Siri Hustvedt and Carmen Boullosa were scheduled to appear together at The Center for Fiction on April 14th to celebrate the launch of Carmen’s novel, The Book of Anna, published by Coffee House Press. Instead, we asked Siri and Carmen to have the conversation they would have had in person by email. This rich and fascinating piece is the result. (In it, Carmen’s words have been translated from the Spanish by Samantha Schnee.)

In The Book of Anna, Sergei, son of Anna Karenina, meets Tolstoy in his dreams and finds reminders of his mother everywhere. Boullosa brings the voices of coachmen, sailors, maids, and seamstresses to this playful, polyphonic, and subversive revision of the Russian revolution, told through the lens of Tolstoy’s most beloved work.

We know how difficult it is for authors whose books were published in the midst of this pandemic, so we hope you will lend your support by purchasing the book here.

What was the seed, kernel (I will avoid the word germ under the global circumstances) for The Book of Anna? Such beginnings can be hard to retrieve, but the evolution from initial catalyst to full-grown text is something that interests me.

There was a new film of Anna Karenina coming out and an editor friend asked me to review it, so I got out my copy of the novel. I would never have done that without being prompted; as a young author I was decidedly in Dostoevsky’s camp, and on top of that I particularly disliked it as a teenager because my stepmother said it was her favorite book. (I now know that was a lie—she never read it; she was a thoroughly ignorant woman.) As I reread it, the thing that piqued me, that hooked me, (let’s say it infected me) was the fact that the main character had written a book—Tolstoy says so—and that the book disappeared into thin air, there was no further mention of it.

That was irresistible to me. I felt a need to return to Anna the book that I imagine (had it been published) would have provided vital oxygen to her life, joy, satisfaction, and an inoculation against the torments of Vronsky. (Her jealousy of him seems to stem from her dissatisfaction and the tiresomeness of such a mediocre fellow who was so inferior to her.) I’ve spent years reading women authors (from my own literary tradition) who are indispensable, yet no one remembers them, and if they ever do it’s only to say how “bad” they are.

And so I tried to write Anna Karenina’s book for her. My first attempt was an homage to Pushkin, written in verse. Pushkin’s forebear was Peter the Great’s African godson [1]. Tolstoy once wrote that meeting Pushkin’s daughter (who had the skin, as Tolstoy says of Anna, “the color of ancient marble”) helped him shape the novel.

[1] Abram Petrovich Gannibal, a man of African origin who was kidnapped and given to Peter the Great before being freed and adopted.

But that version was no good—apart from the fact that it gave me a year’s worth of work. I set it aside and gave up, although I did have had the courage to give it to a friend who agreed with me that it didn’t work.

Once I had dropped this pursuit of justice, I became obsessed with something else: giving Anna Karenina her two adult children. I have two adult children and it’s an experience that can’t be equaled; my mother died when she was 36 and my six siblings and I were still children. Of course, Anna and my mother have absolutely nothing in common but in my loss I made that connection. That’s why I wanted to return Anna’s children to her. And then I found myself in Russia at a significant moment that seemed much like the significant moment in Mexico, which didn’t last long but it swirled around me as I wrote.

That’s how it all began. With two quests for justice that were acts of imagination.

This is just what I had hoped for—the story behind the writing of the story. In college I was immersed in Russian intellectual history and worked on Tolstoy. I read A.K. closely and have read it twice since, and I do not remember mention of a book! Embarrassing. I remembered that Pushkin’s oldest daughter Maria Alexandrovna served as an inspiration for the character of Anna, however. You originally planned for her to write her own Eugene Onegin? The book she does end up writing is a complex fairytale. It is a form in which human desire (wish) triumphs over the stupid machinery of blind fate. And because Anna is the fairytale heroine, Cinderella and others, she gets her children back and her just reward. The book does seem to be also about reparation, about repairing, mending the past—a fictional past (the novel A.K.) that merges with the historical past—1905 in Russia—real historical characters mingle with fictional characters in your novel and comment on their status as such. Could you discuss your thoughts on the role of the “imaginary” and the ”real” inside the book?

