Once there was a child who hid from her father. She imagined him with blades for hands, she saw herself as strung on a leash that he owned. She was afraid, but she was eight years old and there was nowhere she could go or hide, except in the closet, where she would eventually be found. But she discovered that books were other houses to hide in, and when you read a book, you were no longer you. You were no longer an immigrant in California struck dumb by language, you were no longer a young girl. She did not ask herself if fiction mattered, but she read fiction as if it mattered. Fiction saves lives, she wrote in firmly printed letters in her diary (she had not learned cursive yet) and underlined those words. This is a true story, though the stories she wrote later when she grew up were not true, at least not in the prosaic sense.

Our hunger for facts. The most uncomfortable question that readers sometimes ask of a writer is, “Is it true?” which also means, are you the character who slept with her father? Or, the one who cut herself? I am being asked to verify a salacious fact, as if a short story collection were another form of tabloid reading when “truth” may be more than just the facts. I am more interested in what C.S. Lewis had to say about truth: “For me, reason is the natural organ of truth; but imagination is the organ of meaning. Imagination, producing new metaphors or revivifying old, is not the cause of truth, but its condition. It is, I confess, undeniable that such a view indirectly implies a kind of truth or rightness in the imagination itself.”

***

In Rome, I cannot say anything. In my first month living in the city, I wandered the cobblestone streets of the Trastevere neighborhood and was struck dumb. I didn’t even have access to the language of facts. When I tried to speak basic Italian in a café, the barista with a shaved head and the build of a middleweight boxer said curtly, “Speak English!” I am in Rome for one year, thanks to the American Academy in Rome, and I will soon learn that not all baristas are so unkind. But not yet. At this point I am trying only to understand the who, what, when, where, and why of my environment. I go into bookstores and optimistically buy Italian novels that I cannot read, for the distant future. Words have become pictures. Silent, silenced, my verbs, nouns, and adjectives are estranged from each other and become plaster fragments. The words will not speak.

I’ve read and read, and been replenished by the years of reading. I have become a writer.

In Francesca Marciano’s short story “The Other Language”, the main character Emma’s life begins to change during a summer spent in a Greek village where she meets two English boys and slowly inhabits the new language of English as well as the language of love. It was a summer of possibility where she “landed in a place where she could be different from whom she assumed she was.” And it was language that took her there; “The other language was the boat she fled on.”

Gaining command in the new language is what allows Emma to imagine a new self that in the broad time frame of the short story becomes an actualized other. As for myself, I know the present tense in Italian and am familiar with the simple past, but I do not know the future tense yet. I have around fifty verbs that I understand. I know how to say “I’m hungry” but not “We are hungry creatures.” And because of that, I am altered to myself and to others. Emma thought that she became a different kind of person with language, and maybe this is true. But she also became the kind of person that she had imagined, desired, and worked toward being.

I see that in myself when I live in Seoul and speak Korean. I see myself traveling through language toward a desired—or more desirable—image of myself, a better version of my English self, through language, for the invention of the self is another kind of fiction. There are so many fictions. The fiction we read and write. The fictions we tell ourselves, sometimes, in order to keep going, rendered so aptly in Samuel Beckett’s novel The Unnamable: “You must go on, I can’t go on, I’ll go on.” The fictionalizing of ourselves, and beyond that, the fictionalizing of the past that so many countries are guilty of.

***

It must be obvious. I am—or was—the girl in this essay’s first paragraph. Many things have happened to me since then. I escaped that house, then went on to live in many other houses on three continents. I have lost two cities, and then lost farther, faster, and somewhat mastered Elizabeth Bishop’s art of losing. I’ve ridden on the tops of trains, the bristly backs of elephants, had a toucan pee on my head, and dreamed, repeatedly, of being homeless. I have spent the greater part of my life being afraid, then being angry. I’ve read and read, and been replenished by the years of reading. I have become a writer.

Faced with the task at hand, I think of how Anton Chekhov once said that the artist’s role is to ask questions, not answer them. I’m also reminded of the last stanza in Emily Dickinson’s poem “I’m Nobody! Who are you?”:

How dreary – to be – Somebody!

How public – like a Frog –

To tell one’s name – the livelong June –

To an admiring Bog!

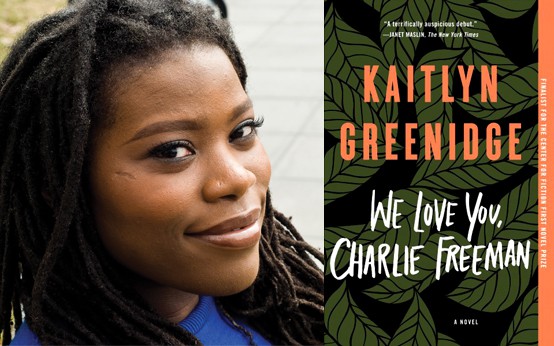

Trying to address the question of why fiction matters feels a bit like standing in public and croaking like Dickinson’s frog. And to be truthful, I ask myself less does fiction matter, than why do I write? But in the end, both questions may mean the same thing. Here is a necklace of the obvious, the string of charms that I trust: Fiction teaches us empathy (how I dislike the declarative sentence). The very nature of fiction is magical. You are both present yet elsewhere in space and time. You are a man, a woman, a grandmother, an ape, a charismatic pedophile. Fiction is a discovery of a new language. For someone like Scottish writer Kerry Hudson, fiction is a second chance, a mission. Fiction is not just a genre: It’s a way of inhabiting. It’s an attempt to wrestle away language from the traditional bastions of power from writer to writer, book to book, and have it transform us. It’s a way of understanding our world.

The best fiction raises questions, creates shadows, brings to relief the uneasiness in us.

This much I’m sure of. The best fiction is different. It combats our hunger for facts and clarity and reveals most clearly how ambiguous are all our institutions, beliefs, our very selves. The solidity of us is thrown into relief and questioned. When an intelligent critic tries to articulate and give expression to the fictional world, that intelligent analysis will also feel somehow reductive. The best fiction raises questions, creates shadows, brings to relief the uneasiness in us. Jun’ichirō Tanizaki said that it is those shadows that create, and allow, beauty to exist. It is this very ambiguity of fiction, its discomforting unveiling of pat answers and easy delineations, that allows us to inhabit the space that George Saunders called the space of “non-knowing.”

***

In a talk given at the Yonsei University-Kim Dae Jung Forum held in Seoul, the Nobel Prize recipient of Literature Kenzaburō Ōe argued that a new image creates a new story. I asked myself later, then is the reverse also true? Do the ancient images allow for timeless stories? I return repeatedly to the image of Babel, the tower built by all of humanity that was once able to understand each other in a single unified language. This power to communicate unimpeded was so threatening and dangerous to God that he responded by saying, “Behold, the people is one, and they have all one language; and this they begin to do: and now nothing will be restrained from them, which they have imagined to do.” The tower had to be destroyed so the language was corrupted and confused into many languages, and the people were divided from one another. Since then we have been trying to piece together those mythic fragments and create with them a broken whole. Those pieces of language, I call story.

Fiction matters because, to my relief, it is greater than any single writer. It is the variegated choral voice that finally rises above the individual ego, the confines of present time and space, into a kind of Tower of Babel that looks something like: Listen: this is what we heard.