As someone who writes both journalism and fiction, I have often struggled with how to balance research and imagination. The journalist half of me insists on being as accurate as possible; the novelist half of me wants the freedom to invent.

Yet both halves know that if I am going to set a novel in a real place, in a real time, I must get all the details right. I should not put a wall around Washington Square, start the Iraq War in 2005, or claim that maple trees bear acorns. This matters because it has to do with keeping faith with your readers. If you get something verifiable wrong, why should they believe you when you really are making things up? Research, factual accuracy, lays the base for plausible fiction, for it actually enables suspension of disbelief in readers by building their trust.

This hit home for me long ago, when I read a novel set in Berkeley, California, a city I know well. On the U.C. Berkeley campus is a well-known landmark called Sather Gate, which is merely two ornate metal pillars, not a gate at all. But in this novel, the author swung the gate closed and even locked it.

I almost threw the book away. I felt the author had violated her contract with me, her reader. She had closed the nonexistent gate either because she was too lazy to check if it could be closed, or because—and this was worse—she chose to ignore reality for the sake of her plot. And that felt like a cheat.

I have heard fiction writers speak cavalierly of facts. “Who cares, make it up, it’s fiction!” But having been traumatized by that gate, I profoundly disagree. If a writer wants to create a plausible world that draws in readers, makes them laugh and cry, believe and feel—if the writer wants the readers’ respect—that writer owes them as much accuracy as possible.

Yet research has its pitfalls, especially for those who’ve learned to write as journalists. Research needs to be kept in check, like a hungry dog on a leash, lest it gobble your imagination and your story as well.

One pitfall is to concoct a story to fit the facts. That is, instead of letting the story evolve out of your characters, you twist your characters and plot into illustrating your research. This leads to characters doing and saying things they never would, which turns them into puppets and wrecks their credibility, and probably that of your story, too.

Another common mistake is to fall so in love with your research that you stick in facts all over the place, thus clogging the narrative and making you sound like a show-off: “She donned her necklace, made of a rare blue amethyst discovered by Richard Burton in the mines of Eastern Peru, and went down to dinner.” This leads to fiction filled with factoids but without a believable character in sight.

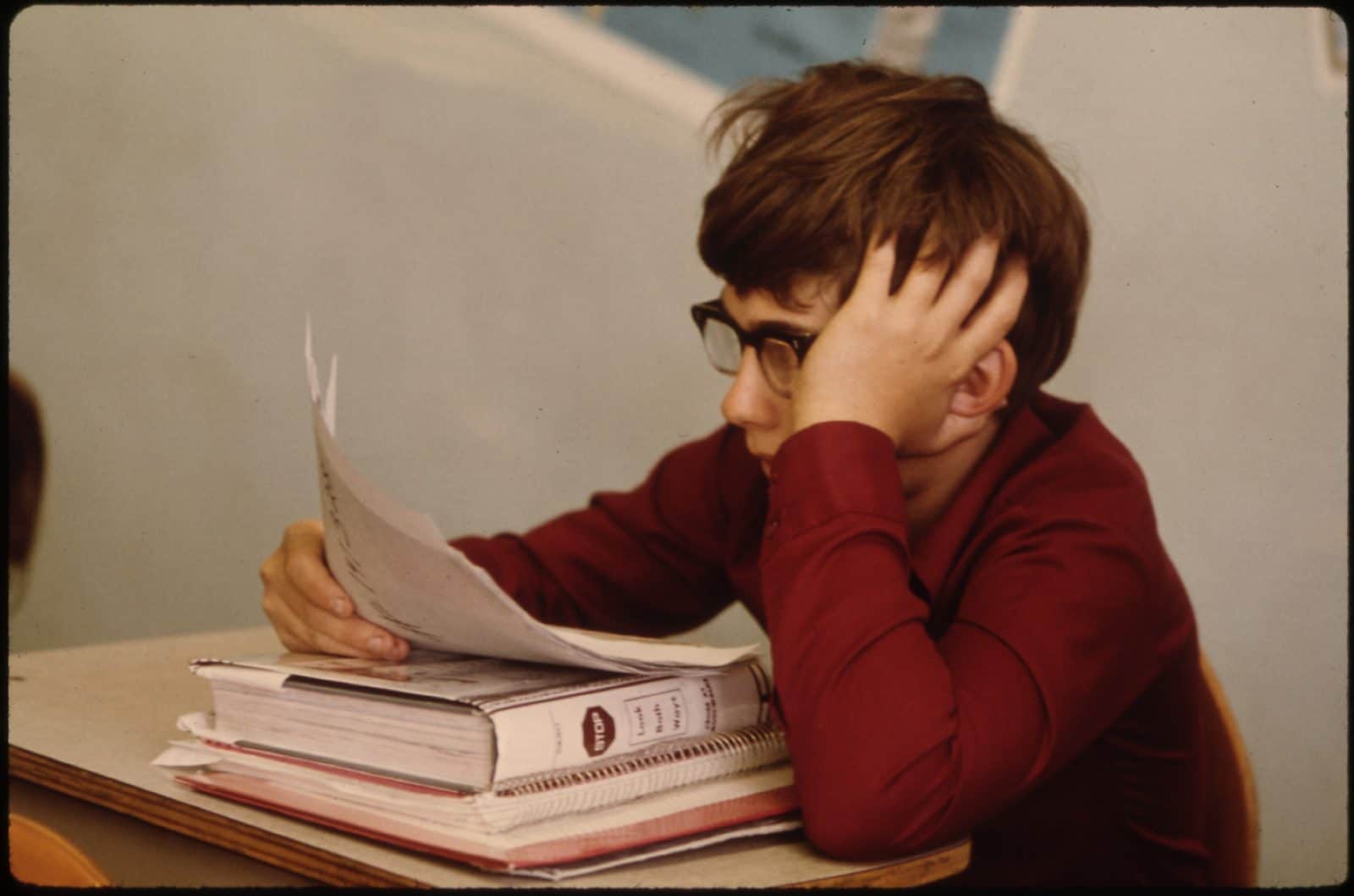

I faced this last temptation myself—wanting to show off my research—when I crossed over from writing my nonfiction book about women soldiers in the Iraq War, The Lonely Soldier, to my novel about the same subject, Sand Queen. Soldiers speak in a lot of jargon and acronyms, many of which are funny. In nonfiction one can explain these easily, but when I was writing in the first person voice of a soldier, it wasn’t natural to have her explain things she says as matter of course. So I had to let some of my favorite gems go. For example, soldiers who need glasses are issued BCGs, or Basic Combat Glasses, but they are so ugly that soldiers call them Birth Control Glasses, the idea being that they make you so hideous no one will sleep with you. One of my main characters in Sand Queen, Jimmy, wears BCGs, but I just couldn’t fit in that explanation naturally.

As necessary as research—controlled research—is for keeping faith with the reader, perhaps its most important use is mainly behind the scenes, not on the page. Thorough research instills in the writer enough knowledge to give her real confidence in her material—the kind of confidence that releases her from a need to show off or twist her plots, and frees her to finally sit down and write.