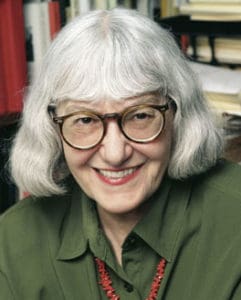

The celebrated author gave this interview--in which she talks about Holocaust writing, literary influence, and the great American novel--to noted journalist Alessandra Farkas. It was published in Corriere della Sera, Italy’s oldest and most widely read daily newspaper. We are delighted to make it available here.

Will the theme of the Holocaust always somehow be present in your writings?

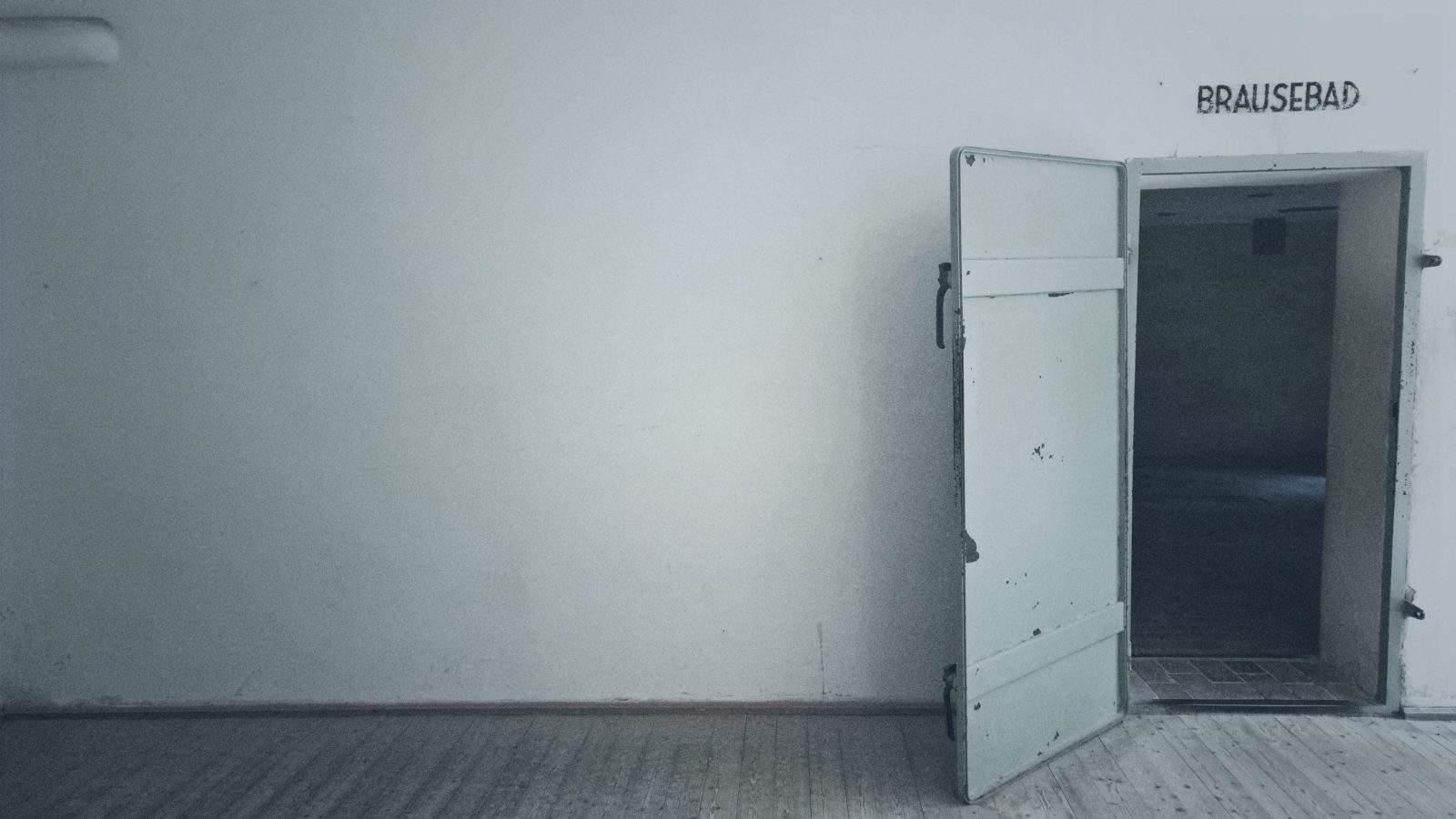

So it seems, even against my will. Though surely not in everything I’ve written; for instance, not long ago I found pleasure and relief in a comic novella, calledDictation, about the mischievous collusion of two amanuenses, one secretary to Henry James, the other to Joseph Conrad. But very soon afterward, as I resumed work on Foreign Bodies, my latest novel, I was taken by surprise — once again a survivor turned up, this time of Transnistria (and actually influenced the title). I neither wanted her nor expected her, and there she suddenly was. In principle (a principle I have violated) I am not in favor of the fictionalization or mythopoeticization of the Holocaust; the documents speak graphically and bitterly enough.

Yet it will never be possible — it has never been possible — to escape the effect of this mammoth atrocity of the Twentieth Century, which has changed the world forever. Changed the world forever, you may ask, when time obliterates nearly everything? And new atrocities mount? But sometimes time doesn’t obliterate; sometimes it deforms, and in deforming history, it teaches replication. Indeed, it inspires replication. “Never again,” that noble slogan, has been hideously transmogrified into “Of course again! Since it was done before, and so easily done without meaningful opposition, what’s to stop us from doing it again?” A lesson not lost on Adolf Hitler: “Who, after all,” he notoriously said (and we are not often enough reminded that he said it), “speaks today of the annihilation of the Armenians?” Hence Rwanda; hence Darfur; hence Ahmadinejad, his proxies, his jihadist clones, his sympathizers and cynical abettors.

And there is more. The Holocaust has produced crocodile tears everywhere, no more so than in Europe, the staging ground for the mass abduction and mass murder of Jews. The Holocaust has become a fig leaf for Europe’s resurgent anti-Semitism under its new mask, anti-Zionism (just as, historically, the term anti-Semitism, with its linguistic overtones, was a new mask for open Jew-hatred). Think of all those solemn memorials for dead Jews on a Sunday afternoon, while on Monday morning the same pious speechmakers devise brutish assaults on living Jews in a mercilessly besieged Israel. At such times there is little to choose between the speechifiers and the deniers. Which is why the Holocaust, used and abused by the criers of crocodile tears, is today more in my mind than ever. Lili, the survivor character in Foreign Bodies, has a name for Europe: She calls it Nineveh. Any reader of the Biblical story of Jonah will know her meaning.

