I met my best friend, Mat, in graduate school. We were in the same writing program, shared similar backgrounds and senses of humor and that’s really all a good friendship takes to get going. We were in the same lectures, shared a workshop once, and spent much of our outside time going over the books we were reading for school, the feedback we’d been getting on our fiction, and our ambitions for our careers after we graduated. We both enjoyed the great luck of publishing first books soon after leaving school. He wrote a novel and I had a collection of stories. Then he published a second novel and I published my first. We both felt like we were on the right path.

Soon after he published that second novel Mat was offered the chance to write a comic book. For guys like us—who’d been comic heads since childhood—this counted as a high honor. He said yes and I asked for details about the process almost every day. His editor said he’d have to write a script for the comic. This meant writing out exactly what was said, what was seen, and what was happening on every panel of every page in the issue. After he’d done all this the artist would take that script and turn the stage directions into illustrations. (Panel one: Superman punches Batman. Panel two: Batman grimaces. And so on.)

A few days later he called me up. He sounded dazed. He’d been writing his script and quickly noticed a pattern. In the first panel his characters sat around a living room talking. Then in the next panel they were standing on the sidewalk talking. Then in the third panel—big dramatic turn!—the characters were sitting again, in a coffee shop this time, and they were talking some more. Was he supposed to just go on like this for twenty-two pages? (The length of an average issue of a comic.) If there were six panels to a page that would mean one hundred and thirty panels of people sitting around talking. Who could ever endure such a thing?

But then we both realized that a scripted version of all our published fiction—novels and short stories—might look exactly like that. Scene after scene of people sitting around yapping. Hard to create much drama from people doing the exact same thing on every page.

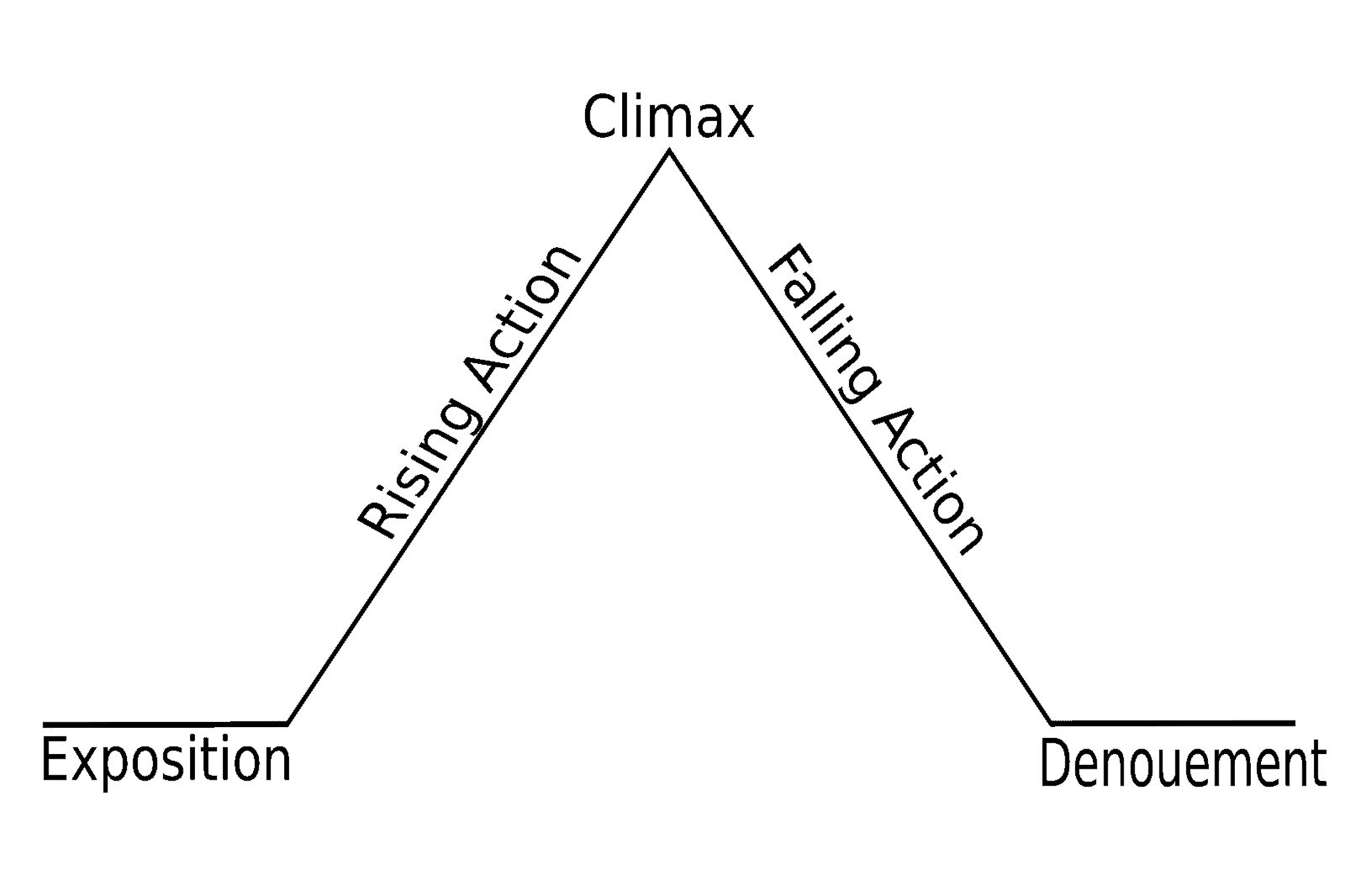

The problem, we realized, wasn’t necessarily the lack of big action scenes. The problem was that we hadn’t even been able to recognize the narrative structures, or lack of narrative structures, in our work. We’d been taught so much in our graduate program—and became substantially better writers because of it—but there’s a kind of blind spot, an essential flaw, in the workshop method that contributed to our problem. In class we’d discussed each submission seriously, were schooled about our characterizations, our use of language, our voices, our ideas. But we rarely, if ever, discussed the structures of our stories. Never examined the reasons why we’d told this story in this order. And I think this is because the structure of the piece is one thing that’s often taken for granted in a workshop.

There’s an unspoken assumption that the story, as it was handed in, is in the “right” order. As a group we might criticize the characters, the setting, tear apart imprecise language and clichés. We might suggest cutting lines or scenes, maybe even characters but I can’t remember anyone rearranging our narratives. Could these scenes be repositioned to greater effect? Was there a clear beginning, middle, and end hiding somewhere in this flashback-heavy story? Or was I using flashbacks to obscure the fact that there was actually very little narrative here at all? In workshops we take it for granted that an author might need to rethink so many components of his or her story but we rarely seem to assume the same of the structure of each piece. And because we don’t talk about it the issue becomes harder and harder to recognize let alone rectify. It might take your best friend finding work in a different genre to expose a blind spot you’re suffering in your own.