From the award-winning poet and playwright behind Barber Shop Chronicles, The Half-God of Rainfall is an epic story and a lyrical exploration of pride, power, and female revenge. In the following essay, author Inua Ellams reflects on his experience writing the book, which is available for purchase through our online bookstore.

The Half-God of Rainfall is a many-layered thing and has been described as an epic revenge fantasy on love and basketball, a meditation on power and patriarchy, a black feminist response to the #MeToo movement, Nigeria’s answer to Marvel’s Avengers, and a feature film waiting to happen.

A friend described it as “a love-letter to lone parenting,” and it is also definitely that. It explores the extensive lengths to which a mother goes to protect her son from his abusive father—an unfortunately ubiquitous global occurrence. However, in my poem, “Modupe,” the mother is a mortal woman. Demi, her son, is an athlete, and the father is Zeus. The story starts on a grassy patchy basketball court in South-West Nigeria and ends with the complete obliteration of Mount Olympus. It mixes Yoruba with Greek Mythology, basketball urban-lore with spiritual belief, and Homeric aesthetic with sporting hysteria. The story is huge, mammoth, but it began in a much simpler, humbler way.

When I was 12 years old, my family and I moved to London, and I started playing basketball because a girl I was enamored with loved the sport. I figured the only way I could be in her eye-line was to be the one with the ball. I had no skills whatsoever but believed in the possibility of genetic mutation—that I could achieve the impossible and defy the laws of physics, just like the X-Men.

Years before, in boarding school in Nigeria, at night by flashlight, I’d read the Marvel comics smuggled between dormitories like sacred contraband and dream of their epic battles. I’d wake up to Nigeria’s cloudless sky, take in its borderless-ness and believe, just like Storm, I could reach into it.

Back on the courts in London, I’d will latent mutant genes to unlock my abilities and manifest as I shot the ball. Those powers would mean I’d never miss a shot, and the ball would swish smoothly through the hoop. I played enthusiastically for the three years I spent in London before I moved to Ireland.

I quickly discovered I was the only African boy in the entire student body. The school was drowning in racism, the scope and fever of which was only matched by ignorance. The safest space for me was the basketball court, among the school’s all-white, all-Irish basketball team. They assumed that, because of my skin color, I would have an encyclopedic knowledge of hip-hop culture and a natural ability to dominate the game. On and off the court, I felt the pressure to represent the best Africa and people of African descent. I know now how astonishingly ludicrous a weight it is to carry, or to imagine carrying, but back then I felt the entire student body watching and judging my every move. I didn’t just have to be the good immigrant, but the infallible best.

After a few games and months of solid basketball drills and progress, my boys convinced me to try out for the local team. The coach was the legendary Jago, a big man in his early thirties who had a charming, older-brotherly style to coaching. The session began. I darted down the court, keeping pace with the opposing team until they scored a simple two-point layup and the ball was in my hands. I dribbled down the right side, crossed over to lose the man marking me and, way too far from the rim, gathered all my strength, willed my mutant genes to manifest yet again, took a shot and watched the ball soar.

After the game Jago divided us into two groups. “Sorry lads, yous weren’t quite good enough, but keep practicing for next time, eh?” He pointed to the group I was in and smiled: “Yous are in,” he winked at me, “nice shot.”

I made the team. I was loosely assigned the position of small forward when we were on offense. On defense, my job was to bother the hell out of the point guard. The point guard’s job is to bring the ball down the court and call out the team’s strategy to score. Jago could count on me to never tire, to keep running throughout an entire game and force point guards to make mistakes. I was so good at this, I once frustrated a point guard until he punched me and was ejected from the game. Jago simply smiled as I sat down on the bench.

In my final year in Dublin, I stopped being able to play; I remain baffled to this day. In a single week I went from being the fastest and most restless on the team, to wheezing and clutching my chest when I jogged. My legs stopped doing things my brain asked them to do. I would only jump half as high as I had done the week before. Jago advised me to check it out and the doctor diagnosed me with exercise-induced asthma. It developed out of nothing. I could no longer trust my body. It felt like the worst kind of betrayal and the latent mutant-gene-fantasy seemed even more foolish.

Seven years later, I was back in London writing and performing poetry. On Wednesdays, I attended the late great poet Roddy Lumsden’s class. One evening I shared a poem called “Of All The Boys of Plateau-Private School,” about a couple of knuckleheads I played with in Nigeria. The poem included these lines about a friend called ‘T’:

T could spit faster than fleas skip, further than lizards leap, spit so high, we claimed him / Herculean in form, the half-god of rainfall . . .