According to one critic, Collected Stories is the book which most encompasses your literary prowess. Is this book still dear to your heart? Do you still feel a connection to it?

A few years ago, at a celebration of the twentieth anniversary of the founding of the Rea Award for the Short Story, John Updike remarked that he had arrived as a writer at a more fortunate time: when the short story was still a significant factor in the culture. A young writer beginning today, he said, would not be able to make a living through short stories, as he had. But the subject — and the issues it raises — goes far beyond the unlikelihood of selling to fewer and fewer magazines willing to publish stories. Most journals nowadays seek out the topical and the immediate — hence the ephemeral. The idea of a widely read magazine defined by its devotion to belles-lettres is as laughable as it is obsolete; what’s wanted is the news.

Like Updike’s (though never so successfully, it goes without saying), my early stories were written in that same period of the ascendancy of the short story. The major magazines all published stories; today, only two do. (My memory goes farther back, to childhood, when even newspapers featured what were called “short shorts,” one-page narratives.) Gradually, and in some cases abruptly, the venues for stories vanished, and though the (mostly academic) writing workshops continued to turn them out, the readership for stories was drying up. Or, to say it more radically, literary reading itself was drying up. Gossip, topicality, celebrity, sensationalism took its place in the magazines. And the stories that were being written tended away from ambition toward smallness, toward what were being called “epiphanies,” a large term for tiny quotidian recognitions. Who can imagine any American story equivalent to the reach and depth of Tolstoy’s “The Death of Ivan Ilyich,” or Chekhov’s “Ward Six,” or Chaim Grade’s “My Quarrel with Hersh Rasseyner” or Lampedusa’s “Ligeia”? All of these, for Americans, must be read in translation. And all are expansive: long stories; some would categorize them as novellas. But the workshops typically eschewed the deeper imagination, and were dedicated to replications of Raymond Carver: i.e., stories short, dry, and small.

