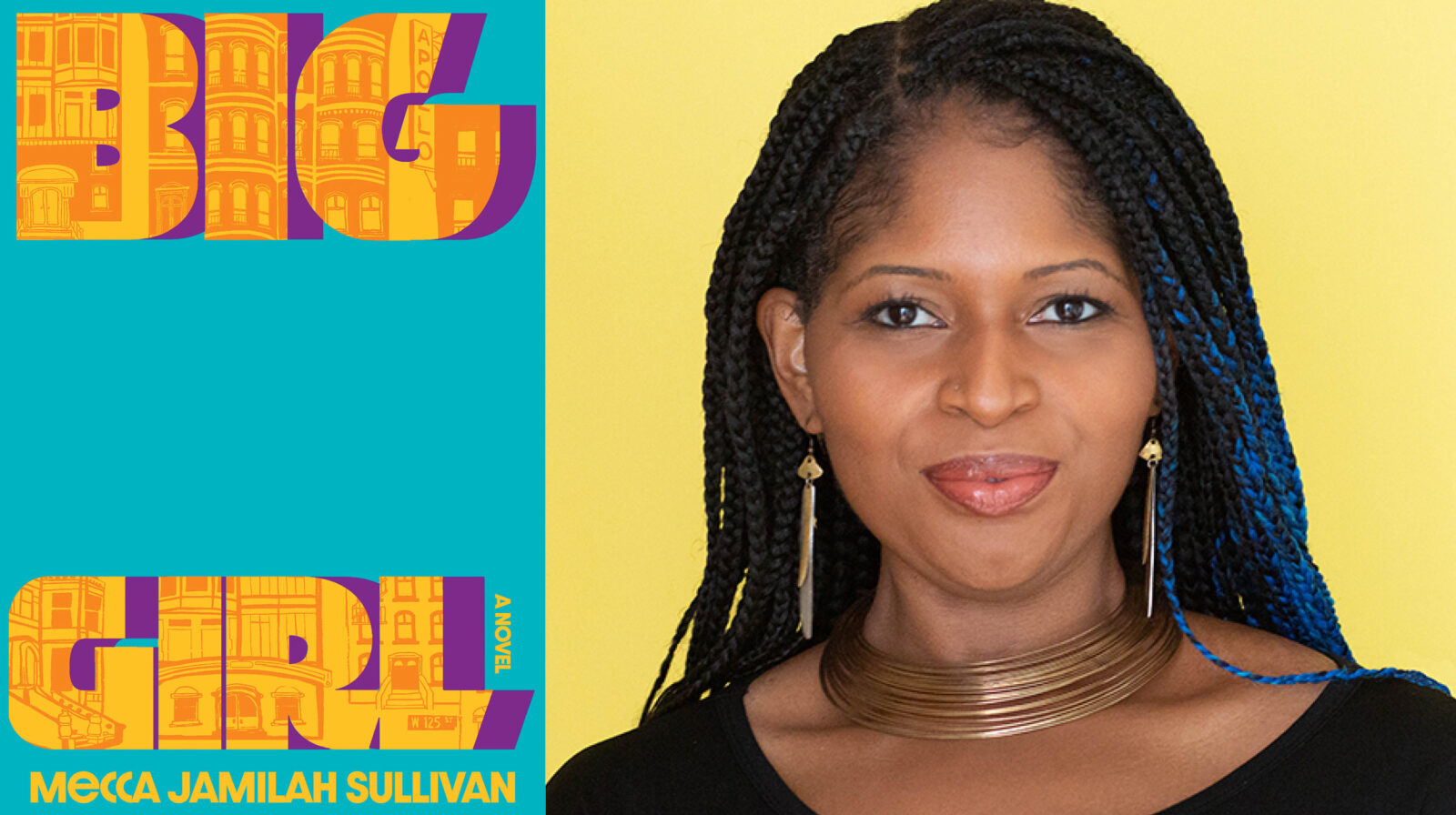

Mecca Jamilah Sullivan, author of Big Girl, spoke with Melanie McNair, The Center’s Senior Director of Public Programming, in celebration of being shortlisted for the 2022 First Novel Prize. In this novel, an eight-year-old girl in the rapidly gentrifying Harlem of the 1990s struggles to suppress her insatiable longing in the face of her mother’s conscription into diet culture, pressures to fit into a narrow definition of femininity, and her outsider status in a predominantly white Upper East Side prep school. When tensions at home culminate in a family tragedy, she is forced to finally face the source of her hunger on her own terms.

What was the first seed of this story?

This story has been with me really all of my writing life and, in some ways, all of my life more broadly. I discovered really important coming-of-age novels about Black girls and Black women when I was my main character’s age. I was eleven years old digging through my mother’s library, reading Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye, reading Ntozake Shange’s For Colored Girls and Sassafrass, Cypress & Indigo, reading Jamaica Kincaid’s Lucy. All of these were novels that were not written for people my age and yet it was really important for me at that age to see that a young Black girl’s life was something that can rise to the status of literary importance, and that writing about those lives is something that one can do for the rest of their life. This is a career path and artistic vocation. So, realizing both of those things early on inspired in me a need to continue to see stories like mine represented. As much as I connected to those novels and still do to this day, the specific experience of growing up in a fat body and seeing the meanings of that body vis-à-vis the people around me was such an important, profound part of my experience of Black girlhood and Black womanhood. So, from very early on I realized this was something I wanted to write about.

You do it so well. There’s just so many layers in this book. Who did you imagine your audience would be for this book?

I definitely felt a profound sense of needing a novel like this, and so I feel as if I’m writing for those who need this novel, for those who need to hear this voice. But, honestly, I feel as if that’s everybody. I think that everybody needs to hear the voice of a character like Malaya Clondon and hear the critical perspective of body shaming, of fatphobia, of racism, of sexism, of heterosexism, and all of the experiences that Malaya has. It’s from her perspective, but to me that’s a critical voice for all of us to be paying attention to.

