Founded in 1821 as The Mercantile Library of New York, eighty-two years before the New York Public Library began, The Center for Fiction has played a vital role in the literary life of New York City for over 200 years. Read about our organization’s history, and its transformation into a home for readers and writers in Brooklyn, below.

The Nineteenth Century

The Nineteenth Century

When the Mercantile Library of New York opened its doors at 49 Fulton Street in February 1821, James Monroe had just begun his second term as president of the United States. New York City had either 123,000 or 152,000 inhabitants, depending on which census you believe, and the population of the entire United States numbered only 9.6 million. It was a year that marked the death of Napoleon, the coronation of George IV, and the entry of Missouri into the union as a slave state. American writer James Fenimore Cooper published The Spy while in England readers pored over Thomas de Quincey’s new book, Confessions of an Opium Eater. Keats died and Baudelaire was born.

On the streets of lower Manhattan, a sense of opportunity and the possibility for both financial and social advancement reigned. As Theodore Roosevelt wrote in New York, his short history of the city, “The distinguishing features of the life of the city between 1820 and 1860 were its steady and rapid growth in population, the introduction of an absolutely democratic system of government, the immense migration from abroad . . . and the great material prosperity, together with the vast fortunes made by many of the business men, usually of obscure and humble ancestry.”

Young men in the mercantile trade were no doubt inspired by the successes of men like John Jacob Astor, who had arrived in New York City penniless, the fourth son of a German butcher, and by 1820, had risen to be one of the richest men in America. The American dream seemed there for the taking for these young clerks who saw how DeWitt Clinton’s opening of the Erie Canal and the advent of the steamship had made New York a thriving commercial center. They eagerly responded to a notice placed by a Mr. William Wood in the Daily Advertiser announcing a meeting to be held at the Tontine Coffee House on November 9, 1820, “to consider the propriety of establishing a Library and Reading Room for merchant’s clerks.” Wood was a native of Boston who had risen from simple beginnings to become a merchant with a thriving British-American trade. He had a great interest in young people and a desire to create future business leaders out of young men just beginning their careers. He was devoted to reading and to the education of mercantile tradesmen and established libraries aboard ships.

Wood was also one of the first Americans to expand upon and put to use Benjamin Franklin’s recommendations for the creation of lending libraries. Throughout his life, he spent a great deal of time and money in the establishment of such institutions. He founded a library for clerks in Liverpool, no doubt inspired by the grander Liverpool Athenaeum, and after his return to America, established in Boston the first institution of the kind in this country, a few months before the beginning of the Mercantile Library in New York. His plans for lending libraries were adopted in Philadelphia, Albany, New Orleans, and many other places, and in 1823 he founded The Apprentices Library Association of the Village of Brooklyn, afterward known as the Brooklyn Institute and Youths Free library.

Wood’s methods were somewhat unorthodox, and an amusing glimpse is given in Henry Stiles’ A History of the City of Brooklyn: “Wood called at the office of a Brooklyn newspaper one day to talk over his project of an Apprentices Library, and found the editor, Colonel Spooner, delighted with the idea. ‘Well,’ said Mr. Wood, ‘Let’s begin at once,’ and with that he proceeded to select from the editor’s shelves all the volumes that were suitable for his purpose and to pile them up in a corner. It was several years before the society was rich enough to buy any books. All was done at first by begging, and it is related that the officers, at Wood’s urging, used to go around from house to house with a wheelbarrow to collect donations.”

Nearly two hundred and fifty young men responded to Mr. Wood’s notice in the Daily Advertiser and attended the meeting at the Tontine Coffee House. This large and enthusiastic turnout clearly indicated that there was a need for a place where enterprising young men of the day could educate themselves. With Mr. C. C. Cambrelen acting as chairman of the meeting, Wood talked with the young men and filled a small group of them with enthusiasm for the scheme. A second meeting was held on the 27th of the same month, and a constitution was adopted and the first officers were chosen: Lucius Bull, President; George S. Robbins, Vice-President; and Allen Robbins, Secretary. Mr. Wood was elected a director.

