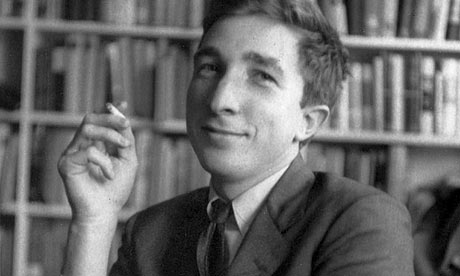

I don’t know when I started reading John Updike, but it was probably when I was in my teens. I sank into his beautiful prose as though it were a summer-high meadow. I hadn’t known you could write like that. I hadn’t known you could use language so precise and elegant, or speak from a heart so compassionate and generous, or reveal life that was so daily and so unpretentious, so authentic.

For years I read every story he wrote. They seemed essential. They seemed what writing should be. They showed that this was the way to look at the world, with a gaze that was thoughtful, attentive and generous. The generosity was what moved me most, and it seemed that Updike was the true heir to Chekhov, a writer who accepted every kind of behaviour—selfish, stupid, arrogant, tender, wounded, idealistic, wise, brave, brutal, loving—as part of the human story.

Years ago, while teaching a writing class, I told my students that the best way to learn to write well was by reading good writing. If I can write, I told them, it’s because John Updike taught me.

After class, a student came up to me. Have you ever told John Updike that he taught you to write? She asked.

I told her I had not.

You should, she said.

When my next book came out, a collection of stories, I sent a copy to Updike. In a letter I explained what my student had said, and told him of my debt.

He wrote back at once, a type-written post card.

“What a nice letter,” he wrote, “I’ve never had the impression of influencing anybody, actually. Leslie Fiedler once described me as a ‘curiously irrelevant’ writer, and I’ve poked along my lonely road ever since, shouldering irrelevancy with more or less good cheer. Now you say I’ve been relevant to you, and it’s made my day.”

It made my day to get his post card, which I framed.

I kept on reading his stories and novels, which seemed to illuminate our lives. Who else was looking so closely at the way we really lived? Who else was so tolerant of our frailties, so aware of our vulnerabilities, so interested by our failures, so respectful of our passions? Who else wrote such breathtakingly beautiful prose? I sent him a copy of the next book I wrote, but didn’t receive another post card.

A few years later I met my hero face to face. It was at a literary party, and I saw him standing alone. It was my moment. I drew a deep breath and walked up and introduced myself.

My conversation with him had been going on throughout the whole of my writing life. I read his stories, I taught them, I remembered characters and scenes and phrases, I carried his sentences around in my mind. My understanding of marriage and divorce and parenthood was influenced by the way Updike had rendered them. I felt a certain kind of tenderness towards husbands and wives and children, because of the way he had written about them. I felt his constant presence in my world.

That evening I told him who I was. I reminded him of my letter, his postcard, my book of stories. He smiled, that courtly V-shaped smile we know so well from the photographs. I could see that he had no recollection of our conversation, of my book or the post card with his kindly response. I had been thinking about him for twenty years. He had never thought of me.

What have you done since then? He asked politely. Have you published anything else?

I had published several books since then, but I was unable to answer.

I had been thinking of him for twenty years, and he had never thought once of me, he had never read any of my books or even heard of them, and suddenly the extreme one-sidedness of our conversation was too much for me.

I’m sorry, I said, I can’t talk to you any more. I turned away.

I wanted, of course, to continue our conversation, but it was better to continue it in the way we’d always done it before—me thinking of him when I was alone, and reading his work. This was better than trying to carry it on at a party, when only one of us even knew about it.

I walked away that night, never imagining that it would be our only meeting. I thought of course we’d have another chance, and this time I’d be better prepared, or that he would. Maybe he’d have read something I’d written, or maybe I’d be able, this time, to start another conversation.

But maybe the real conversation between writers was the longstanding one we’d always had, the one in which I read each of his words, alone, encountering them deep in privacy and silence, which is the best way to meet another writer. It was a conversation for which I was profoundly grateful.

In a century famous for irony, for disaffection, for cynicism, for bitterness, for existentialism, for surrealism, for post-modernism and metafiction, for literary currents that favored experimental approaches to form over emotional connections between people, Updike remained steadfast to the literary institution of humanism. He wrote in the tradition of Homer, Shakespeare, Tolstoy, Woolf; he was the greatest American writer of the twentieth century.

Great fiction is about the power and complexity of human engagement. Updike understood the glowing bond that links people so irrevocably, he understood the costs and the rewards of this deep linking, and he revealed all this in nuanced, powerful and exquisite prose. It’s rare for a writer to combine, in such sumptuous abundance, the gifts of wisdom, grace and caritas.

We were lucky to have him. We were lucky to have all those stories, those novels, dropped so quietly into our collective unconscious. We were lucky to be part of a conversation, however one-sided, which, for five decades, offered us new ways to understand the lives we were living.