I realize that, now that you mention it, my first instinct was passive when I decided to try to write Anna Karenina’s book. I approached it as a sort of duty (and I think that was my fundamental mistake, because writing a novel isn’t a duty, it’s something more than a duty and all that comes with it—the honor or the glory. Writing is more like breathing, it’s less voluntary, more organic, more essential, of course it’s a duty as well…. But I digress.) To write that first version (which I believed was my duty to A.K., and we can all agree that there are no duties more compelling than those we owe the dead—and that’s not just burial, remembrance, and honoring their memory. At that time, A.K. was recently deceased for me, a real person who had just died; when I finished rereading Tolstoy’s novel she was the person who had most recently left me bereaved, and in that instant of my fascination with her—thanks to the magic created by a great realist novel—she was the dead person I owed something to….) But I’m digressing again. I was saying that when I decided to write that first version I followed all the directions Tolstoy gave me to the letter: a book for children, with an “educational” aspect, that would have appealed to both A.K.’s brother, Oblonsky, and an editor-writer. At the time I believed that A.K.’s book needed the kind of logic you find in the popular tales that appealed to musicians and other artists of that era. But I also believed that it had to tell the story of something A.K. carried in her veins…

In that first version, though I wanted to give A.K. a story that was truly fiction, I knew it also had to be something in her bones, A.K.’s bones… and I decided that it should be the story of Peter the Great’s godson, which was literally in her bones, in her fictional genetic code, her very self, her origins, he was “written” in her bones.

Because when I was rereading I noticed that in some of A.K.’s behavior and characteristics, as portrayed by Tolstoy—her lithe body dismounting her horse, a way of being different from others, the color of her skin, her dark, very dark curly hair—he was manifesting the memory of her African ancestor in her physical being; in order for her to be born (as a fictional character) he had stolen from real life (in the form of Pushkin’s oldest daughter, Maria Alexandrovna). . . So I decided that the story would be about Peter the Great’s African godson, but not a historically correct one; rather, it would be a fairy tale. He wouldn’t arrive in Russia as a child slave, a gift to the Tsar; instead he would arrive in a hot-air balloon, a la Verne. I was stringing things together, out of duty; some worked and some didn’t, and A.K. was almost an afterthought, like a varnish on the text because in museums the bones of the dead look like they’ve been varnished. And since the story was about him, why not make it an homage to Pushkin? A totally different narrative style, using verse, because, like him, A.K. would also be telling a story for everyman, one that could be sung like the epic poems popular poets used to recite.

Everything was wrong from the outset in that first version.

But there was something that stayed with me when I set that version aside, and I finally wrote the novel that had been forming slowly—authentically, not out of a sense of duty, but rather in the mode of what is essential, organic, fundamental, necessary, both mine, and, as often happens in writing novels: the novel´s not mine, the book is an entity in its own right. I’ve always had the impression that when I write a novel I’ve had the good fortune to discover, like an archaeologist or an explorer, I ought to be able to figure out how not to ruin or break it, and not damage it with my tools, my pen. . . .

The thing that stayed with me from that first version was the fact that History and Fiction share the same space, they’re never separate; rather, they’re the same thread in the same plot. At least that’s what the novel that I was forming—or discovering—demanded of me, not only because A.K.’s grown children had to live in History—historical characters and moments eventually become part of the world of Fiction—but also because A.K.’s book needed to be like stories that had popular origins, which captured the fascination of the populace, but would mirror the turbulence of the times, her unquenched desire, her diamond-like love-passion (as Sor Juana would call it):

Al que trato de amor, hallo diamante,

y soy diamante al que de amor me trata,

triunfante quiero ver al que me mata

y mato al que me quiere ver triunfante.

Si a éste pago, padece mi deseo;

si ruego a aquél, mi pundonor enojo;

de entrambos modos infeliz me veo.

The one I love becomes a diamond

and I’m a diamond to him who loves me,

I want to see the one who kills me triumph

and kill the one who wants to see me triumph.

If I pay this one, my desire wanes;

if I beg the other, my honor’s inflamed;

betwixt these two, unhappy I stand.

(Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, Obras completas, Volumen 1, Fondo de Cultura Económica. México, 2012.)

A.K. is unhappy, she is under the spell of her own fantasy, a novella–the story she has written. It’s no longer the version that Oblonsky read, the one that might have brought her honor and glory, but it represents her unhappiness authentically.

A.K. reacts as if she were a character in her own dream: she dives into her love story (the one she herself imagined, becoming a character in the novella she´s writing) without realizing that the kind of love she feels for Vronsky is a diamond, and there’s no room for her in it, unless she is embalmed, immortalized like an insect in amber . . .

I’m not sure whether I’ve answered your question, Siri, or whether I’m responding to something it awoke within me, headed in a different direction.

