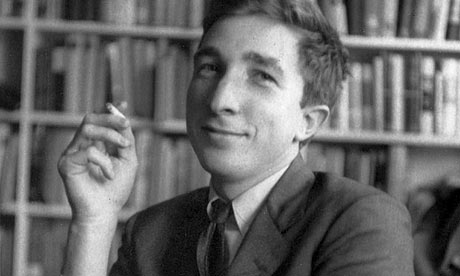

I campaigned in Reading, PA. This is Updike country: Reading was the model for the prosperous town of “Brewer” in his elegiac Rabbitquartet. It was built around the turn of the century, full of handsome neo-classical buildings, brick and stone. I went out into its streets with a crowd of eager volunteers. Our faces were fresh and enthusiastic, but Reading is no longer prosperous, and the faces we met were angry. They turned furious when I said who I was working for.

We met angry young men with little spirit patch beards, angry young men in construction clothes, angry middle-aged men in jeans and pot-bellied t-shirts. An older Army vet, his leg in a brace, shook his head when I told him who I was working for. A handsome older woman with long white hair down her back opened her door. “Democrats?” she said, her voice rising angrily. “No, no, we don’t want any of them here.” She slammed the door hard in my face. A well-dressed woman in her forties told me she’d already voted. “And did you vote for Hillary?” I asked hopefully. There was a little satisfaction in the shake of her head. “Trump,” she said, smug. The white man on the street wearing camo and an Australian outback hat, one side turned up jauntily like a big-game hunter, walking the mean streets of Reading. “Have you voted?” Joyce Hackett, my indefatigable partner, asked as we walked by. “No, I’m not voting,” he said, pleased that we’d asked. “Not voting for the first woman president? Crazy,” Joyce said cheerfully. We were past him by then. “And you’re assholes,” he said loudly. He expanded on this, his voice rising as he walked on. The two Eastern European women who told me shyly that yes, they were citizens, but they weren’t registered, they weren’t interested in politics. The wife of the Marine who said they didn’t like either choice and weren’t voting. The insurance broker with a little garden outside his door, for healthy choices. He’d watched his commissions go to zero with Obamacare. “I could tell you how to fix it in five minutes,” he said. “But they never fixed it.” “So who did you vote for?” I asked. “I threw my vote away,” he said, slightly abashed. “You didn’t vote third party?” I asked. He nodded. Over and over I was told why these people wouldn’t vote for our Democratic candidate. It was all the same reason. They hated us.

One volunteer, a young woman in her twenties, was walking down the little front yard from the house she’d just visited. In the next front yard stood a man holding a rifle. “You here for that bitch?” He asked. “I don’t want you next to my house or on my street. I want you out of here.”

I went out in the evening too, the last hour the polls were open, knocking on doors. The streets were dark. Not a single house had an outdoor light. The porches were unpainted, the concrete steps were broken. The sidewalks were uneven. There were no jobs. The people didn’t have green cards, they weren’t registered, they didn’t feel they knew enough to vote, their votes didn’t matter.

For them, the system was broken. My earnest explanation that the Republicans had been blocking the president’s initiatives meant nothing to them. Those streets were never cleaned. There were no jobs.

Once-prosperous Reading is now the fifth poorest city in the country. The handsome row houses are falling down, the pillars covered in peeling paint, windows boarded up, railings are shaky or missing. That confident middle America that John Updike knew is gone, its steps broken, the roof patched. I don’t know who will fix it, but liberal Democrats didn’t manage to do it in eight years.

These people have been buried by the rubble from a landslide of unregulated capitalism. We thought they understood that we were working our way toward them, digging to find them, like survivors of an earthquake. They thought we’d forgotten them, left them buried alive. They’d shouted for help, and thought we’d abandoned them, and were inside having dinner. They wanted to live.

We understood the rage felt by some people, but not its depth or range. Now we have been made to understand how deep and far it runs. Now it’s up to us to understand these people more clearly, just as we wanted them to understand us. We wanted them to become part of our nation, thinking that would improve their lives, but it didn’t. So now we must become part of their nation, whatever that means.

It’s our task to make it mean something positive. We’re in this together.

–Roxana Robinson