Critically acclaimed Iranian writer, Amir Ahmadi Arian discusses his English-language debut Then the Fish Swallowed Him with world-renowned filmmaker, photographer, and visual artist, Shirin Neshat.

• Purchase Then the Fish Swallowed Him from Our Online Bookstore

• View Shirin Neshat’s Work

I want to begin by congratulating you for this book and saying that I enjoyed it tremendously, though it was sometimes very painful for me to read because I am by nature an optimist, and there are very dark moments. My work is very, very dark as well and always leading toward some light. And I felt so much empathy for the characters. This is something we don’t think about, the inner life, the psychological status of prisoners, but it is something very real for the hundreds and thousands of people that have been in prison in Iran and elsewhere, including people that that are not as lucky as Yunus to be only released in four years, but spend a lifetime in prison or are executed after years there. So I felt like the least I could do is feel the pain of this person, but also the transformation and the different psychological states that he went through. And the greatest value of the book may be that although it’s very specific to Iran, you really manage well to transcend the locality. And I think that’s what makes a great novel about, that it tells the real human story across these divides . . .

Yes, actually, a lot of my sources were accounts by people who spent time in solitary in the US, in the form of books, documentaries, etc. Solitary confinement is practiced very widely and very aggressively here in the United States as well, and it’s much better documented than Iran.

I’d like to ask you to talk a little bit about your personal background, but before that, did you write this novel in English or in Farsi?

In English.

And the biggest question I had when I read this book: Have you ever been in a prison yourself?

No, I have not. But I have too many friends who have been. To give you a timeline of my background: I was born in 1979 in Ahvaz, a city in the south of Iran, and grew up there during the Iran-Iraq War, so my first eight years were lived practically in the war zone. Then, when I was 17, I moved to Tehran for college. I studied engineering at the University of Tehran, but I never worked as an engineer. From the beginning I worked as a journalist and writer. My college years coincided with the reformist movement and the rise of Khatami, which created a politically rich and dynamic environment on campuses at the time, especially at the University of Tehran. Being there at that time motivated me to get involved in writing and journalism and translation. I worked in Tehran for about 12 years. Then the Green movement happened in 2009, and like pretty much everyone in my generation I actively joined it and was very invested in it. At the time I had no doubt that the page has finally turned and we’d have a better future. But it was crushed brutally and thoroughly. Many of us ended up in jail, some of us, like myself, lost their jobs and got persecuted. When life became too hard to sustain, I left for Australia to do a PhD in comparative literature.

How did you get this command of English?

I was born right after the revolution in Khuzestan, and my dad worked for the national oil company. As you probably know, before the revolution everything in that environment happened in English. My dad’s bosses were all American and British, and he studied in the U.S. himself. I didn’t have any kind of formal education in English, didn’t go to any classes or meet an English speaker. But, probably out of the habit my parents carried over from the Shah period, we watched a lot of American TV shows, picked up by roof antenna from Kuwait and Bahrain TV channels. There were also a bunch of English books in our house. I don’t know why or how they got there because no one ever opened them. I started reading them since they were just lying around, and I was a bookworm from very early on, and in the Ahvaz of the 1980s and the 1990s there really wasn’t anything else to do. So I kind of groped my way through English, learning it without having any intention of learning.

Can you speak about how you came to develop this narrative? This is not your first novel, right?

No, it’s the first one in English. In Farsi I’ve published two novels. In 2005, which is the year when this novel is set, I lived in Tehran. If you remember, at the time the bus drivers’ union staged a huge strike.

Oh, yes.

I lived in the west of Tehran, in Shahran area, not far from the bus terminal. I remember very vividly that when the strike took place, the west of Tehran looked absolutely apocalyptic. It was totally shut down because buses were the main means of transportation. I was really impressed by the power the union had exhibited. I’d never seen anything like that, a political move that could disrupt the flow of everyday life in the city so effectively. So I became really curious about how the union worked, how they organized the strike, and who were the people involved in that organization.

Then there was another thing, an image from a news article I read online somewhere. When I started researching for this book I tried hard to find it online but it’s probably gone now; the internet in Iran at the time was very basic. According to that piece, during the strike the government brought some of their own people, strike-breakers, to get the buses out of the terminal. One of them tried to drive a bus out of the terminal and a woman lay down on the ground in front of the bus, which I have recreated in the first chapter of this novel.

I remember that, yes.

That image struck me so deeply and stayed with me through years. So it was a combination of that particular image and the experience of living in Tehran at the time and witnessing how a workers’ union can change the course of everyday life that inspired this novel.

That is fascinating. I found myself very interested in the character of Yunus. To me he seems so unusual and not a typically traditional Iranian man, first of all that he’s not married and that he ended up having an affair with his friend’s wife, but also that he’s such a solitary, lonely man. For the longest time I really wondered whether he was politically motivated or he just showed up at those meetings, whether he was an ideological person or not. And whether Saeed is forcing him to admit to things that he never did. Can you talk a little bit about how you developed Yunus’s character in a way that, for me at least, seems not quite the typical Iranian male?

I actually know a lot of men who live like that.