Absolutely. Are there any other books about young fat girls that you’ve read?

One that kind of comes to mind most readily is Push. That was an important novel for me as a teenager. There have been several others, and those novels have been influential for me, but I will say because I started conceptualizing this novel when I was very young, I was thinking about what this novel would be before I had the chance to read some of those other novels. I feel as though I grew up with this character before it became a character. There were journal entries, there were short stories; this has been an organic process for me growing as a writer along with this character in the process of developing this novel.

What were your biggest challenges with writing this book?

Honestly the biggest challenges were pragmatic, they were logistical. Like I said, this novel has been with me and been on my mind and on my heart pretty much as long as I’ve been alive and as long as I’ve been a writer. And yet, in the interim, I was finishing my undergraduate degree, then went and got a Master’s in English and Creative Writing and a version of this was my Master’s thesis, and then I thought okay I guess I’m going to get a PhD because I enjoy teaching. I wanted to read more, and I knew this would be kind of a way to spend my time that would feed the novel. I thought I’d just work on the novel on the side, but of course I came to find out that’s just not how PhDs work. It was definitely a challenge to make space for the novel and carve out time to really invest in the novel. Then doing the PhD meant writing a dissertation, which meant once I started teaching on the tenure track that meant turning the dissertation into a book. I was trying to stay active as a creative writer while all of this was happening. I was writing short stories too and those stories became my first collection, But, yeah, the biggest challenge in writing this novel was continuing to prioritize the novel beyond my emotional commitment to it while living life, writing other books, and focusing on other aspects of my career.

I was wondering what was the most drastic change from the first draft of the story to the final. Since you’ve been working on it for so long, let’s say from your thesis to the finished novel, what was the biggest change if you could tell us without spoiling anything?