The board lost no time in getting to work. Wood talked with a number of established merchants, convincing them that by investing a few hundred dollars, they could help to establish an institution that would keep their employees “away from the rum-shop and the billiard-room.” Other Board members solicited donations of books or bought volumes themselves. Within the month, the group had established the constitution for the Mercantile Library of New York, stating, “We the subscribers, Merchants Clerks of the City of New York, being desirous to adopt the most efficient means to facilitate mutual intercourse; to extend our information upon mercantile and other subjects of general utility; promote a spirit of useful inquiry; and qualify ourselves to discharge with dignity the duties of our profession and the social affairs of life, have associated ourselves for the purpose of establishing a Library and Reading Room, to be appropriated to the use of young men in mercantile pursuits.” Only merchant clerks were permitted to hold office and to vote in the Association.

On February 12, 1821, the library opened in a large room on an upper floor of 49 Fulton Street under the guidance of its first librarian, John Thompson. Dues were two dollars a year and there was a one-time initiation fee of one dollar. Thompson received $150 a year to oversee a library of 700 volumes, which was open to its members during the early evening hours. By the end of that year, the library association had grown to nearly 200 members and the library contained over 1,000 volumes.

Though the mission of the library was to educate young men for success in the mercantile trade, from the very beginning fiction was a popular part of the collection. The second annual report noted, “As the cultivation of a correct taste in reading was one of the first objects proposed in the establishment of the Library, it is gratifying to state that this has been in great measure effected. A few of the best imaginative works are permitted, and these were at first the oftenest called for by members, but the voice of wisdom has made itself heard, and many who were wont to devour pages of romance alone have become readers of history and lovers of science; and many we hope have there received the first impulse to faculties which would otherwise have laid dormant and neglected.”

In fact, the members’ love of fiction continued to defeat these laudable goals. As the Annual Report of 1825 recounted, the circulation of “works of fancy” continued to exceed that of all other categories. By 1836, after members staged a small demonstration the Board of Directors surrendered completely to the desire to read more fiction and the annual report of that year states: “The addition of works of fiction offers an inducement to seek for the acquirement of knowledge in the alluring fields of romance and the imagination.” What had early been seen as a diversion was now considered “a path to knowledge.”

Despite the core of young merchants’ clerks who were devoted members, in its first three years of its existence, the Library struggled to stay alive. Circumstances seemed to conspire against it in 1822 as the last of the major yellow fever epidemics in the Northeast struck. In that year’s annual report, Lucius Bull, the president of the Mercantile Library Association wrote, “In common with all classes, we, as a body, have suffered by its desolating influence; and the deserted apartments of our Institution have borne testimony to the prevalence of danger and death.” By December 1823, membership had dropped from a high of 308 in early 1822 to 189. Only a $250 gift from the Chamber of Commerce kept the doors from closing permanently.

Buoyed by this support, Lucius Bull called for prominent merchants in lower Manhattan to become involved. Members of the Board agreed to divide “the principal streets for business into suitable districts, to wait on the merchants at their counting rooms, in each district, for the purpose of making the advantages of this institution known to their fellow clerks [and] at the same time to solicit the influence of the merchants in aid to our endeavors and to accompany their good wishes for our prosperity with such donations in books or cash as they might be disposed to give.” In other words, the Library began its first organized fundraising campaign in 1826.

Through the efforts of these Board members, led by the indefatigable Mr. Wood, the prospects brightened to the extent that the officers hired a suite of rooms in the Harpers building on Cliff Street and started the reading room, which has continued to be an important part of the institution in all its successive homes. By 1828 the membership and collection had grown to such an extent that the need for the Mercantile Library to have a building of its own was apparent. As the president, Robert Brown, pointed out, “there are disadvantages attending our present location, which have served to deter some from becoming members. The library is too much retired from public notice. There are, doubtless, very many, who, if the situation were more public, would become attached to the association. We need a situation which should be central, spacious, and commanding, which should bring us more constantly before the eyes of the public, and at the same time, be better adapted for the convenience of the members.”

The collection now numbered 4,400 volumes and there were nearly 1,200 members. Merchants who had initially been skeptical about the library’s chances of success had been converted. The mayor of the City of New York, Philip Hone, was an enthusiastic supporter and a well-publicized and well-attended series of lectures at the library had heightened its profile. All conditions were favorable for a move to a new location.