Keep in mind I haven’t been to Iran for a long time.

I mean especially people who were his age. They were born in the ’60s and were teenagers when the revolution happened. As young men and women they lived through the Iran-Iraq War and what was basically a regime of terror domestically on all fronts. This is an extremely traumatized generation. They got it from all angles.

I also wanted to ask you about the interrogator because it just turned out that a couple of days ago I got the copy of the film with Mahtab Servati, “There Is No Evil” – have you heard about it? Have you seen it?

No, I haven’t yet.

In a very strange way for someone as Mohammad Rasoulof is himself, it humanizes people who are interrogators, or people who are jalad, the executioners.

Right.

In Rasoulof’s film, in all four stories he goes into depth studying both the victims and the victimizers. At some point we begin to identify both with the prisoners and those working for the prison systems, who are strangely tragic themselves while quite evil. After watching Rasoulof’s film, I returned to reading some chapters of your book. And I found so many parallels. I was wondering if while building the character of Hajj Saeed, the interrogator, whether you had in mind that in fact both Yunus and Saeed were both corrupt and innocent, and even equally victims?

Yes, victims is closer to what I had in mind. It’s a novel about a system, not about individuals. It’s about a procedure. Hajj Saeed is primarily following a protocol that’s already in place. He doesn’t really actually add much to it. If you talk to a number of people who have been interrogated in Evin, you will be able to detect certain patterns.

So, yes, I think it’s extremely important to humanize the other side of the story, and for political reasons. If you look at them as absolute evil, you’re basically stifling any attempt to defeat them.

But at the same time it’s a little problematic because we all have choices to make, right? We have morals, we can choose to be evil or not, no? I think that’s what’s interesting. I don’t know, I don’t have the answers because maybe in certain cases the economic situation puts you in a place where even being evil becomes something quite comfortable —

Yes, but portraying them as human beings is different from sympathizing with them, isn’t it?

Yes, yes, of course.

So I have no sympathy for Hajj Saeed, the character. I just try to understand the patterns and the process according to which he operates, and also where he comes from ideologically. It is also important to put both of these characters in the political context of this time period. Because they are not talking in a vacuum. There’s the context of Iran in early 2000s and the emergence of Ahmadinejad and the sanctions and the failure of reformism and everything else that is going on around them.

Yes, and Evin has been a notorious prison during this Islamic Republic or Iran, but we can’t forget that also during the Shah, there were those nightmarish stories of people, students being tortured, and the way they killed the Communists. So this is something you cannot attach only to a specific system or period of Iranian history. Even the American government has taken a similar approach in Guantanamo Bay. So in many ways your novel is about how all prison systems are imposing, injecting suffering and pain on people who either committed crimes or politically opposed the system, right?

I would even go a little further and say it’s also about bureaucracy, the cold-heartedness and the brutality of bureaucratic systems, how they look at human beings as cogs in their machines. A prison is a part of the state bureaucracy in Iran, among other things. That is why, if you know first things about Iran, the plot of this novel is actually pretty predictable. Someone is arrested during a strike, ends up in solitary, interrogation follows, then a kangaroo court with no fair trial, then a bunch of years in prison. And predictability is the inherent quality of bureaucracy.

It’s interesting because one of the books that really made a great impression was on me was Shahrnush Parsipur’s prison memoirs. I don’t know if you’ve ever read it.

Yes, it’s an amazing book.

But what’s interesting, because though in your book, he is spending most of the time in a solitary cell, Shahrnush’s memoir is all about her interaction and imprisonment with the other women prisoners.

In your book one is left completely with Yunus’s loneliness, his psychological state as it journeys between the past and the present, the interior of the cell to the outside world. Sometimes I really felt for him, saw him as an innocent poor man, who was wrongly arrested and imprisoned, while other times I intensely disliked him and saw him as a selfish and corrupt person. But I always saw him as a tragic figure. How did you go about creating those moments? What did you draw on, having never been in prison yourself?

Well, the prison novel is a genre, you know, and there are lots of examples of that, especially in the Middle East literature. I’ve read quite a few really amazing prison novels by Egyptian writers for instance. But almost none of the books I have read is set entirely in solitary confinement, or even spends much time there.

So that was the challenge I took on. I thought this was a gap that needed to be filled. At the same time, one reason that nobody writes a novel that’s set entirely in solitary confinement is that it’s a nightmare for a novelist, because it’s just a guy or a woman sitting in a small room, no possibility of action or dialogue or anything else.

But you really kept the reader on the edge. There are very subtle things happening in the room and small details that capture the imagination of the reader. I was really hooked. But I want to ask you one much more philosophical question. In your book is there any form of optimism?

Nope. (They both laugh.)

Okay, but we’re talking at a moment during the season of coronavirus when it can feel like doomsday. When we’re all looking for a glimmer of hope, feeling that there has to be light at the end of the tunnel, no? I keep thinking about Yunus and wonder about life after imprisonment. Do you feel there could be a transformation in a person like that after those four years that to the reader would mean something? Would he have a perspective, even in a philosophical way, that could give him a constructive way of moving forward with his life? How do you see his transformation as a person now that he’s out? How would you describe that? Is it still going to be very dark?

