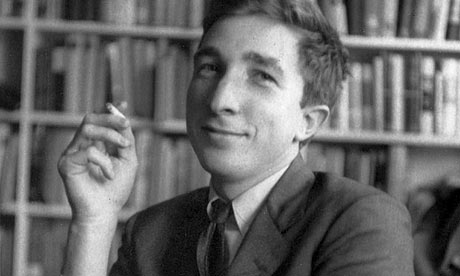

I was surprised in Elizabeth Hardwick’s writing class at Barnard when she told us that the mystery of Jay Gatsby was that he was Jewish. She stressed that, technically, The Great Gatsby is a first-person narrative, a work told by a survivor of the story, by a witness. Hardwick reminded us that Wuthering Heights is also a first-person work, a tale retold. The old woman settles us down by the fire—Heathcliff and Catherine, secrets, and the first-person of the witness. (In his latest novel, The Lost Child, Caryl Phillips, that Yorkshireman, expands on Heathcliff’s origins, gives black ancestry to Bronte’s dusky foundling.)

That Barnard class was decades ago, but I went on for many happy years listening to Hardwick talk about literature. She liked to think about St. Augustine, but hadn’t the same interest in, say, those passages in The Satyricon about Encolpius losing his boy love. The general point was enough: Confession, the voice under oath, or seeming to be—it had been around, even if the cultivated Roman world looked down on those genres that used the lowly, untrustworthy first person. Hardwick once dared me to remember at what point the first-person narrator of Kundera’s The Unbearable Lightness of Being disappears and the story takes over. You don’t notice his absence for a while, she insisted. She was talking about Kundera a few years after she had performed her own prestidigitations as the creator of an elusive, ambiguous first-person narrator in her masterwork of autobiographical fiction, Sleepless Nights.

Sleepless Nights came out in the reign of Donald Barthelme—loosely, the 1960s and 1970s, an era of radical interrogation of fiction as a literary form. Charles Johnson, Charles Wright, Alexis de Veaux, Wesley Brown, Henry Van Dyke, Toni Cade Bambara, Albert Murray, William Melvin Kelley, Gayl Jones, Toni Morrison, John Edgar Wideman, and, above all, Ishmael Reed—black writers were for me very much a part of this atmosphere of experiment, new departures. Fiction by black writers was escaping what, for many of them, had become the prison of realism.

When I was a student in the 1970s, some people seemed to think black writers excelled at autobiography, just from the sheer drama of the freedom struggle, but had somehow not achieved the same in fiction. It disturbed me to come across an essay in which Susan Sontag asserted that Camus, like Orwell and Baldwin, was a better essayist than a novelist. Good company, but it felt different to say that this writer is admired for his nonfiction, but not his fiction, when the writer in question was black. Given the prestige of the novel in American literary culture at the time, to say that blacks had an unfair edge in the genre of autobiography, but hadn’t mastered fiction, felt like a way of saying that in this field, blacks hadn’t proven themselves. Even Amiri Baraka had said, when he was still LeRoi Jones, that anyone who thought Jean Toomer’s Cane a masterpiece had never read Henry James.

Fiction by black writers was escaping what, for many of them, had become the prison of realism.

James Baldwin’s early autobiographical essays are radiant with the conviction that they are utterly necessary, that it had been an urgent matter that they got written. We associate his voice mostly with his swift, graceful essays, which have a completely different personality from his fictions. Sexuality is self-exploration in his novels and same-sex desire is a path toward liberation and higher consciousness. If Beale Street Could Talk sticks out as Baldwin’s straight novel. Other major writers whom I knew to be gay—Gore Vidal, Truman Capote—didn’t deal with men loving men as directly or often in their work. It was just Baldwin and Isherwood. Baldwin’s novels are also critical of U.S. society. I wanted to argue that his novels were handicapped by being what they were about and taking the political positions that they did, but I wondered deep down that, whether tightly structured or pretty formless, omniscient voice or in the first person, something about his fiction was not relaxed, wholly convinced of itself. His short stories didn’t have that anxiety.

I talked often with Hardwick about Richard Wright. She remembered the sensation that his novel, Native Son, caused when it was published in 1940. A black youth murders a white girl. The Communist defense attorney makes an impassioned plea for clemency, based on what the murderer had endured growing up black, that doomed someone American society had created. No amount of saying that Wright had been inspired by Dostoevsky, including a second murder we tend to forget, that the Communism was the equivalent of the Christianity at the end of Crime and Punishment, persuaded Hardwick that Wright had pulled off what some critics had denounced as his propagandistic conclusion. When the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, I realized that this criticism of the novel’s supposed major flaw had already faded away. Hardwick was very interested in an essay that Alfred Kazin wrote, taking back what he’d said about Native Son a half century before.