It was at this point that the relationship between the merchants’ clerks who ran the library and the merchants who supported it became formalized. In 1828, a group of leading merchants and established businessmen that included John Jacob Astor had formed a group that they called the Clinton Hall Association, in honor of DeWitt Clinton, who was governor of New York at the time. Clinton had overseen the completion of the Erie Canal and encouraged the steamship trade that emanated from the port of New York northward and was therefore much beloved by merchants of the city, who felt they owed their financial success in part to him. The Clinton Hall Association was created in order to support cultural institutions in New York City; before entering into an agreement with the Mercantile Library, it first approached the New York Society Library, but was rebuffed. It was only after this rebuff that the Mercantile Library was considered. To the group, the idea of housing a Mercantile Library in a building called Clinton Hall began to seem especially appropriate.

The merchants agreed to become a permanent holding company with shares to be held only by themselves and their descendants. The idea was to have an organization of older, successful businessmen responsible for the financial wellbeing of the library and entirely separate from the association of clerks who ran its operations. The first shareholder to contribute to the fund to build the new library was John Jacob Astor, who purchased 10 shares in the association at $100 each. He was joined by other merchants, who together contributed $34,000. With these funds in hand, they decided to erect a building that would include more rooms than the library needed, and to rent out the additional rooms. The money received would be used first to clear any debt on the building and then to purchase books. The Mercantile Library Association members agreed in turn to pay, out of membership fees, any taxes which might be imposed, to keep the rooms in good repair, and to contribute an equitable portion of maintenance expenses. Land was purchased at Beekman and Nassau Streets.