Carmen, to my mind, all directions are open, and I am struck by three essential points you make. First, the book left you bereaved. That is how I felt each time I finished it. Losing Anna is terrible for the engaged reader, a truth which underscores the emotional power fiction and fictional characters have over us. As Freud noted about dreams, although the events in them are not real, the feelings are. Dreaming and reading novels are lived experiences. We wake from dreams and close books to find ourselves back in everyday reality, but they both can leave us jolted. Second, that jolt was a catalyst for you to act, to repay a debt you owed the character: her book. Now, if I have understood correctly, that sense of duty created your third point: a misstep. It is a misstep I have dubbed “the outside in not the inside out.” In other words, the writer imposes a structure or meaning on the text rather than allowing the book to unfold as an organism. I was delighted to see the word “organic” in your answer, along with the trio, “essential, necessary, fundamental.” Writing is an embodied, rhythmic activity that requires openness to unconscious prompts that are not predetermined or schematic. I have abandoned a number of manuscripts that were written from the outside in. They died on me.

So, I think we agree, fictions can and do carry profound emotional truths. The realist novel is situated in real histories and actual events. Fictional characters often mingle with real people on their pages, as they do in your book and that mingling is part of human thought, mental activity itself. You make strong connections in the novel between waking and dreaming life. Your characters dream and Anna’s characters in her book dream, and the dreams have meanings for them and for the novel as a whole. I have often thought of novel writing as a form of dreaming while awake. The dreams you present often have potent sexual (as well as social) meanings. I love the erotic leather key that makes its way between the legs of our fairytale heroine. Could you elaborate on both the role of dreams in the book and their sexual significance? I am thinking specifically of women, repression, sexual awakening, and the sly way you incorporate female masturbatory pleasure into the novel.

Dreams carry our fingerprints, they’re the histories and worlds that develop without the necessity of actors other than ourselves. There’s a thread of what is and what happens in the world that runs through them (so personal, unique, impossible to describe in words, filled with our memories, our anxieties, and Myth—the house ghost that opens and closes the doors and windows of how we behave and act—which pretends to be universal and has the glamour of the eternal). And the external world leaves its marks on our dreams, too. The I, the Myth, the World.

I think that in the pages I wrote as A.K., which are just part of The Book of Anna, Dreams, or the Land of Dreams, are in control. And at the center of that Dream is the clitoris.

Let me try to break it down further: the pages I wrote as A.K. aren’t ruled or governed by wakefulness, just the opposite. They’re not “natural” dreams, they’re suffused with laudanum. Not laudanum (or opium) from the world of wakefulness, but rather from the realm of dreams. And at the center [of that story] which has no other characters, there’s the clitoris, the sexual awakening of that girl, who’s alone, trapped, coming to age in a frigid castle, and her body begins to awaken (with the turn of the key) to solitary sexual pleasure. The prince doesn’t show up—that would be a mistake: A.K. herself had tried that with her “blue prince”, Vronsky, who turns into a tin soldier over the course of the novel.

I completely agree with you when you refer to writing a novel as “a form of dreaming while awake.” In my pages I take your description literally and leave the story in the hands of Dreams, as if I had heard you say that to guide me. It’s a real novel, and the rest of the book is a “touching base” exercise. The strange thing is that in the “exterior” (or crust) of the novel The Book of Anna, there are some dreams, but they are dreams “governed” by the author. Tolstoy himself interrupts them—it’s a device, a dream governed by the liminal place between wakefulness and sleep that is the essence of writing a novel.

On the other hand, this erotic awakening isn’t directed by my wakefulness. There’s no Father Gapon, no Bloody Sunday, no gatherings of the proletariat. It’s free. Its slogans could be: Sexuality will free you! Free sex will never be conquered! The clitoris will escape oppression of the monarchy and the unjust social order!

But to get back to what I was saying: the world leaves its mark on dreams. I say that because, when I reread what you’ve written to me (as well as your essays and novels, but let’s leave that for another day when I’ll put my name on your dance card and invite you onto the floor, and I’ll take the lead—as a man might say—and take you dancing to your own beat) it occurred to me that the rational becomes as personal as the ungovernable Land of Dreams. And I think—now I’m getting tangled up in the question—about how broad the Land of Woman is. Broad, extensive, diverse, marked by a plethora of ways of being, personalities, people. Planet Woman has every kind of geology. Then, in another place altogether, there’s the clitoris. The clitoris makes each of us female humans into sisters. It’s the finest jewel in all humanity. The one most honed by culture. It encompasses words and silence—like poetry—the physical and the intuitive, fantasy and flesh, and more than anything else in all humanity, the Human Spirit. The clitoris, the soul, the not-irrational, far surpassing words.