I was just thinking about this the other day. There was a drastic change in length. The first draft was about 500 pages, so I cut a whole lot, which is of course hard to do. Those changes happened in stages, though. There was one big section that got cut that made the novel a lot tighter, but there was also a major shift in point of view. The original draft, the novel actually shifted between the point of view of four major characters—Malaya, her father, her mother, and her friend and companion Shaniece. It was pretty much the last significant revision. I decided to just experiment with focusing only on Malaya’s voice, which is what I had to tell myself at first. But it turned out to be the right thing for sure. I realized there was a way to really root the reader in Malaya’s subjective experience of her body, but also of her imagination, of her emotional life, and that was actually the strongest position from which to issue Malaya’s critical perspective on the world around her.

That’s really interesting too because there’s so much depth to all of the characters that you have. Do you think it’s because you knew them so well too?

Yeah, totally. I think in some ways those earlier chapters in the other perspectives were character studies. Some of those scenes exist in the finished novel rewritten from Malaya’s perspective, and I think that was an important exercise in building those scenes. For example, there’s a scene where Malaya’s at a doctor’s office with her father and the father is conflicted about being at the doctor’s office to begin with; what it means to care for his child’s body is something that he’s thinking through a lot. It was really important for me to be in that scene from his perspective so that I could find smaller, more nuanced ways to show his inner conflict once it came time to write it from Malaya’s perspective. It really helped me to depict those scenes as fully as possible and with compassion for all the characters.

There’s so much compassion for the characters, and each voice is so distinct. You have such a talent for dialogue. What would you tell young writers about writing dialogue the way that you do?

I appreciate that, thank you so much. I do encourage my students to do listening exercises. In my classrooms—especially my creative writing classrooms, but even my lit classrooms—we try to approach reading and writing and thinking as connected acts that are always embodied. I have exercises where I encourage my students to go into public spaces and listen, listen to the human voice, listen to people’s cadences and rhythms, and seeing how they can isolate sound patterns before we get to language. Then listen in a different way and think about what kinds of words you can hear and jot some of those words down. Then we’re finally isolating a voice, and using that voice to create a character.

I’m definitely a voice-driven writer so voice is most often the first thing that comes to me. Part of it is also learning to trust the voices that come to you as a writer, and getting curious about those voices so you can follow them to other elements of the fiction like character or plot or even setting. It’s great to hear that that’s coming through for you as a reader, it’s definitely something that I think about a lot.

I’m sure this changed over the span of time you were working on this, but what was your writing practice like once you got fully back to working on the novel?

I admire those writers who get up every morning and devote a certain number of hours or pages or words to whatever their creative project is, but I haven’t had the flexibility to really be able to do that. So, my practice has been seizing whatever chunk of time I have between semesters, or between exams, or at one point in between finishing chapters of my academic book. Then I would come back and say, okay, I have two weeks that I can focus on this novel, or I have two days that I can focus on this novel. It ended up being a matter of clearing time so I could immerse myself as much as possible in the world of the novel again. Sometimes it was months before I was able to do that. The pandemic actually gave me solid time to do a final read through and do some reorganizing and fine-tuning before my agent and I felt it was ready to go out, and I was grateful for that time, honestly.

When you have breaks of months at a time, is it like you have to grease the wheels a little bit to get back in it, or was it such a passion that you were able to dive back in?

I’m inclined to say the latter. These characters have been with me for so long that even when I’m not writing about them I’m still learning about them, I think about them often, and that’s been the case before I even started working on the novel. So, in that sense I’m grateful to say it hasn’t ever been hard to get back into the world of the novel or reacquaint myself with the characters. Sometimes I did find that trying to reorient myself to whatever problem I was trying to solve last—for example, the question of structure and point of view—there were some times when I’d come back and I’d have to remind myself why it made sense to, say, focus on Malaya’s point of view. I was so invested in these other characters that it took a while to get back to that vision. But, even then it wasn’t too much of a challenge. Part of it honestly is because my time was always pretty finite and pretty limited, so I had to get down to business even if I wasn’t totally sure of what I was doing and just trust that eventually that vision would become clear again.

