What I am is tormented. Back and forth. Not capable. Not worthy. No time could be enough. My reverence has me sprawled. What I want is to do justice to writing about Tell Me a Riddle.

Reverence is not the right word. Too measly, for one. Also, too religious-sounding for Tillie Olsen, whose character in “Tell Me a Riddle” insisted her hospital chart read Race: Human, Religion: None.

“I Stand Here Ironing,” a short story in Tell Me a Riddle, to me (and many, many others, I am sure) is the perfect story. From the first line “I stand here ironing, and what you asked me moves tormented back and forth with the iron,” the experimental, poetic language tells the story of loving a child, of having to leave her alone, of having to work, of feeling that “I will never total it all.” It is a story to read over and over to reconsider sentences like “She was a miracle to me, but when she was eight months I had to leave her daytimes with the woman downstairs to whom she was no miracle at all, for I worked or looked for work and for Emily’s father, who could ‘no longer endure’ (he wrote in his good-bye note) ‘sharing want with us.’” At the end, though, my heart thuds down when the narrator states “So all in her will not bloom—but in how many does it?” How many indeed?

The first time I met Tillie Olsen, I cried.

She was in New York to see Pete Seeger and had asked me to meet her at her hotel on the Upper West Side.

As soon as I stepped across the threshold of the hotel, I broke down. Since it came as a complete surprise, I did not know what to do. I was doubled over and steadied myself just inside the door. Thankfully, no one else was in the lobby.

I slipped back outside to the crowded street. People stared. I covered my face and searched for a place, any place, I could hide. The sobbing would not stop. Embarrassing, gulping in of air, my shoulders jerking up and down. I knew it would be one of those cries that would leave my face splotched with red areas. I had to stop. After all, I couldn’t be late to meet Tillie Olsen.

I walked a bit. What is wrong with me? I thought. I’ve met famous people before, haven’t I? But, well, I had to admit, Tillie was not just a famous person. She wrote the story that had inspired me, changed my life, the story I go to in my darkest moments. And no famous person had ever asked to meet me before. I returned to the hotel and inquired at the front desk.

“She is expecting you,” the man said, “Go on up.”

I wanted to say, “Do you know who she is?” but I only nodded, afraid any words would start the crying again. I found a bathroom, splashed cold water on my face. I’m okay now, I thought in the elevator. The door was open. I knocked. “Come in,” someone said. As soon as I stepped in the room, I started crying again.

“Don’t worry,” a woman I would soon learn was Alix Kates Shulman, said, “I cried too when I first met Tillie.”

On that visit, Tillie Olsen told me how she had worked as a housekeeper in a hotel and so took the newspapers out of the rooms. She saw an ad for a short story contest. “I have one,” she thought, and sent off “I Stand Here Ironing.” She said she took out a middle page because she thought it wasn’t so good. Months later, she said, Wallace Stegner called her, telling her she had won the Creative Writing Fellowship Award and he wanted to welcome her to the Graduate Creative Writing Program at Stanford University. “Is it okay I didn’t finish the eleventh grade?” she asked.

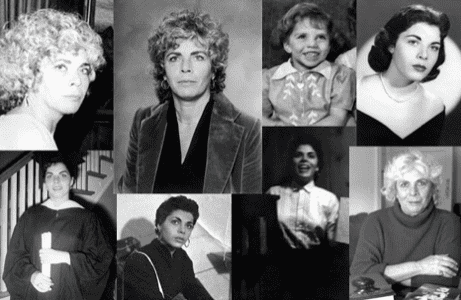

Tillie Olsen’s life is well documented in countless interviews, books, and scholarly journals. How her parents, Samuel and Ida Lerner, came from Russia in 1905 to settle in Nebraska, how her father was the State Secretary of the Nebraska Socialist Party, her mother intellectually and politically astute despite illiteracy, how Tillie Lerner joined the Young Socialist Party and the Young Communist Party, how she was jailed for distributing leaflets at a packinghouse, how she discovered in a rummage sale bin an Atlantic Monthly magazine from April 1861 that contained Rebecca Harding Davis’s “Life in the Iron Mills,” which opened up the idea of writing from her own working class life. How she went to Minnesota after a bout of tuberculosis and began writing Yonnondio, how she had a child at nineteen, how her story, “The Iron Throat” published in Partisan Review (1934) brought her national attention and a book contract, how she left her daughter with relatives to write in California, then reunited with her daughter, moved to San Francisco where she wrote “The Strike,” an early example of reportage about the Longshoreman’s strike that ended in a Bloody Thursday massacre, and how she met and married longshoreman Jack Olsen and had three more children. Many years later came the Stanford Fellowship, a Guggenheim, Radcliffe Award, MacDowell residency, the publication of Tell Me a Riddle in 1963, Silences in 1972, Yonnondio: From the Thirties in 1974, her work to re-publish Rebecca Harding Davis and many other women writers at the Feminist Press, a life active in anti-apartheid, anti-war, anti-nuclear and other causes, and her generous support of other writers, including me.

“Strike,” included in Tell Me a Riddle, Requa 1 and Other Works, begins “Do not ask me to write of the strike and the terror. I am on a battlefield, and the increasing stench and smoke sting the eyes so it is impossible to turn them back into the past” and in contrapuntal reportage tells of the events of the Longshoreman’s Strike of 1934. In Tell Me a Riddle, “Hey Sailor, What Ship?” portrays a sailor compassionately as a person suffering from the disease of alcoholism. In “Tell Me a Riddle,” the old man calls the old woman “Mrs. Word Mizer,” when she refuses to go to The Haven, a home he says has a reading circle. She answers: “Now, when it pleases you, you find a reading circle for me. And forty years ago when the children were morsels and there was a Circle, did you stay home with them once so I could go? Even once? You trained me well. I do not need others to enjoy. Others!”

He mocks her, calling her “Mrs. Enlightened,” “Mrs. Cultured,” “Mrs. Live Alone and Like It,” Mrs. Free as a Bird,” “Mrs. Telepathy,” “Mrs. Excited Over Nothing,” but, in the end, “Nighttimes her hand reached across the bed to hold his.” “Requa,” first published in The Iowa Review in 1970 is perhaps Olsen’s most experimental writing that zips along in logging country in northern California, zig-zagging between three narrators.

I think I know why I cried so hard the first time I met Tillie Olsen. It was not for her, though I cannot imagine who I could respect and admire more.

It was for the impossibility, in all the chaos, that such a work of art as “I Stand Here Ironing” could even exist. I cried for all the culmination of chance events, all the wrong and right turns, the happenstances, the recognition of the importance of what is, the immediate and deliberate decisions, the random bits of conversation, the crossing of paths, the unlikely encounters, the impossibility of the discovery of a forty-year old magazine in a flea market bin, the books that happened to be in a particular library at a precise moment Tillie Olsen happened by, the accumulated consciousness, the ruminations, the overcoming, the struggle for time, the utter unlikelihood and impossibility of all the moments and memories coalescing, lining up, and becoming the words on paper that became the collection of stories Tell Me a Riddle.

That is why I cried. Because it surely could not be and yet it is.