The clitoris has become an intellectual obsession of mine. In my first novel, Antes (which Octavio Paz published when I was still very young, and which was translated into English by Peter Bush as Before—though it spent nearly two decades “in the drawer”), when the girl’s body becomes a woman’s, she dies. At first it seems that she dies before discovering her clitoris, from the fright of becoming aware of her body and a life with a clitoris. Or, if her clitoris is fully awakened to adulthood (because she’s telling the story once she has died, in the voice of a woman), the voice of her clitoris.

This is the topic of my first book and also my last—the one that’s about to appear in Spanish—a novel in which I speak literally about the birth of the clitoris in History. The Book of Eve is narrated by Eve, who tells us how it really was. It has nothing whatsoever to do with penis envy; it’s clitoris envy and the power of creation, and so forth that cause the “oppression” of women.

It’s not “In Search of Lost Time”; it’s “In Search of the Frightening Clitoris”. And in A.K.’s pages she conquers her own clitoris in the context of a fairy tale, in a mode of popular storytelling that I suffuse with laudanum to be able to give A.K., if not her own voice, the voice of her clitoris.

That sounds quite coarse. But in A.K.’s pages we see and feel that awakening. This place where consciousness is born particularly fascinates me.

I feel that I have just read a small work called “Hymn to the Clitoris.” In my novel The Summer Without Men, I make comic sport of two Columbuses, the one who purportedly “discovered” the “New World” (1492) and Renaldus, the physician who claimed to “discover” the clitoris (dulcedo amoris) in 1559. The arrogance of both claims is, of course, stupefying and ripe for ridicule. You stress the diversity and difference of womankind at the crust—history, politics, class, color—as opposed to an erotic embodiment that is shared by all those born female. Erotic awakening is a form of genuine discovery by the girl at a moment of her coming of age and to consciousness. The prince who awakens the princess, the European explorer who conquers virgin lands, the doctor who names female anatomy are NOT KEY to this story. For me, The Book of Anna is a feminist novel. I would like to know more about the connection you make between the freedom of embodied feminine knowledge and consciousness of “the crust”?

“Crust” vs. Clitoris. It’s a subtle distinction and (as always) such categories are ill-fitting. They’re fine for starting conversation and initiating comprehension. The “exterior” (the crust) and, on the other side, clitoris territory (to give it a name).

You can think of “crust” novels and “clitoris” novels and then there are novels that have a bit of both. And the ones that squarely blame the clitoris (just look at Helen of Troy) pursue their adventures in strictly masculine guise. Most stories employ both.

It makes me think of a volcano; its clitoris (its mouth and innards) and its crust (its body and exterior).

It reminds me of Flora Tristán, the hyperfeminist, social-justice warrior, who was astute and wise enough to utilize the clitoris to gain ground in the “exterior” with the purpose of changing the social order of the “exterior.” She even realized that the “exterior” couldn’t be changed and wouldn’t achieve justice, if the struggle for women’s rights wasn’t at the forefront of the transformation.

In her case (in her life) the two territories aren’t separate: in her memoirs she tells the story of walking past the Sorbonne with her husband (whom she no longer wanted to be married to, she had already left him, but she was unavoidably tied to him by Napoleonic Law), who hit her. She was saved by some law students. Flora’s husband demanded that the students leave them alone–“She’s MY wife!”—so the students left; she is HIS wife, which means he can do whatever he likes with her, including beating her to a pulp.

In her life crust and clitoris are woven together; of course, we remember and admire her for her crust, but without her clitoris her crust would have crumbled. The same would have been true for her clitoris without her crust—it would have fallen to pieces.

But let’s get back to The Book of Anna: the crust is located specifically in the pages I (as an author) attribute to her, but the clitoris permeates the pages written by Anna. The plot isn’t dictated by the needs of a social or logical, visible “crust,” but by the fluttering of a clitoris. However, it’s propelled by legs made of a kind of crust, it doesn’t get stuck clitoris-ing.

Siri, do you think that all plots require a modicum of crust?

I’m looking at the webcam of the Popocatepetl volcano. I used to live in an apartment, here in Mexico City, where I could watch the volcano from one of the windows—these days I have to make do with webcams—awestruck by its belchings. It’s fascinating, the clouds of smoke dance, becoming thinner or denser, each one is different; if it’s night, suddenly you see the sparks of light flying up from its bowels, out of its mouth. The most interesting thing about the volcano, for me, is its clitoral qualities. Yet, what would I be able to witness without that “crust” that puts everything in context? They both need each other, the body, the crust of the volcano whose shape is altered by the insatiable clitoris within, which is necessary for me to be able to appreciate what really interests me.

