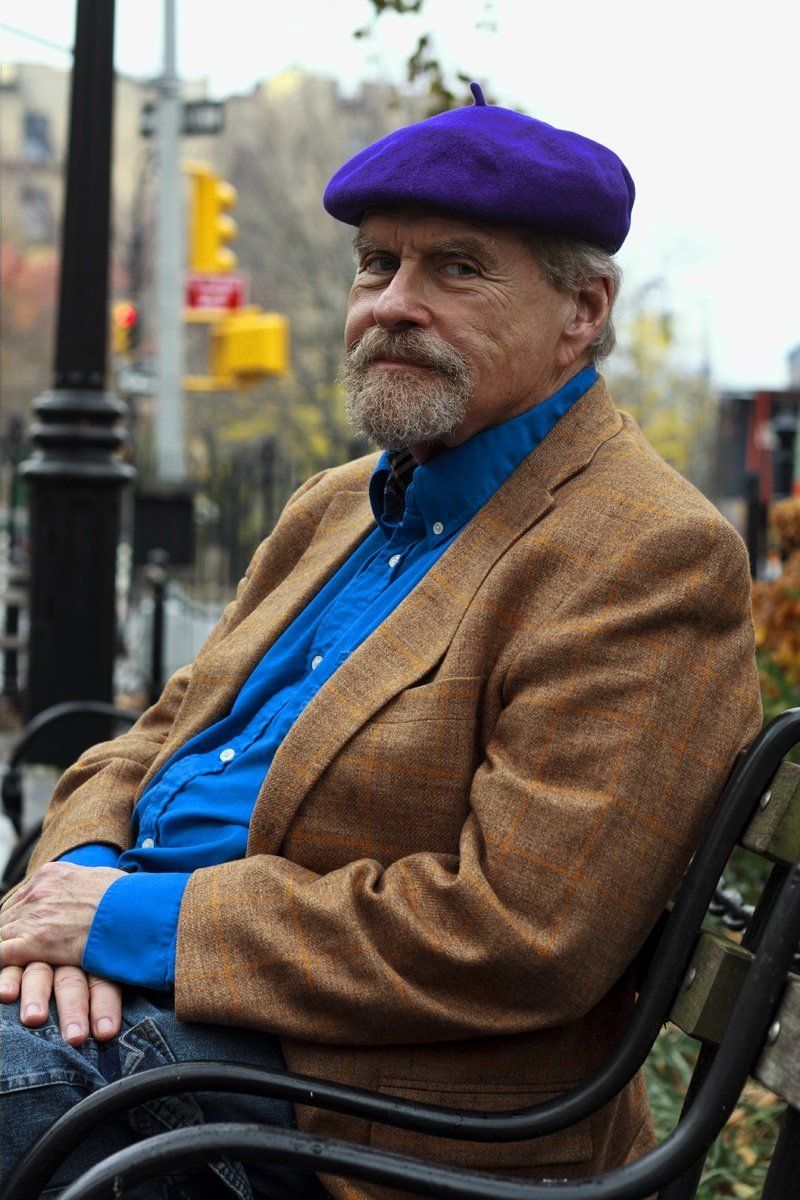

Lawrence Block is surely one of the best-known, most successful, and beloved crime writers in the world. Ask any crime writer, (as I was recently) to choose their top 5 crime novels of all time and inevitably a Larry Bock novel is on that list (as it was on mine). He has written several long-running series with protagonists like Matthew Scudder and Keller, so well-known the characters have become part of crime fiction lore. As the author of more than 50 novels, 100 short stories, books on writing, and more, he has received every crime writing award, including the Edgar, the Shamus, the Nero, the Anthony, the Cartier Diamond Dagger Award, many of them won multiple times. His most recent novel is Dead Girl Blues.

Jonathan Santlofer: I’d like to start by asking you how your writing career began. I know a little about your early work, the pseudonymously published soft-core porn novels and the crime adventure magazine writing. Can you tell us why and how that came about and what you think it gave you as a writer?

Lawrence Block: I was fifteen, a high school junior, when I knew I wanted to be a writer of fiction. The idea had never occurred to me before, and from the instant it did I never seriously considered anything else. Four years later I was selling stories to the crime fiction magazines, so it didn’t take long. Which was probably just as well; I’d like to think I would have persisted in the face of adversity, but I’m not sure that’s the case. I hear now and then of someone who writes eight or ten or a dozen novels before finally selling one, and I shake my head in amazement.

Early on, all I really knew was that I wanted to be a writer. I wrote poems and short stories, and I sent out everything I wrote, and I got a lot of rejection slips. Then after two years in college I sold a story to Manhunt, and then I got a summer job at a literary agency, and I dropped out of school to keep it. I stayed there for the better part of a year, reading slush-pile crap and writing encouraging letters, and learning something every day. I continued selling crime stories, and anything else that came along.

A year there was enough. I wanted to be a writer, not an agent. And I didn’t want to be drafted, so I went back to school and went on writing. My first book was a sensitive novel of the lesbian experience, and it sold to Fawcett, the first publisher who saw it. I called it Shadows. They changed that to Strange Are the Ways of Love, and called me Lesley Evans. The book’s back in print after all these years, and now it’s Shadows once more, and now I’m Jill Emerson.

Back at college, I went on writing crime stories, and through my former employer got into the emerging world of paperback erotica. By the end of the academic year I’d sold four or five novels and a batch of stories, and got a letter from the college saying they thought I might be happier elsewhere. True dat.

One of things I find most admirable about you is that you are always growing, creating new character series (characters who are totally different from each other), experimenting in short stories, unlike some crime writers who create a successful character and stay with him or her for life. Can you discuss this need to change, to take chances, to often push the boundaries and limits of the genre?

