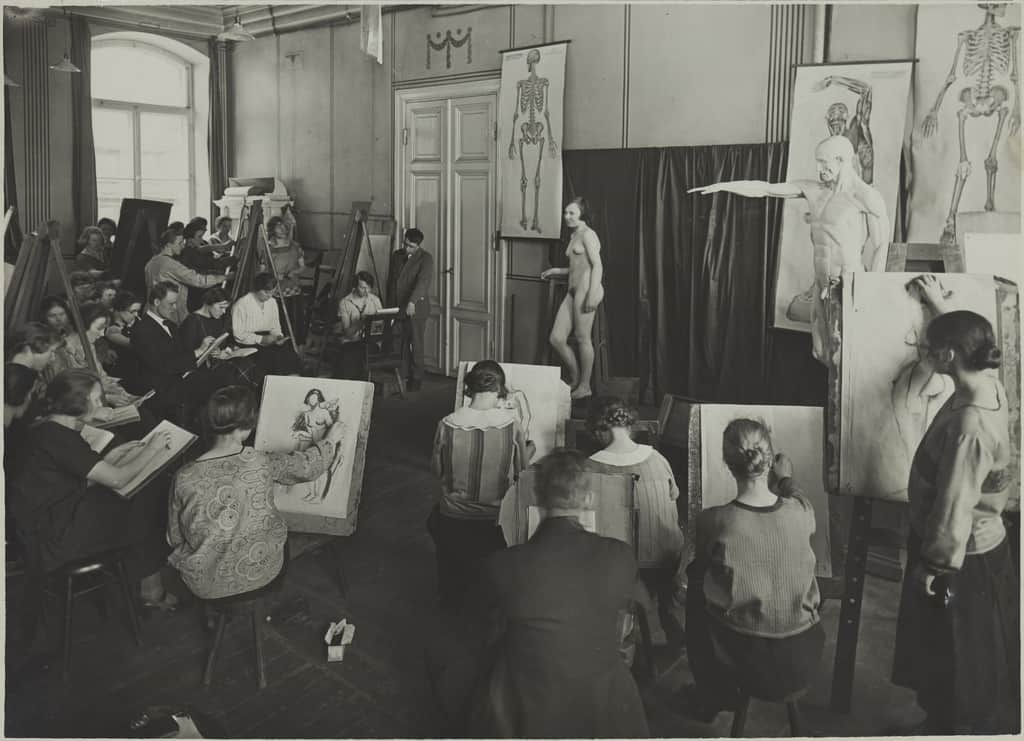

I was sixteen when I saw my first naked man. I’d signed up for a figure drawing class at The Arts Students League and, rather naively, hadn’t realized the models were nude. That was the whole point—you were supposed to learn the structure of the human form, free of loose folds of cloth and other visual impediments.

I lifted my eyes, raised a trembling hand to my newsprint pad, and sketched away. I did not budge from my stool.

As the weeks went on, I still stayed fixed in that same seat: just to the left of the model (whose private parts were tucked neatly away from view). I always drew from that same three-quarters perspective. I’d made some improvement from my earlier sketches. I was content.

Maybe even complacent. In one class, my instructor looked over my shoulder, surveying my work. He told me to get up and walk around the model. “The only way you’ll understand the structure of the body is if you go look at it from all angles,” he said.

“But I’m drawing from this angle.” My reluctance to move wasn’t just due to my apprehension in seeing the model’s whole naked body; it was that I couldn’t understand how looking at the model from other angles would help me draw from this particular one. It felt like being untruthful to my current perspective, and I said as much: “Isn’t that, like, cheating?”

The instructor pointed to my sketchpad: the model standing with an arm wrapped behind his torso. “How are you supposed to capture the foreshortening here”—he pointed to the lopsided arm—“if you can’t see what’s going on behind it?”

From where I sat I could see the model’s arm was hooked behind him, but it was only when I rose from my seat and walked around him that I realized his hand was resting flat in the small of his back, which explained the torquing of the forearm. I saw other things, too. The tension in his hamstrings corresponding to the sinews running down his quads. I saw the folds of skin between his shoulder blades—which explained his puffed-out chest. Everything happening behind the scenes was informing what I had viewed from that first angle. From where I had been sitting, I realized I’d been seeing only half the picture.

In an interview about Motherless Brooklyn, Jonathan Lethem revealed that as an exercise, he wrote the whole novel—told from the first-person perspective of a man with Tourette’s—from other points of view. He tried out the third person. Other characters’ perspectives. The interviewee didn’t believe him: surely not thewhole novel! Lethem insisted he’d rewritten the whole thing knowing full well he would eventually return to the first-person perspective. I immediately thought of those art lessons, and how reluctant at first I’d been to get up from my seat and view the subject of my work from other angles.

I’d heard Lethem’s interview at a time when I was struggling with my own novel manuscript—also a first person narrative. One scene in particular, where my protagonist first arrives in Brooklyn and goes on an interview, would not click no matter how many times I rewrote it.

I decided to take the Jonathan Lethem-lite approach: I jumped into the heads of the other characters in the scene and rewrote it from each of their points of view. I wrote from Jane’s boss’ perspective, and found myself surprised when she—a professor of Women’s Studies—launched literary allusions that went straight over Jane’s head. I wrote from the husband’s perspective, recording each sniping comment and sigh of exasperation he made in his wife’s wake. I even wrote from the perspective of their little girl sitting by the window as she watched the three adults and their awkward interactions.

When I returned to my protagonist’s first-person perspective, I found myself writing a much richer scene: I now knew what the bit players were doing and saying, how much of that Jane was able to perceive (versus what the reader was able to pick up on), and how everyone worked in concert (or not) with each other. I was able to heighten subtler tensions that I hadn’t known existed before. In looking at things from the other characters’ perspectives, I got to know Jane more.

Sometimes troubleshooting might simply be a matter of getting up from your seat—or your comfort zone—and trying anew from a different angle. In so doing, you gain a more holistic understanding of your subject: the nude model, your protagonist. Perhaps this is why our favorite characters in literature are often outsiders. Freed from the constraints of a fixed perspective, they move fluidly on the peripheries of fictional worlds, offering insight from the outside looking in. Never do they risk being so buried amidst the trees that they fail to gain any perspective on them.