What do you think? What would you think of a novel that didn’t have any crust at all?

I’m thinking of the wonderful erotic poems (so clitoral!) of Delmira Agustini. But there are fragments of crust in them, too, almost melted by the lava pouring out onto us… (How to do that in an novel…?)

I’m undoubtedly fascinated by narrative “crust” as much as I’m fascinated by the body of the volcano I try to ignore but can’t, because it’s the connection to what I love. That useful, mechanical part that keeps things moving, going places—and this is where the image of an active volcano doesn’t work—is important to me, too. Crust, that’s not rigid, but infused with clitoris.

Carmen, I am a little worried we may drown in this metaphor. I am now envisioning various kinds of bread and their various crusts, not to speak of volcanoes with crusts of another kind altogether and erupting lava. I think we both accept that unconscious forces are at work in making books and that energy is also, in an expansive sense, erotic. But you also seem to be making a distinction between rational and irrational or superstructure and substructure and the fact that neither of these is wholly distinct from the other. The reason over passion or mind over body dichotomy and the association of man with mind and woman with body, which has been with us since the Greeks, has led to the denigration of all work done and made by women.

Every literary text runs on its own internal logic, finds its own form, as Gertrude Stein once observed. It should not be forced, but it must have rigor and structure. The book’s logic requires communication with the reader, a shared language. If a text pushes too far beyond what can be shared, it risks becoming word salad (the psychiatric term for some psychotic patients’ speech and writing). Word salad can be interesting, and it can generate meaning, especially in poetry. There are any number of poets that dance at the edge of meaning (Emily Dickinson and Paul Celan are two great examples), but a novel with no crust would risk becoming all lava.

Another theme. The portrait of Anna plays an important role in the novel, the representation of a character in a novel who is herself a representation—words on the page that become words on your page. At the end of the book it is exploded by an anarchist bomb. Can you discuss the meanings, i.e. internal logic, of that destruction?

In Anna Karenina the first person who tries to paint a portrait of Anna is Vronsky (in love). It’s a disaster, he can’t finish it, he’s an amateur. The second person, Mikhailov (the great painter), does it because he needs the money, and according to Tolstoy it’s a masterpiece. I love this second portrait—the fact that the painting´s born out of financial need doesn’t bother me one bit, it doesn’t diminish my admiration in the least.

My novel recovers two of A.K.´s belongings: the dress she wears in the box at the theatre–when she wears it we see her in all her splendor; and the painting, her portrait, in which she’s radiant. Both of these play a vital role in The Book of Anna. Mikhailov’s prestige as an artist (favored by his son’s relation to the Tsar) lends the portrait a kind of glory, whereas her dress has received the worst of treatment. In these two objects A.K. covers the spectrum of society, she moves from apex to nadir in a way she could not have done in real life. And with these two objects she embraces the city.

Her dress characterizes lovely Clementine, the vengeful anarchist leader of the seamstresses, who has repaired it to wear it. On the other hand A.K.’s portrait is desired by the Palace.

Both objects are protagonists with their own lives; they both follow their own roads that must lead to destruction. They belonged to the old A.K., not the one who wrote the pages I attribute to her; rather, they represent the classic A.K., the one we all know, the one unable to bond with her infant daughter, the one who, despite her intelligence, couldn’t figure out how to overcome her social disadvantages. Once I had given A.K. the pages I made her write, they were destined for destruction, because that was their role in her city: to share, with her dress and her portrait, a triumphant death that, though it wasn’t pre-meditated, was true to their nature.

When I “murder” her portrait I don’t kill A.K., I don’t make her drink another draught of death. I’ve given her own pages to her. Those other objects belong to her former destiny, one in which there had been no room for the beautiful, unique A.K. When I murder her portrait I’m repairing her fall to the train tracks, symbolically. She doesn’t die possessed by jealousy. She dies travelling through her city, surrounded by her people, in a Revolution. When A.K. falls to the tracks, she is alone and absurd. In Tolstoy’s description her suicide appears to be stupid and careless, it’s not considered, it’s a misstep she takes out of blind jealousy.

The death of the dress and the portrait (and, alas, the manuscript reproduced in The Book of Anna) returns to A.K. her life with others. And isn’t that what life’s about?