The New Critics were drawn to Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man when it was published in 1953, because it was free of the accusatory sociology white audiences had become accustomed to with black fiction in the realist tradition. A black novel was a Problem Novel. McCarthyism was everywhere and Time magazine praised Ellison for remaining in the United States while unpatriotic Wright complained about his native land from his residence in a country the U.S. had saved from the Nazis. America didn’t take kindly to rejection. After World War I, Henry James was criticized for having been an expatriate and the dust began to gather over his books. It was hard not to think that the New Criticism’s concentration on the text was, in part, a reaction to the persecutions, an intellectual accommodation of the political climate. Ellison’s young editor at Random House famously deleted the anti-colonial journals kept by the first-person narrator and in the scenes left behind, the 1943 Harlem riot became allegory.

In the 1980s, in another period of political reaction in America, Deconstruction once again closed off the text, dealing with it as unencumbered by the social world, unmoored from historical context. Ellison, who had suffered in the wilderness during the ascendancy of black militants in the 1960s, was vindicated. His duty was to his art, not to the revolution, he’d said to the angry young. Time had shown his art to be revolutionary, though the patriotism of his novel’s epilogue had to be forgiven. But Invisible Man was elevated as an urtext, the sublime, fantastic restatement of everything in the black autobiographical tradition. The blackness of blackness is most black.

Ellison had been the exception—until that experimental generation of black writers in the Vietnam War era made itself heard, in part because of his example. In Yellow Back Radio Broke-Down, Ishmael Reed’s Loop Garoo Kid defies the neo-social realist gang:

What’s your beef with me, Bo Shmo, what if I write circuses? No one says a novel has to be one thing. It can be anything it wants to be, a vaudeville show, the six o’clock news, the mumblings of wild men saddled by demons.

To move beyond realism was a way of saying that black novelists weren’t seeking anyone’s permission or approval and that the intention of their work had changed. They were not a Problem anymore. They were not there to explain racial things either. Toni Morrison said she never asked Joyce not to write about Catholic Dublin. Therefore, she could write about a black girl in Lorain, Ohio if she wanted and be as universal in her meanings as Joyce. Morrison is one of the least autobiographical writers in American literature.

Toni Morrison said she never asked Joyce not to write about Catholic Dublin. Therefore, she could write about a black girl in Lorain, Ohio if she wanted and be as universal in her meanings as Joyce.

There was a strain of black fiction that used folklore, from Zora Neale Hurston to Henry Dumas. But in Morrison’s fiction an African American writer appeared to have imported and adapted magic realism, which felt like a literary connection to Central and South America more than to West Africa. Early on, Morrison used to talk about the black novel as being aural. Degree of difficulty, that Modernist value, had taken root in black American literature. Ellison’s children were rather hard on Wright and the crusading realists who had worked alongside him. Bigger Thomas, Wright’s hapless murderer, gets mocked in the sophisticated satires of Percival Everett and Paul Beatty.

Hardwick liked for me to remind her that when I was her student she saw it as her moral duty to wipe out any notion I may have had about there being such a thing as a black novel, distinct from fiction by white people in its attitude to form or even in its ultimate purpose. After all, Morrison had written her doctoral dissertation on Woolf and Faulkner. Hemingway and Faulkner had more to do with the sound of black literature than anything or anyone else. Black writers were influenced by the same writers that their white counterparts were. But then I would think of a white writer who admitted to me that he’d never read Ellison, though he meant to. There are lots of things we don’t get to, for various reasons, but I suspected black writers knew more about white writers than white writers knew about black ones. Baldwin always said black people knew more about white people than white people did about us. But more so, it felt like they hadn’t heard Morrison’s news about universality and black subject matter; it felt like they still believed that books by blacks were about race finally. Lots of white people didn’t think race had any relevance to them. John Edgar Wideman said that the history of black literature was the story of a literature trying to jump free of its frame.

Black writers maybe wanted to cease being interpreters of black life or black history for the larger audience, but there was no getting away from the role, because the subject matter was supposedly foreign to that audience. However, the history of black American literature, or blacks in American literature, involved many, many years of trying to be heard, to present the black point of view, to overcome romanticism about race with realism. Once that had been accomplished, some black writers expressed the wish to have their burden lifted, that obligation to represent or to put forth. I wondered if seeing black subjects in fiction as automatically limiting stemmed from that postwar American hostility to the overt expression of ideas in a novel. No politics. It’s still with us in the depressing way MFA candidates are urged to show, not tell.

Yet Hardwick would stress that although non-fiction was also a form of imaginative prose, it was not fiction and therefore made a different contract with truth. Slaughterhouse-Five, ok? she said. Moreover, anything could be a subject, anything could be made from any subject. It was a question of language. Her encounter with Melville was so intense she had to write an intense book about him. In her old age, she read Dickens again and again just for the wildness of his language. She understood when I said that the tabloid realism of Native Son had begun to age somewhat, while the language of Wright’s autobiography, Black Boy, published five years after his best-selling novel, was always fresh in its power to convey the fear and insanity of the segregated South. She read for the thrill great prose gave her.