So it really does require a certain sense of faith. That’s something that you can’t teach, right?

It’s true, but it’s something you can learn. My hope is that’s something you can see happen with Malaya as well—that trusting oneself, trusting one’s desires, one’s impulses, one’s inclinations towards pleasure and joy. That’s definitely what she’s working to learn in the novel. I think I had a similar process in terms of really trusting my creative voice, trusting my creative vision, trusting my commitment to this novel even as my career went in all of these other ways.

This is such a big question, but what are some of the larger conversations or topics that your book speaks to or engages with? I feel like there are so many.

I hope so. I think probably the most salient one is the conversation about fatphobia, body shame, body shape and size, and the stigmatization of bodies. Of course for me that conversation is inseparable from conversations about gender, race, class, sexuality, ability and disability, and all of the ways in which the social structures of the world really limit the freedoms of certain bodies. There’s an elaborate latticework of customs and opinions and attitudes and structures that do so. My hope is that Malaya’s experience of her body is both an intimate interior experience of coming of age, and a reflection of the interconnectedness of several of these structures as they impact this character and the experience of her body. There’s something really moving to me and interesting to me about thinking about intersectionality, global power structures, these big difficult concepts, through the experience of this little girl who is perceptive but doesn’t have any of that language yet. All she has is her feelings, what she experiences. For me that’s something that coming of age literature really affords us in terms of a larger social questioning or critique that I appreciate.

Something else that you do so well is writing about shame, but in a way that’s balanced with healing and humor and insight. What would you say to aspiring writers about writing about shame, or people who are writing about the power systems that you were just talking about?

My approach is about paying attention constantly to nuance and complexity even when it feels awkward or incongruous. The moments where there can be intense experiences of pain or shame often somehow have humor that pokes through, which can create additional conflict where you feel like you shouldn’t be laughing. Or, you recognize that this person is saying something mean and cruel but maybe there’s a song playing out the window that makes you feel good at the same time. So, pay attention to one’s own life or in your reading for this simultaneity of seemingly conflicting emotional experiences.

Sometimes I think in narrative there’s a tendency to try and organize the emotional complexity of life, to streamline it, thin it perhaps to something that feels coherent and stable and linear, but I don’t think that’s the way that emotional experience tends to be. In the case of somebody like Malaya, she is always looking for pleasure, and part of why she’s always looking for pleasure is because she’s being educated in shame. She’s being taught not only to be ashamed but specifically how; here is exactly how you access the proper sense of womanhood, by being ashamed of each of these aspects of your life, your body, your desire for food, your relationship to touch. Malaya has to go out of her way, she goes on a fact-finding mission, to access other modes of pleasure.

As a writer, there’s a similar thing that I found myself needing to do, looking for where Malaya finds her pleasure, where she finds her joy, and really allowing her to experience those feelings as profoundly and ultimately maybe even more profoundly than she experiences the simultaneous moments of trauma, of pain, of rejection, of denial, of policing. That’s how she survives. All of this rings true for me in life as well.

Since this is your debut as a novelist, what do you hope this book says about you as a writer?

I appreciated when you mentioned compassion. I hope that this book says that I’m a writer who’s really invested in the emotional complexity of my characters and understanding my characters with a sense of compassion, even as there’s also a need for critique.

What more can we expect of you in the future?

Lots more writing, hopefully. They say god willing and the creek don’t rise— I hope to keep writing with these themes of gender, of sexuality, of bodies, and how they impact the relationships between people, specifically people of color and queer people over generations. They’re themes I imagine I’ll probably always be deeply interested in. I also think there will be some more formal exploration. My short stories are kind of experimental, and I look forward to playing with form even more in the future.

