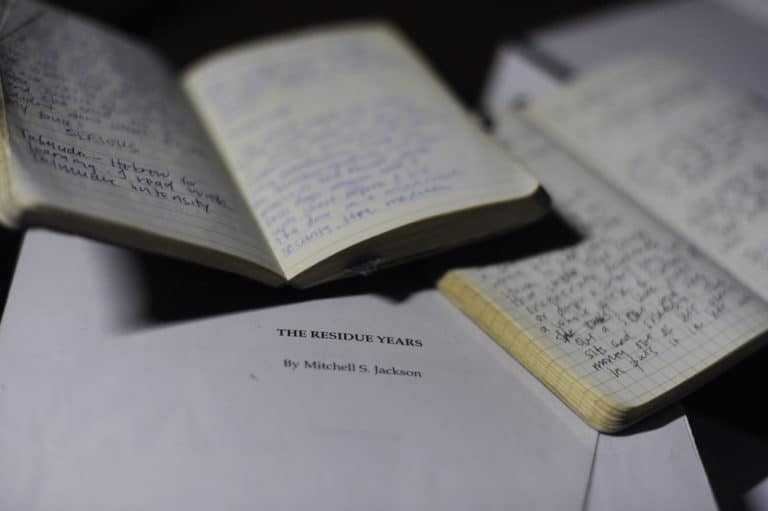

There used to be a very strong tradition of novelists who also wrote journalism, this seems to be less the trend now, however, I still happen to be one of those novelists and my journalism, or nonfiction, certainly influences my fiction. The antecedents of much of my fiction reside in the essays and dispatches that I write. These are, in many ways, my first notes on a novel. My latest book Dark at the Crossing takes place in southern Turkey and Syria and is the story of a failed revolution told through the prism of a failed marriage. Although it is a work of invention, the people I’ve met during my travels in the region have informed the characters in the book. Below are a few articles, which I view as early sketches.

The Fourth War: My Lunch with a Jihadi

During the winter of 2013, I was living in a house with a number of journalists, researchers and aid workers in Gaziantep, or Antep as the locals call it, a city in southern Turkey where much of Dark at the Crossing takes place. One evening, my friend Abed, a Damascene Syrian who had been a democratic activist in the revolution’s early days but who had since fled his home and now worked for a local research firm, wandered into the kitchen after a day spent at Akçakale refugee camp which straddles the Turkish-Syrian border. As we rummaged around the cupboards preparing a simple dinner, he said in the formal English that he speaks with a slight British accent, “Elliot, I’ve met someone today who I think you should meet.” “Okay,” I answered, “Who?” Abed continued, “Well, his name is Abu Hassar and he used to fight for al-Qaeda in Iraq, but I think you guys would really get along.”

The story that follows is that meeting: two veterans of the Iraq War, albeit from different sides, along with a former Syrian democratic activist, sitting across from one another for lunch. The exchange that followed—between myself, Abed, and Abu Hassar—informed much of the ideological counterpoint between Amir, a central character in the novel, and a representative of the Islamic State named Athid who figures prominently in the book’s climax.

Living in Istanbul and Gaziantep, I’ve continually met expatriates who spent years in Iraq and Afghanistan. What has brought so many back to the Middle East, and now to Syria? The fate of kidnapped journalist and Marine veteran Austin Tice haunts those who continue to flirt with conflict. When I met Vince Perritano, a former Marine who participated in the 2011 democratic protests in Cairo, he told me his reason for living in the region was, “to be close to it.” But what is it? For so many, it is an experience so large that we shrink to insignificance in its presence. Vince, who has battled with PTSD and suicide, lingers in Istanbul eking out a living on his VA benefits and the wages he earns teaching English in a school funded by the Islamic Gülenist group.

Back in the States, on an early morning run with another friend, a special operations officer who has deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan continually since 2003, we talk the wars. He then leans over to me and says, “You know, Ack, the melancholy of it all is that we grew up there.” For Haris Abadi, the novel’s protagonist, his experiences as an interpreter in Iraq have left him rudderless. Wanting a new direction in his life, he leaves the United States, “to sacrifice himself for a free Syria, a cause he knew to be right, [which] was the opposite of all he had done before, fighting alongside the Americans in a cause he felt to be wrong.” The return to war as a redemptive and at times self-destructive act was a theme that kept coming up among those I met in my travels. I first wrestled with it in this article and it is a central theme within the novel.

Watching ISIS Flourish Where We Once Fought

When the Islamic State swept back into Iraq in the first part of 2014 by seizing Mosul, Fallujah, Ramadi, and several other cities, I turned to my Syrian friend Abed to try to make sense of the strong reemergence. Having gotten to know Abed and other Syrian activists over the years, what had become clear to me was that although their methods were very different, they had embarked on an ill-fated democracy spreading mission in the region just as the American military had the decade before, and when their revolution failed they were left questioning the ideological assumptions they had begun with.

This piece of journalism, written immediately after the Islamic State’s major advance into Iraq in 2014, reflects on the counterintuitive bond that exists between American war veterans and Arab democratic activists, two groups who both applied failed methods to bring democratic change to the region, and who were both undercut by religious fundamentalism. This linkage between the American and Arab experiences in Syria and Iraq was something I wanted to explore in the novel through its protagonist, Haris Abadi, a naturalized American from Iraq, who served as an interpreter during the war. However, my interest in the commonality between American war veterans and Syrian democratic activists was only beginning to coalesce as I wrote this article.

The city of Gaziantep, or Antep, plays a significant role in the novel. I wanted to capture the mood of this Turkish backwater, which has become a crossroads for so many in Syria’s diaspora as well as a boomtown for internationals who have come to the region for both charity and profit. This piece focuses on two poets, Aref and Ammar, who have tried to recreate a Syrian cultural life in this Turkish city. I met Aref and Ammar through Abed, who comes from a long line of poets, and they shared their work with me over coffees at Sanko Park, a shopping mall whose ice skating rink—a surreal fixture only fifty odd kilometers from Aleppo—also figures prominently in the novel.

Although both Aref and Ammar had escaped the war and managed to craft a reasonable life across the border as refugees, they wrestled with what I can only identify as survivor’s guilt, something which plagues the relationship between Amir and his wife Daphne in the novel, a couple who lost their daughter in a tragic incident. When discussing the freedom they had now found to write poems critical of Bashar al-Assad’s regime, Aref told me, “From here, I can write anything I want. We Syrian poets are free.” Then he paused for a moment, as if thinking about his last comment. “The only problem is without Syria, there is no Syrian poetry.”

❦❦❦