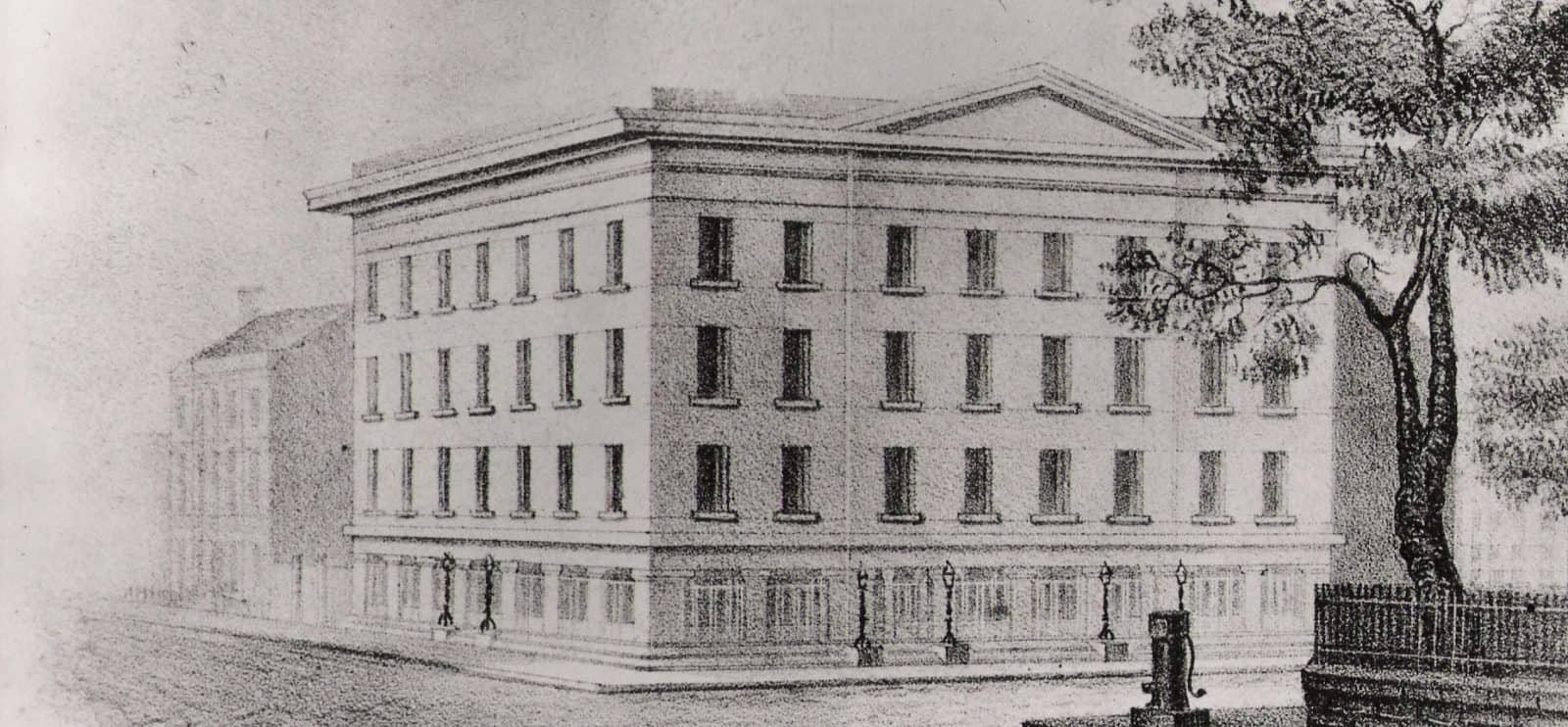

When the new library building called Clinton Hall opened in November 1830, the library had 1,200 members and over 6,000 volumes and included not only a Reading Room, offices, stack space, and the rental rooms, but also ample space for writers to work. Edgar Allan Poe was one of the first writers to occupy one of these spaces. The manuscript he was working on was probably Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque, published in 1839 by Lea and Blanchard, but he may also have been working on The Conchologist’s First Book, an early and useful resource on sea animals with shells that has been the subject of some controversy. (It appears that Poe borrowed extensively from Thomas Wyatt’s Manual of Conchology.)

Over the next few years, in spite of some occasional financial difficulties and minor disagreements between the Clinton Hall Association and the Mercantile Library Association, the Library continued to thrive. Its debt on the building was very soon retired and the collection increased exponentially. In 1839 classes in chemistry, French, Spanish, and German as well as “The Art of Drawing” began. By 1850 lectures at the Mercantile Library were important events on New York’s cultural calendar, drawing standing-room-only crowds. That year, lectures were delivered by Ralph Waldo Emerson, Richard H. Dana and actress Fanny Kemble, who read from Shakespeare as part of a national tour that also included venues in Massachusetts, Michigan, Chicago, and Washington, DC. In 1852, Oliver Wendell Holmes was a featured speaker; in 1853, William Makepeace Thackeray came from England to deliver a talk entitled “English Humorous Writing in the Reign of Queen Anne.”

As New York City grew and moved uptown, so did the Mercantile Library. In 1854, the Clinton Hall Association purchased the Opera House at Astor Place and Lafayette Street. In its new home, membership was no longer limited to clerks, but was opened to all “people of good character,” including women. Columbia University and University of the City of New York both began to provide “scholarship memberships” to the library, and an ambitious schedule of classes and lectures that had been established at the first Clinton Hall downtown continued. Even today, as one exits the subway at the Astor Place stop, one sees not only the bas-relief beavers that decorate the station (a reference to the fur trade that created John Jacob Astor’s wealth), but also an arched, bricked-over doorway that reads “Clinton Hall” and once led directly from the subway platform into the Library. The Mercantile Library had clearly become a major New York City cultural institution.

By the early 1870s, the Mercantile Library was the fourth largest library in the country and the largest lending library in the United States. Only the Library of Congress, The Boston Public Library, and the Harvard University Library had larger collections. The reading room offered more than 400 magazines and newspapers, including a large number from around the world. The library contained over 120,000 volumes and there were nearly 13,000 members. A circulation of 1,000 books a day was the average in 1870, and this increased each year throughout the 1870s. By 1871, the Library was operating at three locations in Manhattan—the Clinton Hall building on Astor Place, at 149 Broadway, and at 598 Madison. There were also branches in ten neighboring towns including Jersey City, Elizabeth, and Paterson in New Jersey, Stamford and Norwalk in Connecticut, and Yonkers in New York. A home-delivery service was a popular and revenue-producing perquisite of membership. Over 11,000 books were delivered to homes in 1870. Initially this service utilized drop boxes throughout the city where members could deposit their book orders, but this system was soon replaced by a mail system. Blank orders, in the form of a square envelope imprinted with a U.S. two-cent postage stamp on the outside and a Mercantile Library five-sent stamp on the inside, were sold at the library for seven cents each. These blanks, when completed by the borrower with their request for books, could then be dropped in any U.S. Postal Service drop box, which—as the president of the Library noted—“were attached to almost every lamp-post with the city limits.” The orders were delivered to the library several times each day. The library had its own horses and wagons, which circulated throughout the city all day long delivering books to members. Often delivery took place within a few hours.

