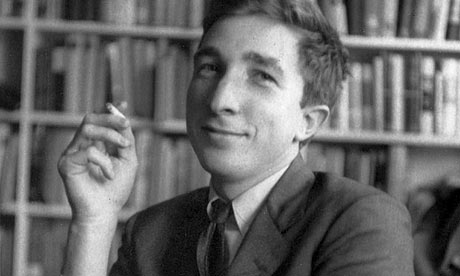

When I first read Robert Stone’s work I was struck by the beauty of the sentences. That’s the way a writer reads, listening to cadence and rhythm and beauty, and that’s what first draws your respect and attention. Also the perfect economy of his prose: “Father Egan left off writing, rose from his chair and made his way – a little unsteadily – to the bottle of Flor de Cana which he had placed across the room from his desk.”(From A Flag for Sunrise).

The very first word here reveals the dark and monumental presence of the Catholic Church. With the next phrase we see that Egan cannot complete his task, struggles with alcoholism and makes a pathetic attempt to combat it. We know everything we need to know in the first sentence about the core of this man – his hopes, his conflicted life, his failures.

So Stone scores on economy and then begins with very high stakes: the Catholic Church, alcoholism and the struggle for a man’s soul.

And really, Stone never looks back from those beginnings, which characterise most of his books. The stakes are always high, the struggle always concerns the essential struggle of the soul, the fear of that holy interior failure, and the sense of fearful awareness of the inadequacy of human attempts to succeed at something so important.

American novelists don’t usually write about religion, but in many ways Stone wrote about it always. He was always aware of that deep terrifying battle for the soul, and though the Catholic Church was often presented as a source of darkness and not light, it was usually the Church who drove a powerful tide through his work. His work presumes our understanding of Catholicism’s ancient and powerful magnetism, its fetishistic and aesthetic characteristics, its presence in literature, architecture, music and art. He ranges widely among that totemic landscape, though his own landscape is deeply contemporary, often sardonic and never reverential.

The first time I ever had a meal with Robert Stone was at a restaurant on the beach in Key West. A group of us were sitting around a table, talking and laughing. It was late evening, and we were having dinner in the fading roseate light of the famous Key West sunset. The restaurant was right on the beach, and the tables were separated from the rest of the public space by a high wooden fence set at right angles to the water. We sat in the shelter of the fence, at a wooden picnic table. We were having dinner, drinking wine and telling stories as writers like to do, laughing and giving the punch lines and watching each others’ faces in the dimming light.

What happened was like something in a combat zone. Suddenly we were all confused: suddenly something had happened but no one knew what. Something had turned light and dangerous and fast but no one for a few long moments knew that something had landed out of the sky and exploded on our table. Splinters of glass flew out in a glittering circle, though, miraculously, no one was hurt.

We stared at each other for a few stunned seconds, the adrenaline starting to thud, the pulse starting to rise. A beer bottle lay shattered on the table. Bob stood and began to run through the sand, around the end of the wooden fence. He ran at speed, with an oddly low stance, not exactly crouching, but keeping his center of gravity low, as though he were ready for something.

What he found was a couple of high school boys, of course, a little drunk, a little stupid, who’d thought it would be hilarious to send that empty bottle spinning up into the evening sky and then down, to shatter onto an unseen target. When Bob reached them what he had to say was not friendly. He raised his voice. The rest of us waited, shaken, for his return. He came back, still running, still in that curious low stance, but his face now turned up, open. He looked exhilarated, as though he’d just taken a swim through the ice floes.

No one else from the table had jumped up and run to confront our hidden attackers; that wasn’t the only way to deal with the situation.

Bob’s response was immediate and instinctive, defined by equal parts of clarity and ferocity. No anxious hesitation, no moral uncertainty, no fear. Here was a clear and present danger; here was a fierce and practical response.

Which was how Robert Stone wrote. He took on the challenges of the deepest, most shameful failures of the human soul, the very darkest parts of man’s desiring, the barest and most arid places in the heart’s struggle to survive. Irony was present, but it wasn’t the driving force. Irony is distancing and diminishing, and Stone was in deadly earnest. Like a Catholic priest, he understood the real risks of being alive, the terror of owning a soul. Those were his subjects, just those risks, just that terror. He went straight after them.