Of my Collected Stories, I can only say that my heart was after the long and the large, and sometimes even the metaphysical. My favorite of all of them was written long ago, after I had first come upon Lampedusa’s “Ligeia,” which I stumbled on under the awkward title “The Professor and the Mermaid.” I had never read anything so mysteriously enthralling. It inspired me to paraphrase it in some way, to transform it through another lens, and from this came what I still regard as the most successful story in the collection: “The Pagan Rabbi.” I recall how, writing in the middle of the night (a lifelong habit), I puzzled over how to depict the nature of a dryad’s speech. A dryad is a tree spirit; a tree is botanical, like odorous weeds and flowers; and suddenly it came to me that the dryad’s “voice” must be in the form of a fragrance to be apperceived by the olfactory nerve. Such joy when I hit on that!

What criteria did you use in selecting the 19 short stories? What in your mind ties together the heterogeneous subject matter and characters?

Criteria? Only that they were there. As for the relation between subject matter and character: an idea produces a situation, and a situation produces a character. Some writers may begin with a character, which then leads to a situation; but for me it is usually a wider notion that narrows into a conflicted condition. For instance, I have been mulling a story about two elderly poets, childhood friends, whose minds have acutely diverged, yet are compelled to meet after a lifetime of estrangement. One has achieved some celebrity as a modernist; the other is in eclipse, charged with archaism. What will happen at this crucial meeting (in the presence of a much younger person) I won’t know until I begin to find out through the act of writing. Will it be a comedy? Possibly, though tinged with sadness. I suspect, though, that so-called “archaism” will win. (And will I ever actually write this story?)

How did the idea to retell the story of Henry James’s The Ambassadors in your new book Foreign Bodies come about? And what was your real goal in reversing the meaning of the classic?

What I had in mind was James’s celebrated “international theme,” the contrast between Europe and America that he repeatedly drew in his novels and stories. For James, Europe was sophisticated high civilization, a time-honored and unparalleled heritage of art and beauty and knowledge, while America stood for the raw, the naïve, the gauche, the untried, the unschooled, the foolishly innocent. But after the bloody darkness of the Second World War, it seemed to me, and particularly in the wake of the stench of the Holocaust, this contrast no longer held: Europe’s heritage of art and beauty and knowledge had become radically steeped in chaos and slaughter, and it was America that shone. It’s for this reason that I set Foreign Bodies in 1952, soon after the war (though it’s not an America without impurity, since this was the period of the McCarthy scares). And whatever one thinks of America today, including its history of chattel slavery, treatment of Native Americans, incarceration of Japanese-Americans, one truth remains: The Holocaust didn’t happen here. Still, to complicate things, the character who excoriates Europe in favor of America is far, far from admirable! So my intent was to turn Henry James’s theme upside down and inside out — though not simplistically.

What is the first book that really influenced you? How old were you when you read it?

Omitting childhood reading and its profound influences (the inspiring character of the writer Jo in Little Women, the eeriness of Alice in Wonderland, and masses of fairy tales above all), I believe my first moment of adult transcendence-through-reading came at age seventeen, when I discovered, in a science fiction [!] anthology my brother brought home from the public library, Henry James’s “The Beast in the Jungle,” a story long enough to be called a novella. I read it and thought: This is my life. The next year, when I was a freshman in college, E.M. Forster’s The Longest Journey was assigned in an English class, a novel I returned to time and time again over many decades.

Of all the female characters in your books, which one is closest to your heart? Which one resembles you the most?

Ruth Puttermesser, the hapless protagonist of The Puttermesser Papers. Though I have nothing else in common with her (she has never married, she is a failed lawyer, she manufactures a golem, she is brutally murdered), she is a bookish creature and sees the world through a literary lens, as (I fear) I sometimes do.

Will you ever publish the private diary you have kept since 1953?

No.

Will the Nobel ever go to another Jewish writer?

Possibly, and possibly to the extraordinary Israeli novelist A.B. Yehoshua (though I may be delusional to suppose this.) But not likely ever again to any American Jewish writer. To a European Jewish writer? Not unlikely, if (as we have already seen) the theme is Holocaust; entirely unlikely, if the theme has any positive affinities with Israel or Zionism.