Now, I fear this interpretation of mine is seeded in my childhood, and the fact that today, as I write these lines, it’s Easter Sunday. When I was a girl I was told this was the most important day in the year, because it was when the one who had died a few days earlier came back to life. He came back to life, only to move on into the kingdom of the dead. I fear that it seems I’m reading the end of my novel through this lens. But it doesn’t have the scent of the roast lamb we ate at those large Easter celebrations my parents used to take us to when they belonged to the Movimiento Familiar Cristiano.

What happens in my novel is nothing of the sort. Neither the portrait nor the dress sacrifice themselves. They’re playing their roles in a work of fiction. The novel needed to end, it needed to disappear whatever had brought it into being, so that the ritual we call reading could be completed. Its narrative logic dictated that the dress that had opened the novel also had to depart the novel, and the portrait along with it, into the land of eternal fiction.

In closing, I wanted to make the novel immune. The others who join these two objects in their fate (I won’t specify who, because there are already too many spoilers in this answer) are “collateral victims.” That is, if you can have collateral anything in a novel, and I don’t think you can.

And Carmen, to that bid for immunity, I can only say, Amen.

Brooklyn-Coyoacán, April 2020.

-

.

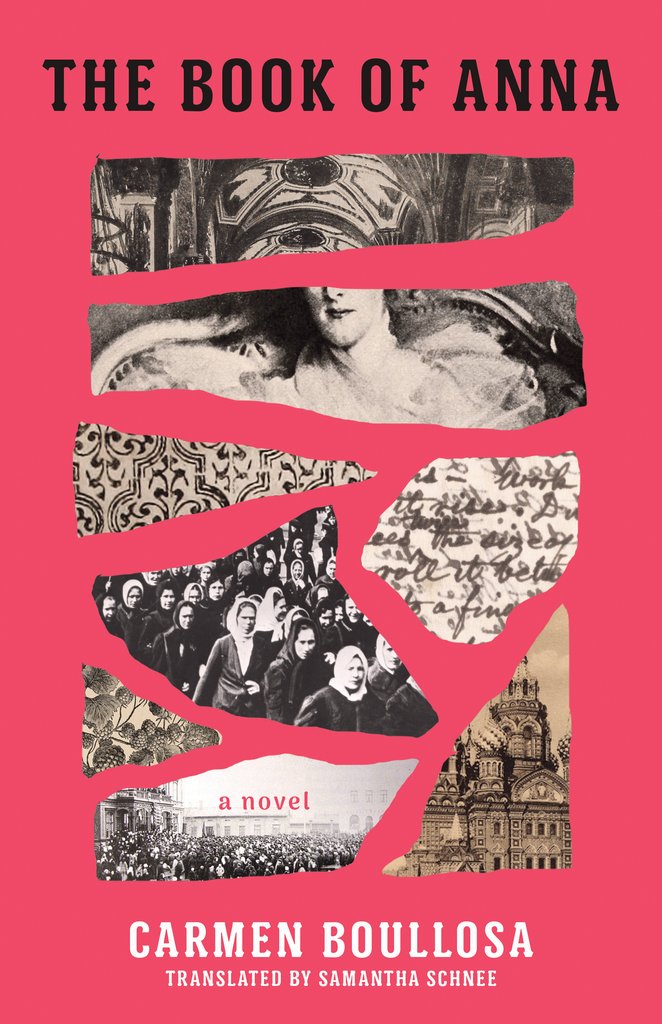

The Book of Anna

By Carmen Boullosa

Published by Coffee House Press

Saint Petersburg, 1905. Behind the gates of the Karenin Palace, Sergei, son of Anna Karenina, meets Tolstoy in his dreams and finds reminders of his mother everywhere: the vivid portrait that the tsar intends to acquire and the opium-infused manuscripts Anna wrote just before her death, which open a trapdoor to a wild feminist fairy tale. Across the city, Clementine, an anarchist seamstress, and Father Gapon, the charismatic leader of the proletariat, plan protests that embroil the downstairs members of the Karenin household in their plots and tip the country ever closer to revolution. Boullosa tells a polyphonic and subversive tale of the Russian revolution through the lens of Tolstoy’s most beloved work.

“The latest novel from one of Mexico’s finest experimental writers is a madcap metafictive romp that picks up a few decades after Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina leaves off. But it’s also an absurdist tour de force account of early revolutionary activity. . . . Reminiscent of Bolaño, Borges, and Pynchon, but Boullosa’s utterly original voice is at its best when it’s let loose.”—Kirkus