The library also remained committed to offering classes and lectures. Classes in French, German, elocution, phonography, and music were offered at Clinton Hall while lectures and readings were held at the new Steinway Hall on 14th Street. Opened in 1866 with a main auditorium of 2,000 seats, this hall became New York City’s artistic and cultural center and site of most of the Mercantile Library’s public lectures. It also housed the New York Philharmonic until Carnegie Hall opened in 1891. Frederick Douglass, the pre-eminent African American orator, abolitionist, and author, filled the house there in a Mercantile Library lecture on December 12, 1871. In December 1872, Bret Harte spoke on “The Argonauts of ’49,” and in January 1872, Henry Ward Beecher discussed “The Unconscious Influence of Democratic Principles.” The lecture there on January 24 by Samuel Clemens on Roughing It attracted one of the largest audiences ever assembled at a lecture in New York City. The New York Tribune described the event in its January 25 edition:

If there are those who fondly think that the popularity of the American humoristic school is on the decline, they would have been bravely undeceived by a visit to Steinway Hall last night. The most enormous audience ever collected at any lecture in New-York came together to listen to “Mark Twain’s” talk on “Roughing It.” Before the doors were opened $1,300 worth of tickets had been sold, and for some time before Mr. Clemens appeared the house was crammed in every part by an audience of over 2,000. A large number were turned away from the door, and after the close of the evening’s entertainment the officers of the Library Association warmly urged Mr. Clemens to repeat his lecture for the benefit of those who were disappointed.

The library clearly knew a winner when they saw one and brought Twain back for two talks in February 1873. These were held at the Academy of Music to accommodate the large crowds they drew, and both were sold out. These lectures added to the prestige of the Library as well as providing it with income, and membership continued to increase at a rapid pace.

By 1875, the Board of Directors was appealing to the Clinton Hall Association for more space. In 1879, Clinton Hall purchased four and half lots on the corner of Broadway and 37th Street for $180,000 with the idea that a new and larger building could be erected on this site. By 1889, however, the neighborhood surrounding the property no longer seemed appropriate for the library, and it was sold for $300,000. The Clinton Hall Association decided instead to remain on Astor Place and to demolish the building and erect a new fireproof structure with ample rental space that would bring income to the library. Finally, in 1890, the Library moved to temporary quarters at 67 Fifth Avenue and the old Opera House was razed. Construction was completed in March 1891 and the library opened on the sixth and seventh floors of the new building in November 1891. This structure remains there today with a Starbucks at its base and high-priced condominiums on its upper floors.

Membership had by this time declined to slightly over 5,000, although the library continued to be an important and respected force in New York cultural life. By 1893 circulation of fiction far outstripped circulation in all other categories: of the 169,627 books circulated, 92,374 were fiction.

A membership of 5,000 represented a sharp decline from the 13,000 members who had supported the Mercantile Library in 1870. In fact, by 1892 private libraries of all sizes were experiencing difficulties, including not only the Mercantile, but also both the Astor and Lenox libraries. In 1895, with the support of New York philanthropists led by attorney John Bigelow, the Astor and Lenox libraries joined with an entity called the Tilden Trust to create the New York Public Library. John Shaw Billings was named director of the new institution and a building was erected on the site of the Croton Reservoir on Fifth Avenue between 40th and 42nd streets. When the cornerstone of the new building was laid in 1902, it marked the beginning of a new era for libraries in the city and the beginning of a profound change in the focus and aspirations of the Mercantile Library.

The Twentieth Century

The Twentieth Century

The creation of the New York Public Library was not the only factor that affected the Library at the beginning of the twentieth century. The city had changed enormously in the last two decades. In 1880, horse-drawn trolleys and carriages carried New Yorkers through the city’s streets. By the 1890s, electric streetcars ran on the streets and in tunnels below ground. New York City’s first official subway system opened in Manhattan on October 27, 1904. By 1910, the streets were home to automobiles and bicyclists in great numbers on the surface as subways rumbled below. Nearly four-fifths of the city’s population was foreign-born or the children of foreign-born parents by the turn of the century, and many of these immigrant families were housed in four to six-story tenement buildings only a few blocks away from the library on Astor Place. On the lower east side 500,000 people per square mile lived without indoor plumbing.