I don’t really think about the world in terms of optimism/pessimism. It’s not part of my intellectual universe. In this novel I was just trying to figure out what happens to a person who spends a lot of time in solitary while being intensely interrogated. It’s a very complicated experience. In some hours of the day you talk to someone who has really dug deep into your life and brought out all your demons and is forcing you to stare at them. Then, when you are back in solitary, it’s extremely lonely too. That contrast was also something I had in mind.

I think my goal was twofold: first, to understand the interrogator, second, to understand what solitary confinement does to one’s mind and body. I’m not sure if I ever thought about this story in terms of optimism or pessimism. Though when he comes out the Green Movement is taking place. It’s 2009 and it’s right after the election, and there’s a lot of optimism in the air, among other things.

Exactly, which was really very fascinating. And it was so interesting that there were moments when he really wished to see his interrogator Hajj Saeed, he actually missed him. And that when he went on the trial, even though it was taking forever, he was just so happy to be sitting there among other people. So maybe the perspective is that at the darkest moments of life one takes great comfort at every glimpse of light and hope.

One big curiosity for me is whether you have plans to translate this book back into Farsi for the Iranian readers.

I can’t translate myself. I’ve tried to translate my other stuff, short stories and essays, a couple of times before, and never managed to go that far. So no, but I hope to find someone to do it in near future.

What do you think the reaction of Iranians will be to the book, as opposed to Americans or other Westerners?

I have no idea. I’ve thought about that, but I really have no clue because, as far as I know, no novel similar to this one has ever been published in Iran.

I can already tell you that it would be very mixed reaction because in my experience every time an Iranian artist living and working in diaspora succeeds, initially she or he faces some degree of suspicion and criticism by local Iranians, who wonder if the work was made exclusively for the Western audience. But luckily with time that changes.

Finally, Amir, are there issues that you feel like we have not covered, things that I haven’t managed to bring up that you would like to talk about?

I would like to acknowledge the courage and generosity of people who talked to me about their experiences in solitary confinement because this book, especially the solitary chapters, would have been almost impossible to write without those conversations. Overall I gathered testimonies from about a dozen people, which I fictionalized, but also stayed pretty close to their accounts.

I think the success of your book is that you’ve managed to write something that is so timeless and universal. And even though it goes under the skin of the Iranian society in particular, I really think that a lot of people will identify with it, though I can’t say that they will exactly enjoy it because it’s really painful stuff. We need stories such as yours. I find your book a very important one, and felt very privileged to have access to it in advance of its publication and I continue to think about it.

That’s amazing, Shirin, thank you. Hopefully when we are done with this current nightmare, we’ll meet in person.

Yes, I would love that.

-

.

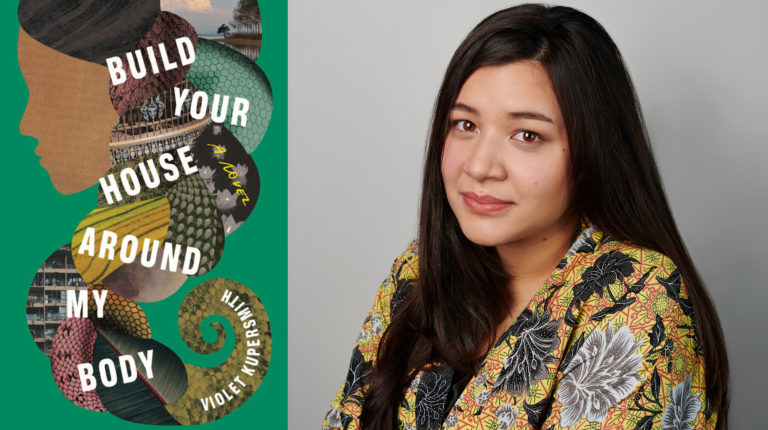

Then the Fish Swallowed Him

By Amir Ahmadi Arian

Published by HarperCollins

Yunus Turabi, a bus driver in Tehran, leads an unremarkable life. A solitary man since the unexpected deaths of his father and mother years ago, he is decidedly apolitical—even during the driver’s strike and its bloody end. But everyone has their breaking point, and Yunus has reached his.

Handcuffed and blindfolded, he is taken to the infamous Evin prison for political dissidents. Inside this stark, strangely ordered world, his fate becomes entwined with Hajj Saeed, his personal interrogator. The two develop a disturbing yet interdependent relationship, with each playing his assigned role in a high stakes psychological game of cat and mouse, where Yunus endures a mind-bending cycle of solitary confinement and interrogation. In their startlingly intimate exchanges, Yunus’s life begins to unfold—from his childhood memories growing up in a freer Iran to his heartbreaking betrayal of his only friend. As Yunus struggles to hold on to his sanity and evade Saeed’s increasingly undeniable accusations, he must eventually make an impossible choice: continue fighting or submit to the system of lies upholding Iran’s power.bGripping, startling, and masterfully told, Then the Fish Swallowed Him is a haunting story of life under despotism.