In her own writings, Hardwick had to find the right tone before anything else. Tone determined angle of attack; her judgments were in her tone. Her essays and late fiction were written with the same miraculous ear. She turned more and more to the first person. She could make it do many things. To watch her at work showed me that the writer and the narrator are not the same; there is an active self and a thinking self. Her voice is unapologetically literary, yet real. She was a woman who knew she was smart. Keep up. At the same time she was undermined by a womanly humility, by her love for the great works. It made her diffident about her own efforts. She was not prolific. Nothing she undertook was casual. Her voice is rare in its purity. She is a great soloist, but the first-person is also a mask.

The first person is a deflection, a conspirator

Hardwick admired the way the first person functions as a framing device in Philip Roth’s The Human Stain. Nathan Zuckerman lives. But she was fascinated by the first person as a smuggler of sorts, as a way to slip in on the reader new or radical ideas. When still in school I climbed the ladder up her shelves to fetch her much studied copy of Colette’s The Pure and the Impure, a work that blurs the line between memoir and fiction. Hardwick was interested in how little Colette actually says about herself. She just assumes her readers have heard of her. She uses her fame, her status, to protect the dignity of the actors, old roués, Don Juans, aristocratic lesbians, and gay boys with whom she talks throughout about their sexual conquests and desperate loves and true loves. The demimonde is not exploited. Colette is not an observer, but she is not a participant either. It’s good manners to let the guest speak. The first person is a deflection, a conspirator. Isherwood is present in Goodbye to Berlin, mostly as an impresario, getting his cast to perform. Rather than fake it, he let his women characters find him unacceptable as a boyfriend. I liked the code, the innocent, but homoerotic, the secrets he shared with me.

James Weldon Johnson’s The Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man, first published in 1912, is a work of fiction. The nameless narrator is a black man who has been passing for white most of his life. He is a widower, with two children. He relates his life as a black American, from his childhood to the moment as a young man when he decided to flee across the color line and live as a white man. Along the way, Johnson shows how what it means to be black changes from place to place, down South, up North, abroad. It is an awkward work, but Johnson, primarily a poet, is looking for a way to say some things that hadn’t been expressed in dramatic form before, things that it was nearly impossible to say at the time. He’s trying to give an indication of what it is like to be under sentence of racial discrimination. He has to use a gentleman narrator, a white man’s equal, to speak on the matter. White audiences accepted black autobiography, black testimony. There hadn’t been any black book as popular as Booker T. Washington’s Up from Slavery, published in 1901, even though in Washington’s day white historians of the Civil War refused to consider slave narratives as reliable documents on the grounds that they were not objective. Washington’s acceptance of Jim Crow was more reassuring to the white audience than stories of escape and resistance.

Dave Eggers’ What Is the What: The Autobiography of Valentino Achak Deng is an account of a Lost Boy’s flight across Sudan to the refugee camps of Ethiopia and then on to the immigrant’s insecure life in the U.S. He does not find solidarity with his black American brothers. The work brings us back to the slave stories that white editors wrote down incorrectly, edited in order to make them palatable. Part of the fame of Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass was that he wrote it himself. The same was true of the slave narrative of William Wells Brown. One reason Solomon Northup’s Twelve Years A Slave had been forgotten was that although Northup was literate, he did not write the story of his captivity himself. His is an as-told-to book. What Is the What is not an as-told-to book, though Eggers talked to Deng extensively, to say the least. But the white amanuensis becomes the black voice. It is a riveting novel and you can feel the relief in his being free to do what is necessary when needed, including telling in parallel Deng’s African and American experiences.

The third person voice can be about many things and get in many heads. By comparison, the first person is a strict organizing principle. It tends to be only about the narrator and his or her relation to the world, or to a world. Its authority rests on how well it can persuade, seduce. Then, too, the job of the first person is to remember. I liked—and like still—how the best fiction turns out to contain the historical truth as well. Don’t we now read The Great Gatsby in order to learn something about the customs of the Jazz Age? Hardwick disagreed. We read The Great Gatsby because it is a perfect work, she said. To read is not therapy, she said. We read in order to learn, yes, but we read short stories and novels for the sheer pleasure of them, to have the experience of them as part of our lives. Similarly, we write in order to inform in some way, but we write fiction as a way of honoring the work we care for. There are many kinds of writing, and many reasons for all of it, but the fiction we care about is an art form, she said. I should recognize that black life made for an interesting and real subject, but the art was in the telling. Remember, it has no reward outside of itself, she said. Then she was off on to Lolita or Moncrieff’s translation of Proust….