I want to talk a little bit about Harlem because it feels like it’s another character in the book. What is your relationship with Harlem, and Malaya’s relationship with Harlem, and why is it so central to this book?

I was born and raised in Harlem. It has always been an important part of who I am and how I understand myself both as a person and also as a writer. It’s a neighborhood with such tremendous literary history and a broader cultural history. For me, being a teenager in Harlem in the ‘90s, the music I was hearing and listening to and memorizing like teenagers do is as much a part of my literary influence as those novels I mentioned earlier. Biggie, for example, is as much of a literary influence for me as a Toni Morrison, and that is something I attribute to Harlem. Hip hop, especially by now, is absolutely global,, but having that experience of a community around hip hop—especially as someone who, like Malaya, went to school in the Upper East Side and not Harlem—was important. The storytelling strategies of hip hop and of course the fashion, the color, all of those experiences of the neighborhood really shaped my sense of a creative artistic vision.

I think something similar is true for Malaya. For her, her experiences of the gentrification of Harlem, and the changing landscape of Harlem, really offer her a mirror for her own transformation, her own growth process, her coming of age process. Observing and connecting with Harlem helps Malaya understand change and process loss so that as she’s experiencing different forms of loss in her coming of age process she sees the neighborhood also experiencing loss, but simultaneously finding ways to retain aspects of its core self, finding ways of fighting against the destruction of its core self. I think she finds a lot of inspiration and, maybe more importantly, comfort in that. She’s less alone because of the neighborhood, and that’s something that’s meaningful to her and certainly meaningful to me as a writer.

I don’t know who said this, I tried to look it up, but somebody said that all writing is writing about grief, and there’s a lot of grief in this book. You talked about the changing neighborhood in Harlem, and then the coming of age grief—which I haven’t really thought about as part of the process but of course it is, there’s so much change that happens, and there’s always loss with change. Did you know that grief would be a part of the book when you set out to write?

No, I really didn’t. On a certain level I knew that trauma would be. I knew that the core experience that Malaya’s having is a traumatic one, so I knew I would be figuring out a way to convey that traumatic experience while also conveying the joyful pleasurable experiences that she has, but I didn’t quite know how grief would figure in. There are a lot of losses in Malaya’s life, not only literal losses but also the loss of relationship to food that is guided mostly by pleasure. When we first meet Malaya she’s like, “I love French fries, they’re the best, I refuse to let anyone steal the joy of French fries from me.” She’s got this very full innocent insistence on her own pleasure. I hadn’t thought about the trauma of losing that as a process of grief in a way. It was really learning from the character, realizing as her relationship to food changes we see her relationship to her family members change. There’s a loss of joy for her in a certain sense and yet she’s constantly on the lookout for other forms of joys. Sometimes she finds them and sometimes she doesn’t, but that becomes her way of coping with those kinds of grief.

There are other moments of grief narratively, more specific losses in the novel, that truly happened as I was writing. Those are the funny kind of weird moments as a writer where I let my characters guide me. I hadn’t planned on them being a part of the narrative but every time I tried to write past them, I couldn’t. Now I understand too that she had to experience a loss that no one can attribute to her own desire, that no one can blame on her, essentially. From these losses she’s finally able to see that there’s actually, as much as she’s always told that she’s the biggest thing in the room, something much bigger than her in the world. There are many things much bigger than her in the world, and while that itself is another cause for grief, it also frees her to be different and to let herself be bigger and not be afraid of the impact that she might have on the world around her.

Something else that I loved is the way that you bring in all of the senses in your writing. I could hear Harlem, I could totally feel the grease from the French fries on my fingers, the smells, everything. You really put it all on the page in a way that I feel like few debut novelists are ever able to achieve. How did you get around to that, what do you say to your students about writing using all the senses?