Despite the emergence of this underclass, on many levels the city continued to thrive. The new models for city planning that were developed for the Columbian Exhibition in Chicago in 1893 began to have an impact on cities across America, and building boomed in the early twentieth century as Otis’s elevator and steel beam construction made skyscrapers a reality. Not since Olmstead and Vaux’s design for Central Park in 1850 had anything had as profound an effect on life in New York as did the advent of the skyscraper. With the completion of the Woolworth Building in 1913, New York as we know it today began to take shape.

The annual reports of the library at the turn of the century give no indication of what exactly led to the startling declines in membership at that time, though surely the advent of the public library and the emergence of the modern city with its emphasis on speed and innovation must not have helped. Though the library could no longer be said to be one of the city’s most important cultural institutions (its collection was now dwarfed by the collection in excess of one million volumes that was installed into the new public library on Fifth Avenue), it continued to collect books, offer classes and lectures, and play an important part in the life of its members. The delivery service continued to be a popular and profitable service of the library and was discontinued in 1917 only because wartime conditions made personal delivery within the bustling city impossible. Mail delivery was instituted in place of hand delivery and was thought to account for the large drop in circulation from 100,000 in 1910 to 60,000 in 1920.

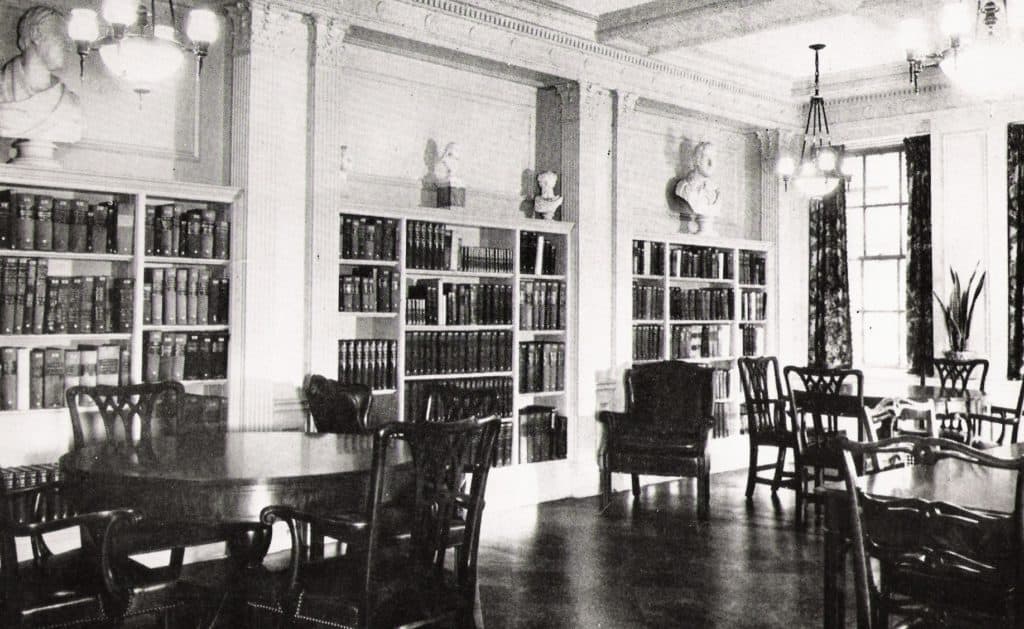

In 1920, the Astor Place building was sold to the Alexander Hamilton Institute. The library remained in the building, occupying the entire second floor. Because by this time only $80,000 remained on the mortgage, the Clinton Hall Association was able to create a sizeable endowment with the proceeds from the sale. However, the Board of Directors of the Mercantile Library was unhappy with the space that had been allotted them and vigorously lobbied for a new home devoted entirely to the Library. Finally, in 1932, having weathered the crash of the stock exchange relatively intact, the Clinton Hall Association agreed that it might indeed be prudent to invest in real estate. Through the efforts of the Head Librarian, the home of novelist F. Hopkinson Smith at 17 East 47th Street was purchased for a very good price. The building was razed and an eight-story “attractive, white marble, up-to-the-minute” modern structure was built.

