An archaeologist friend told me recently about the discovery of an oral tradition stretching back for 10,000 years.

They were stories told by Australian aboriginals, set on the great grazing-grounds of a plain near Melbourne. This was a group of related narratives, about the landscape and the animals and people who lived there. They were stories about kangaroos and wallabies, about where they grazed and where they bred, about the life they led on that plain, and about the life of the people who lived there with them. The stories of the animals and the people were deeply interconnected. The sites they described—the plain, and the grazing-ground with its low hills—were all named, and all identifiable. Everything is still there. The curious thing is that it has all been underwater for over 9,000 years. The hills are now islands, and the grazing ground is Melbourne Bay.

Those stories were handed down for some 400 generations. Oral history isn’t always so reliable, but these narratives were kept intact because they were essential to the survival of the people who told them. Without the stories, how would they know where they were in the world, or how to live there?

Maybe science has just discovered the importance of narrative, but I don’t think it’s news. We humans are hard-wired for story. It’s how we learn to be in the world.

As infants, our first response to the world is solipsistic, but once we begin watching others and engaging with them, we start to learn through an intimate form of narrative. We do this by observation and by empathy.

The first stories we learn are short ones, from our parents. Your mother tells you what she’s done, or maybe you watch her do it: She puts salt instead of sugar in the cake batter. When she realizes it, she laughs, and says what an idiot I am. This is how you learn what happens when you make a mistake. You learn that it’s not a catastrophe, that resilience is the proper response, and that the world is a pleasant place. Or you see that someone is rude to your mother in the supermarket, and you watch her face turn dark and anxious. Later, when she tells the story, she says she wanted to kill the checkout girl. This is how you learn that people are threatening, your mother is vulnerable, and the world is dangerous. We learn these narratives long before we can read. It’s through them that we begin learning how to live in the world. Like the aboriginal stories, these are essential. We need to learn where safety lies, and where we are at risk. We need to learn the difference between rage and laughter on our mother’s face.

Stories are about feeling; it’s through feeling that we learn about the world.

Narrative is more than anecdote, it does more than merely relate an event. Narrative contains meaning: This is what happened, and this is what it means. We watch our parents’ faces to see how to respond, to see what it means. The only way we can learn this is by recognizing the feelings they express, and by entering into those feelings. Through empathy. Stories are about feeling; it’s through feeling that we learn about the world.

Even if you don’t read fiction, you’ve grown up depending on narrative. You live with stories, you always have.

As a child, you were read fairy tales, stories about children like you. The boy who chopped down the beanstalk, the girl who left a trail of bread crumbs to mark the way home. The girl who had to sleep in the fireplace but who then married a prince. Those stories instruct children to be virtuous and brave, loyal and patient and kind. The instruction works through empathy: We identify with the hero, or heroine, so the lesson is printed indelibly on our minds. We feel the story happened to us. We know for certain we’d have tricked that giant, chopped down that beanstalk, dropped those bread-crumbs in a careful line on the forest path. We’d have been kind and virtuous and uncomplaining, and our little foot would have slid easily into that glass slipper. Empathy for the character is what fiction encourages, in fact it’s the whole point.

But now we’re adults, and we know everything. We know how to read our parents’ faces. We’ve done it a million times; we know what delights them and what threatens them. We know what those encounters mean, we know how to read the world. We don’t need to read fiction. We’ve learned everything we need to know from narrative. We’ve finished with empathizing.

We live in a hard, fact-based world, one that runs on grids and electronics and data. Maybe now fiction is peripheral, ancillary, not really central. In a culture governed by technology and cyber-reality, do we really need it? All that empathy and cultural perception?

Let’s imagine the world without it.

We’d have to get rid of the Bible, to start with. Whatever you believe about its origins, you know it’s not scientific and fact-based. It’s made up of unverifiable information that comes from uncheckable sources.

The Bible is made up of stories: fiction. These offer ways to interpret the world, to understand why we’re alive and to plumb the depths of our own experience. These stories relate to the spiritual realm, but also to the temporal, quotidian world of families, failings, loves, and rages. The stories are about weather and crops, feuds and lies, adultery and constancy, revenge and forgiveness. A lot of them are about love, in its many manifestations—filial, erotic, fraternal, jealous—every kind. The Bible is not an abstract philosophical text, it’s a vast web of interconnected stories about human beings and how they act. This narrative web has been the vehicle for Christianity for two thousand years. It’s one of fiction’s masterpieces.

If fiction doesn’t matter we’ll also have to get rid of the classical texts. The Iliad, for example, told in the form of narrative poetry. This is the great story of war between the Greeks and the Trojans, and it’s instructive on many levels, like all great fiction. It’s a historical source for the period, informing us about the way people dressed and ate, the weapons they used, the chariots they drove, the way in which they waged battles, how warriors fought and worshipped and mourned.