Thank you for that. As a reader, I do think that reading and writing are both bodily experiences. We don’t often think of them as such but they are. We all know that feeling when we’re reading something and you feel it in your gut or in your chest, and that happens for me as a writer as well. So, rather than try to sublimate writing to a purely heady intellectual space I try to pay attention to the body as I’m writing. Of course, most of my characters have a particular and important relationship to their bodies. I try to stay in their bodily experience as I’m writing them, even when I’m not in a first person. I’m constantly imagining what is happening not only in space but within the character’s body and honestly I find those to be some of the most enjoyable writing experiences. Some of my characters’ bodies are similar to mine— I have lived in a body similar to Malaya’s—but some of them are totally different, so it’s a really interesting imaginative act as well.

This is something that I absolutely encourage my students to do. I have an exercise that I give students, especially when they’re writing something that feels familiar either because it’s semi-autobiographical or because it’s a draft that they’ve sat with for a long time. I often encourage them to change one physical characteristic about whatever character they’re writing and try to re-encounter the world through that slightly different body. That is a way of bringing them back to the body as possessing a kind of knowledge that we often don’t focus on, but it’s literally always with us and we always are learning through our bodies. So, that’s something that I try to do in my own writing as well.

What has the feedback been like for this book? Did anyone react to Malaya and her experiences in the way you’re unpacking in the book, that’s she’s too much?

I’ve gotten a lot of intense, enthusiastic feedback of various kinds. It’s really heartening and gratifying to see that the novel means something to people. I’m now in the amazing stage where I’m hearing from people I don’t know who are sending me these beautiful emails explaining to me why they needed the novel, and I feel like I cannot possibly fully state how meaningful that is to me. I have had other experiences where I hear from people about their own stories of their trauma, especially related to food and body size and body shame, and it can be difficult to hear these stories over and over again, and hearing people talk about their continued hatred of their own bodies, and continued frustrations with their daughter’s bodies.

What’s so interesting is my experience with the people who didn’t think they were going to relate to the book but did. They’ve been like, oh, I related to this because I play football and I have to make sure I stay at this weight, or when I’m not at the gym enough I feel bad about myself. That connection with the novel is often not articulated in the same kind of nuance or with the same kind of depth as people who have more similar experiences to the characters, but it has really been very surprising and eye-opening that that little shred of connection often overrides other kinds of criticisms. It speaks to what we were talking about earlier that this is intersectionality, this is how structures of power connect and overlap so that we’re all affected by them at the end of the day. And I do believe that literature has the power to break through and inspire or at least ask people to rethink their own relationships to power.

Featured Book

-

.

Big Girl

By Mecca Jamilah Sullivan

Published by W. W. Norton & Company / Liveright

Growing up in a rapidly changing Harlem, eight-year-old Malaya hates when her mother drags her to Weight Watchers meetings; she’d rather paint alone in her bedroom or enjoy forbidden street foods with her father. For Malaya, the pressures of her predominantly white Upper East Side prep school are relentless, as are the expectations passed down from her painfully proper mother and sharp-tongued grandmother. As she comes of age in the 1990s, she finds solace in the music of Biggie Smalls and Aaliyah, but her weight continues to climb—until a family tragedy forces her to face the source of her hunger, ultimately shattering her inherited stigmas surrounding women’s bodies, and embracing her own desire. Written with vibrant lyricism shot through with tenderness, Big Girl announces Sullivan as an urgent and vital voice in contemporary fiction.

About Mecca Jamilah Sullivan

-

Mecca Jamilah Sullivan

Mecca Jamilah Sullivan

Mecca Jamilah Sullivan, Ph.D. is the author of the novel Big Girl, a 2022 most anticipated pick from Vulture, Ms, the Root, Goodreads and SheReads.com. Her previous books are The Poetics of Difference: Queer Feminist Forms in the African Diaspora, and the short story collection, Blue Talk and Love, winner of the Judith Markowitz Award for Fiction from Lambda Literary. She is Associate Professor of English at Georgetown University. A native of Harlem, she currently lives in Washington, DC.

Photo Credit: Kathryn Raines