The new building was designed by the architectural firm of Henry Otis Chapman, whose work included the Troy Public Library, the beautiful Hadley Library in Scranton, Pennsylvania, the Church of the Holy Trinity on 88th Street, and the Italianate apartment building at 952 Fifth Avenue. Half of the Clinton Hall Association’s funds were used to build the fireproof structure. It was built to contain 230,000 volumes and to be used only by the library. There was one stipulation, however. If the Mercantile Library Association encountered any financial difficulty, they were bound by the terms of their agreement with the Clinton Hall Association to turn over the seventh and eighth floors for use as rental space, with proceeds to support operations of the library. Despite the difficulties encountered by the library as the Great Depression dragged on, this clause was not implemented until 1980, when a long recession took its toll on membership and the rental income was necessary to preserve operations.

The Twenty-First Century

The Twenty-First Century

In 2001, after an examination of the needs of members and the shape the collection had organically taken over the library’s 180-year history, it became clear that in a city of major research libraries and special collections, the Mercantile Library could carve out a space as a home for literature. With this decision, the acquisitions committee began by augmenting the mystery and suspense collection, which contained many first editions and rare early mysteries. The Proust Society, founded by Harold Augenbraum, who was director at the time, attracted new members and created energy and enthusiasm that swept into other programs. Under Augenbraum, the library regained the firm financial footing it had lost in the early 1980s and began to be known for its strong Proust programming.

In 2005, with the advent of a new director, Noreen Tomassi, whose vision for a literary center devoted solely to fiction began to take shape almost immediately, the library was transformed first into the Mercantile Library Center for Fiction and then into its current incarnation as The Center for Fiction. By working not only to serve its membership of readers, but also to showcase writers with a series of book launches, readings by contemporary novelists, and collaborations with literary magazines such as Fiction, NOON, and Granta, it strengthened its reputation as an advocate for the art of fiction.

Its annual awards, given each year in December, became an important part of this newly envisioned mission to promote the reading, writing, and enjoyment of fiction in the United States. The Medal for Editorial Excellence (founded as the Maxwell E. Perkins Award for Distinguished Achievement in the Field of Fiction in 2005) honors recipients who over the course of their careers have discovered, nurtured, and championed writers of fiction in the United States. The First Novel Prize, established in 2006, is awarded to the best first novel published in the United States. It carries with it a $15,000 cash award and each year the winning novel is selected by a committee of distinguished American writers. Short-listed writers receive $1,000. The On Screen Award, established in 2018, honors groundbreaking original works for television or film that mirror the complexity and vision of great novels.

These awards are all part of an effort to bring national recognition to the art of fiction and to respond to changing conditions in the country at large. The art and business of fiction were clearly facing enormous challenges in America when the library made the decision to become The Center for Fiction. A 2004 National Endowment for the Arts report on the state of reading in America, entitled Reading at Risk, found that the reading of fiction had declined significantly and that fewer than half of American adults were reading novels or short stories of any kind. As a consequence, publishers were less willing to take risks, especially with literary fiction. On average, only thirteen percent of the books published in the United States were fiction. It seemed clear to the Board that a non-profit literary center that could become a constructive advocate for fiction in the United States was very much needed.

Throughout the history of the Mercantile Library, time and time again in the annual reports one sees the importance of fiction in the lives of its members. Despite the best efforts of the Board in the library’s early years to have clerks devote themselves to more serious subjects, almost from the beginning fiction or “works of fancy and the imagination” always had the largest circulation. Perhaps because the creation and telling of stories is fundamental to our lives as human beings, works of fiction have always answered some need, some basic human impulse, that non-fiction, however vigorously promoted, cannot address. The transformation of the Mercantile Library of New York into The Center for Fiction built upon the organization’s distinguished history and embraced that vital role as a nationally recognized institution.

In its beautiful new home for readers and writers in Brooklyn, The Center for Fiction engages the reading public by providing a broad range of in-person and online discussion groups, seminars, workshops, book clubs, readings, and other opportunities designed to bring readers at all levels in closer contact with fiction and its writers and teachers. It supports emerging and mid-career writers by providing fellowships, awards, low-cost workspace, writing workshops, and mentorships, as well as programs designed to help writers deal with the business of writing.

Perhaps most important, the creation of The Center for Fiction helps to spark a national conversation among readers, writers, educators, publishers, and technological innovators about the importance of fiction in our lives and the means to support and share it most broadly. Of course this new focus does not in any way diminish what has always been at the core of its mission and supports and celebrates the idea that was so fundamental to the clerks that gathered at Tontine’s Coffee House in 1820—that the art of fiction can open new worlds for all of us.