It’s not just the ancient narratives that are useful. I once spent time at the National Humanities Center, which offers fellowships to scholars from all over the world. A German scholar was there, doing work on a 19th century writer. One day I asked him what the most useful tool was for historical research. I expected him to name sources of hard data: church records, or property transfers, or harvest yields.

“Novels,” he said at once.

“Really?” I said, delighted.

“Of course,” he said. “They give you a record of the way a society really functioned. Everything is laid out there: clothes, meals, marriage, family, everything. It’s all in the novels.”

This gave me a wonderful feeling, because of course I myself am a novelist, and this made me feel as though I might be making an important contribution to cultural studies, and not just making things up inside my head.

After that I pictured the great novels like large, handsome doll houses, lit from within, and with roofs that could be lifted up for us to look inside. We could peer in and see the whole household, with carpets and chairs and four-poster beds, a maid hurrying upstairs, a fire burning in the grate and someone knocking on the front door. There were books on the shelves, clothes in the closets, dinner on the table and pictures on the wall, and everything, everything, down to the smallest detail, was true and real and perfect. Life was being carried out there, right before our eyes. We could lift the lids on these flawless, intricate constructions and enter into them whenever we wished. It was a miraculous luxury.

We can learn about life in the 19th century from Bronte and Austen, Dickens and Trollope, Tolstoy and Flaubert and Wharton. The great novelists tell us exactly what it sounded like, walking through a small town in France, and how the Yorkshire moors smelled in springtime, and what the mean streets of London looked like. What servants worked in the household of a wealthy Muscovite, what a New York bachelor’s flat looked like.

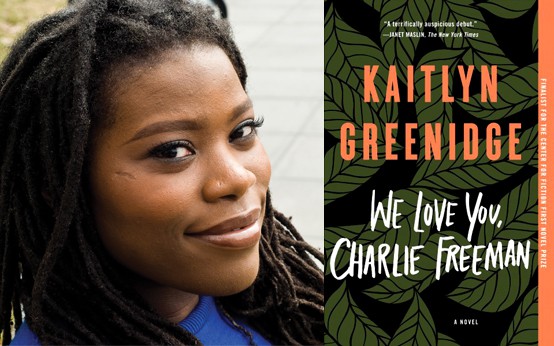

We learn about the 20th century from Woolf and Proust, Hemingway and Updike and Munro. We’re learning about the 21st century from Egan and Ferrante and Knausgaard, and who knows who else will instruct us? It’s fiction that will deliver the true idioms and rhythms of the times, how people talk and dress, how they use certain words, how fast people walk on the street, what time they eat dinner, and who irons the tablecloth.

So fiction matters a lot, in some ways. It’s essential for our understanding of the world, as children; it’s essential to Christian heritage and it’s an important cultural resource. But what if we’re not children or Christians or scholars? Anyway, all that lies in the past, and maybe the past is not so relevant today. Today is already nearly the future, when we can communicate over thousands of miles with the swipe of a fingertip, records are kept of everything and all facts are available forever, and data has overtaken us. Maybe there’s no need for fictional narratives to create a historical record that can be mined in the future.

Does fiction matter now?

This brings us to the heart of things. The real reason that fiction matters is not because of history or religion, but because of the life of the emotions. Fiction offers us a way to enter into someone else’s emotional life, and, no matter how deeply into the future we have penetrated, entering into someone else’s emotional life will always be crucial. Empathy is an essential part of being human.

Another recent study (I’m offering hard data, to convince you scientists and scholars; I think you fiction readers already agree with me) shows that people who read literary fiction become more empathetic than those who read nonfiction, or popular or genre fiction. Interestingly, it isn’t just any fiction that will make this change happen, it’s only literary fiction. My own definition of this form is fiction that’s complex and engaging, well-wrought and demanding. It’s fiction that’s intended to offer something greater than entertainment or information. All great fiction falls within this category, so it’s really great fiction we’re discussing. And reading it will actually change your character. It will make you more adept at understanding other people.

Beauty offers us a portal into another way of being. It causes that indrawn breath, that reminder of a mysterious part of the world that we’d forgotten. A perfectly wrought sentence, a masterpiece on its own, enlarges us.

There’s also the matter of beauty: A kind of beauty is inherent in all great fiction. Sometimes it’s present in the language itself, in the attentive placement of words. The sentence itself becomes like a piece of jewelry, perfectly made, a series of polished links glittering with gems. Here’s the opening of a novel:

“By nightfall, the headlines would be reporting devastation.