I’d love to think of it as a virtue, but I’m not sure I can. The problem is I’m easily bored. If I don’t like what I’m writing, I tend to abandon it.

And I don’t think for a moment that it’s a great move from a commercial standpoint. The writers who do best in the marketplace are those who tend to do the same one thing over and over until dementia gives them permission to stop. By writing different kinds of books, I’m sure I’ve cost myself money.

In the short run, anyway. On the other hand, I’m still in the game, and I published a new novel 60+ years after the first one, and some readers have said they think it’s my best book. Admittedly, there are plenty of others who think it’s crap, but my point is that if I wrote the same thing over and over, or made an effort to give readers what I figured they wanted, I’d have quit doing this ages ago.

You’ve written several books on the craft of writing (I can think of at least four). Can you tell us why you wrote them, and how the books differ?

Writing about writing came early to me; when I was reading slush at Scott Meredith I wrote a couple of thousand words on dialogue that ran in Author & Journalist. In 1976 I sold an article to Writers Digest and talked the editor into a column on fiction, and it ran monthly for fourteen years. Four of my books for writers consist of collections of those columns: Telling Lies for Fun & Profit, Spider Spin Me a Web, The Liar’s Bible, and The Liar’s Companion. The first one, Telling Lies, is consistently the sales leader, but that’s because it’s got a terrific title. I don’t know that it’s any better or worse than any of its fellows.

Writers Digest had a book division, and when I’d been writing the column for a year I was invited to write a book on writing novels. They called it Writing the Novel from Plot to Print, and it stayed in print for ages; I eventually got the rights back and updated and expanded it substantially, changing the title to Writing the Novel from Plot to Print to Pixel.

Finally, Write For Your Life is a book that grew out of an experiential seminar I developed in the 1980s. It’s could as aptly have been called The Inner Game of Writing.

Are the books for writers useful? I suspect I’m the wrong person to ask.

Lately you’ve created and edited a series of terrific and varied short story collections, more than one with art themes. Why art as a jumping off point? And are there more anthologies to come?

I’ve done a batch of anthologies over the years, early on working in tandem with that wonderful gentleman, Marty Greenberg. Marty and his staff did all the heavy lifting, and I didn’t have to do much more than come up with a theme, recruit the writers, and contribute an introduction so that readers would have something to skip. Then I played the same role with two Manhattan books for Akashic’s Noir series.

A couple of years ago I got the idea for a collection of stories, each inspired by an Edward Hopper painting. The idea just came full-blown, like Athena from the head of Zeus, and it was too engaging to be denied—though the last thing I felt like doing was putting an anthology together. But almost every writer I invited was enthusiastic, and my agent found in Claiborne Hancock at Pegasus a publisher who was equally enthusiastic, and In Sunlight or in Shadow was the happy result. It led to two more art-based collections, Alive in Shape and Color and From Sea to Stormy Sea.

More recently, I thought up and put together The Darkling Halls of Ivy, with stories set in the academic world. And there’s another in the works, with the working title of Collectibles. And that, I hope and trust, will be my final anthology. They’re a temptation for a writer who’s a little bit past it, because there’s the illusion that you don’t really have to do anything, that your name and brilliant idea will carry the day. But it’s all way more work than it ought to be, and there’s no money in it, and enough is enough.

Your most recent novel, Dead Girl Blues, is a controversial one. The opening, a violent and shocking crime against a woman, is enough to make many readers put the book down. I’m glad I did not because the rest of the book becomes a sort of analysis of the crime and the character who committed it. I think this is a dangerous and incredibly brave book to have written and published now as it appears so un-PC, though in reality ends up being an examination of violence. Can you tell us about the genesis of this book, why you wrote it, and how you feel about writing a book which contains such explicit violence?

The book came as a surprise to me. I don’t mean that I woke up one morning and there it was, written by elves. But I didn’t expect to write another novel. I did think I might write a short story, perhaps a longish short story, perhaps a novelette or novella. And I sat down at the computer and started writing, and the next day I did a little more, and so on. I didn’t really know where it was going, and when I was around ten thousand words in I found myself souring on the project. I stopped working on it, and I thought maybe I’d get back to it someday, and then I thought maybe not.

I stayed away from it for a few months. Then one day I decided to read it through, to see whether I wanted to do anything with it, and I liked what I read. I figured maybe it would turn into something. And I sat down to work each morning, but only for an hour or so, and it kept getting longer. And damned if it didn’t turn into a novel. A short novel, but it runs to 52,000 words, and that’s longer than any of the first three Matthew Scudder books. And God knows it fits Randall Jarrell’s definition of a novel: an extended prose narrative that’s got something wrong with it.

I’m very pleased with Dead Girl Blues. Some people love it, some people hate it, and—just to keep things in perspective—as with everything I’ve ever written, most people don’t have any idea that either it or its author exists. As for the violence and the darkness, hell, I don’t know. Some people think it’s too violent, while not a few find it not violent enough.

The wonderful thing is I don’t care. I don’t have to care. I never expected to write this book, so it doesn’t owe me a thing. I’m eighty-two years old, I’ve been writing and publishing books for most of those years, and this new one suits me down to the ground.

Featured Book

-

.

Dead Girl Blues

By Lawrence Block

Published by LB Productions

From the Publisher:

You might as well know this going in: Lawrence Block’s new novel is not for everyone. It’s recounted in journal form by its protagonist, and begins when he walks into a roadhouse outside of Bakersfield, California, and walks out with a woman.And rapes and murders her.

But, um, not in that order.

Right. But it’s what he does with the rest of his life that’s really interesting…

Lawrence Block has been writing and publishing crime fiction for sixty years. He’s received recognition for lifetime achievement in the US and the UK. His books have won awards and occasionally show up on bestseller lists. Several of them have been filmed.