Roddy loved that line, that final image, a half-god, half-mortal, a superhuman who could command rain to fall. On the way home, I thought about it. I remembered that in basketball, if you could shoot well, if you could rain down shots, you’d be called a ‘rain man.’ I woke up the next morning and a character was forming . . . a superhuman basketball player, who could score impossible shots, who could do the things I had never been able to. I started writing the story then, but, essentially, I had been writing it my whole life. I had been trying to be him. He could now be the half-god of rainfall. I chose to call him ‘Demi’ not only because it meant ‘half,’ but ‘Demi’ was also a Nigerian name—he would have to be Nigerian, naturally. He would have started playing ball in Nigeria, but as I lived in England and wanted him to reflect my reality, he would have to have ties to England. Perhaps his godfather could represent this cultural heritage? Maybe Zeus? Had to be Zeus. Who else?

I started looking into Zeus as a father-figure. As I read, I found countless articles, essays, and critical studies that concluded, without a doubt, Zeus was and had always been a sexual predator, a serial rapist and a violent, vengeful, callous God. Having discovered this, I could not unlearn it. I had a choice to make: write the nice story about a Nigerian basketball player or write about Zeus and tell his unfettered truth. I chose the far harder option—to do both in the same story. I had to start all over again.

It took seven drafts and eight years to complete . . . years of reading, writing, and re-writing, during which many aspects of my personhood changed many times over, causing me to change Demi’s journey and introduce new complications into his life.

Each discovery meant a re-write, and each re-write sent me questioning my relationship with my three sisters, my girlfriends, my lovers, my parents (particularly my mother), societal gender constructs and norms, the prevalence of sexual harassment, domestic violence, law, rape and rape-culture, incels, rape convictions, feminist theory, masculinity, power and propaganda, male privilege, black male privilege, euro-patriarchal knowledge production, the knowledge industry, the sports industry, sports journalism, European education, censorship in education, pre- and post-colonial educational policy, Africa’s exodus—the great brain drain, U.S. and British immigration policy, how I ended up leaving and living in England in the first place . . . it sent me questioning every aspect of my life.

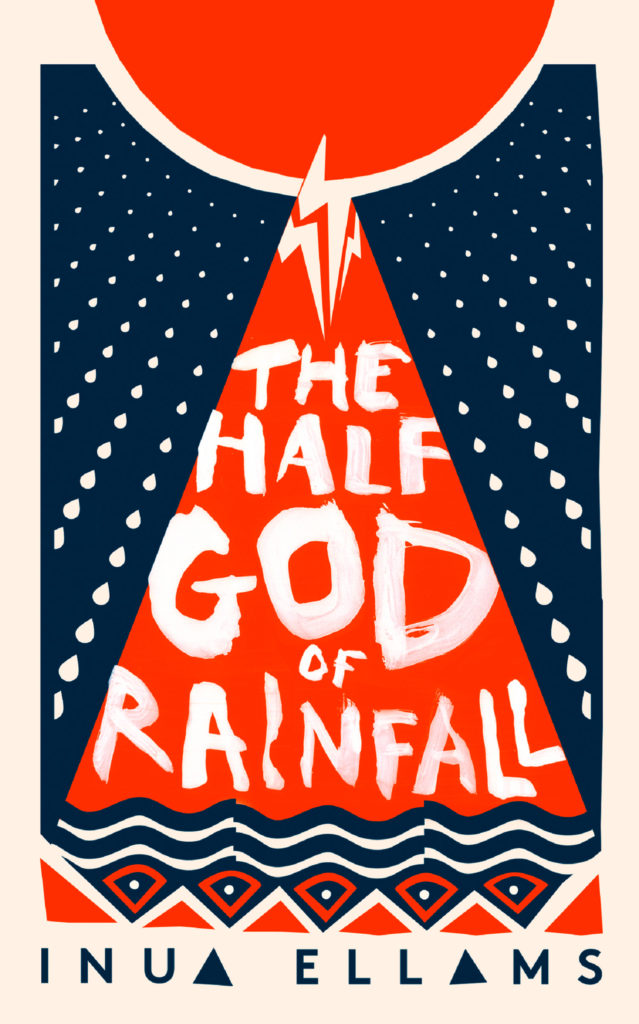

Featured Book

-

.

The Half-God of Rainfall

By Inua Ellams

Published by Fourth Estate

There is something about Demi. When this boy is angry, rain clouds gather. When he cries, rivers burst their banks and the first time he takes a shot on a basketball court, the deities of the land take note.

His mother, Modupe, looks on with a mixture of pride and worry. From close encounters, she knows Gods often act like men: the same fragile egos, the same unpredictable fury and the same sense of entitlement to the bodies of mortals.

She will sacrifice everything to protect her son, but she knows the Gods will one day tire of sports fans, their fickle allegiances and misdirected prayers. When that moment comes, it won’t matter how special he is. Only the women in Demi’s life, the mothers, daughters and Goddesses, will stand between him and a lightning bolt.