It was simply that the sky, on a shadeless day, suddenly lowered itself like an awning. Purple silence petrified the limbs of trees and stood crops upright in the fields like hair on end. Whatever there was of fresh white paint sprang out from downs or dunes, or lacerated a roadside with a streak of fencing. This occurred shortly after midday on a summer Monday in the south of England.”

This language, with its brilliance and precision, its absolute authority, is itself electrifying. Through this closely-observed description we learn that the world we are about to enter is always vulnerable, meteorology is a powerful presence, and that the heavens may erupt at any moment. All these things will be important: This is the beginning of Shirley Hazzard’s masterful novel, Transit of Venus, one of the best books of the 20th century.

Another opening:

“His children are falling from the sky. He watches from horseback, acres of England stretching behind him; they drop, gilt-winged, each with a blood-filled gaze. Grace Cromwell hovers in thin air. She is silent when she takes her prey, silent as she glides to his fist. But the sounds she makes then, the rustle of feathers and the creak, the sigh and riffle of pinion, the small cluck-cluck from her throat, these are sounds of recognition, intimate, daughterly, almost disapproving. Her breast is gore-streaked and flesh clings to her claws.”

The command of language and imagery here is also masterful. The meaning of this passage is deliberately obscure, and requires our close and respectful attention. It is only by inference that we learn that these children must be raptors, birds of prey. By inference we learn that this story will be about loss, family, premeditated destruction, gore and murder. And so it is: This is the opening of Hilary Mantel’s great historical novel about Thomas Cromwell, Bring Up the Bodies.

All beauty is transformative; we need it in our lives. Beauty offers us a portal into another way of being. It causes that indrawn breath, that reminder of a mysterious part of the world that we’d forgotten. A perfectly wrought sentence, a masterpiece on its own, enlarges us.

Sometimes we can only read a work in translation, and we’ll miss that perfectly wrought sentence. We can’t see it, but we know beauty is there. Its presence informs the text, flickering beyond it like the shadow of a flame. All great fiction contains a kind of metaphysical beauty, a widening of the heart, an opening of the soul. This expansion is part of what we need to know about the world, and about how to lead our lives. This kind of beauty informs King Lear, and Anna Karenina, and To the Lighthouse, and Death in Venice. Beauty lies in the vision of the world created by these writers. Beauty lies in their deep understanding of the characters whose lives they chronicle, in their understanding of the great emotions, grief and joy and rage.

And through them we understand ourselves. While reading a great novel we think, yes, I recognize myself. Just as I recognized myself in Cinderella, or Jack and the Beanstalk, I recognize myself here. This person could be me. I myself might do just this: sin so abysmally, fail so utterly, grieve so profoundly. I might love so passionately, so selfishly, so wrongly. I might wound someone so horribly, I might dance so wildly, or so clumsily, drink so much, sleep so long, ride so fast. I might kiss, just like that. That could be me.

Entering into another’s heart is one of the most compelling ventures we can undertake, and fiction makes it possible. We use a great novel as a hinge on which to swing back and forth between the two worlds, fiction and reality. The novel allows us to understand how it is to take on the mantle of someone else’s mind, withhold judgment on someone else’s decision, understand someone else’s failure. All those things are part of what it means to be human. Not judgment but humility is the mark of the large soul; and the larger the soul, the greater the capacity for humility. Compassion is the way to understand the world.

Entering into another’s heart is one of the most compelling ventures we can undertake, and fiction makes it possible.

No matter what you do in your work, you will need to enter into someone else’s life. We humans aren’t meant to be solitary, we do badly alone: We sicken, we fail to thrive. Connection is essential. Great fiction offers us a way to connect with others of our tribe—I mean the human one—over the long span of thousands of years.

And great fiction lessens our sense of alienation from others. One source of war is a feeling of distance, which makes it possible to see other people as the enemy, the Other. Empathy diminishes this distance; empathy allows you to recognize the person in that strange face, strange skin, strange language, strange religion. Great fiction reminds you that this person is a human being, with needs like yours. So, yes: Great fiction is a force for peace.

Great fiction is spectacle, it wheels across the heavens like the Aurora Borealis. Thunderous and light-shot, it’s a pyrotechnical explosion, revealing things we’ve never imagined. It illuminates the night sky in sheets of rippling light; it illuminates the breadth and width of the world, as well as the small and intimate spaces within our hearts. It shocks us, in those bold and dazzling flashes, by revealing our own understanding of ourselves.

Does fiction matter?

Only if you want to be alive in the world. Only if you want to learn what it means to be human. Only if you care about what it’s like to slip inside someone else’s skin, to feel her life move within you, quick and vivid, like a trout in clear dark water.