Are you happy to be studied in US college courses on the Holocaust along with Primo Levi and Elie Wiesel?

I am always grateful to be read at all. But The Shawl, the little book in question, is a work of fiction, while Levi and Wiesel write as victims and witnesses. Their work has the power of document. I would be happier if some other novel of mine had attracted the interest of the academy, since I am not entitled to be regarded as “a Holocaust writer.”

Why did you keep “The Shawl” hidden for seven years? What did you think of Sidney Lumet’s direction of your play?

I kept it in a drawer because I felt it to be anomalous and not quite legitimate. Anomalous: It had come to me in a rush, as if “dictated,” a mystical notion I have always been quick to question. Not quite legitimate: It’s my belief that the documents have the greater power of truth-telling. After all, the Holocaust deniers have even accused Anne Frank’s Diary of being a fabrication. And much of the fiction based on the Holocaust has led to misrepresentation, fakery, and kitsch.

The play directed by Sidney Lumet, also called “The Shawl” (although out of town, prior to its New York production, it was titled “Blue Light”), was actually a sequel to, rather than an adaptation of, the book. Its theme was, in fact, Holocaust denial. Lumet’s two stagings were admirable.

In a recent interview, Don DeLillo told me that as long as there will be film, the novel will not die because the two are interchangeable.

Interchangeable?! I couldn’t disagree more. Film is always literal; the image is there before your eyes, the voices are in your ears, the interiors are meticulously furnished, a scene with water and trees will show you real water and real trees. You need imagine nothing; everything is given, it’s all a grand unalterable As is, it’s all a thinginess. Whereas a novel is yours for the making. It’s true that film technique has influenced the novel in certain stylistic ways; yet the novel is always, always free, and film is always, always limited to its one imposed eye, an eye that isn’t yours.

Is it true that the novel is in danger, as you say in The Din in the Head?

I’m afraid that was one miscreant reviewer’s mistaken reading. What I actually wrote was: “The novel has not withered; it holds on, held in the warmth of the hand. . . . Life — the inner life — is not in the production of story lines alone, or movies would suffice. The din in our heads, that relentless inward hum of fragility and hope and transcendence and dread — where, in an age of machines addressing crowds, and crowds mad for machines, can it be found? In the art of the novel, in the novel’s plasticity and elasticity. And nowhere else.”

Is your Italian translator Jewish? Should she be in order to fully comprehend your literature?

Whether the current translators into Italian of Foreign Bodies and Collected Storiesare Jewish, I have no idea. Other Italian translators in the past have not been. And how would it matter if they were or weren’t? When we read Nineteenth Century Russian novels and encounter such cultural oddities as, say, Name Days, and all those jaw-breaking patronymics, we aren’t deterred and somehow assimilate it all. The wonder of reading fiction is that we can enter scenes and perceptions that we could otherwise never penetrate. We are in debt to translators because they allow us to understand and feel for people and societies foreign to us. Translation’s blessing is that it unites; it does not divide.

Please cite the most important influences in your writing career; please give a full list of writers, dead or alive. Which newer, contemporary writers seem promising?

Of the classics, a fairly common and unsurprising list. E.M. Forster (especially A Passage to India); Henry James; Thomas Mann; George Eliot; Conrad (especially “The Secret Sharer”); Chekhov; Tolstoy (especially “The Death of Ivan Ilyich”); Lampedusa (The Leopard); Saul Bellow (whose collected letters I am currently reading and relishing). I believe John Updike is likely to last, both for his language and for his chronicling of certain aspects of mid-century American society; and I have belatedly begun to read A.S. Byatt, and think her extraordinary, heads above her contemporaries. For the most part, though, I tend to reread rather than become acquainted with newer writing.

Which of your contemporaries has been closest to writing the great American novel?

If being alive at the same time counts as being a “contemporary,” and if you will accept “a” rather than “the,” then Saul Bellow has already written a great American novel, twice, with The Adventures of Augie March and Herzog. Mailer, who loudly lusted after the “the,” failed even to achieve an “a.” And after all, there can be only one “the,” which some assign to Huckleberry Finn, and some to The Great Gatsby. If either of these deserves the solitary “the,” it seems the contest has already been declared closed.