Yes, we could have played it safe and inaugurated this series with something by Chekhov or Gogol or by someone like Alice Munro, who writes nothing but short stories and who does so exquisitely. Instead, we’ve selected Sweethearts by Richard Ford, published nearly 24 years ago in his first story collection, Rock Springs, which was recently reissued by Atlantic Monthly Press. Ford is is best known today for his Bascombe novels—The Sportswriter, Independence Day, and The Lay of the Land—but he’s a master of the short story as well. We think Sweethearts is pitch-perfect and heart-rending—and a terrific example of everything a great short story should be.

Sweethearts by Richard Ford

was standing in the kitchen while Arlene was in the living room saying good-bye to her ex-husband, Bobby. I had already been out to the store for groceries and come back and made coffee, and was drinking it and staring out the window while the two of them said whatever they had to say. It was a quarter to six in the morning.

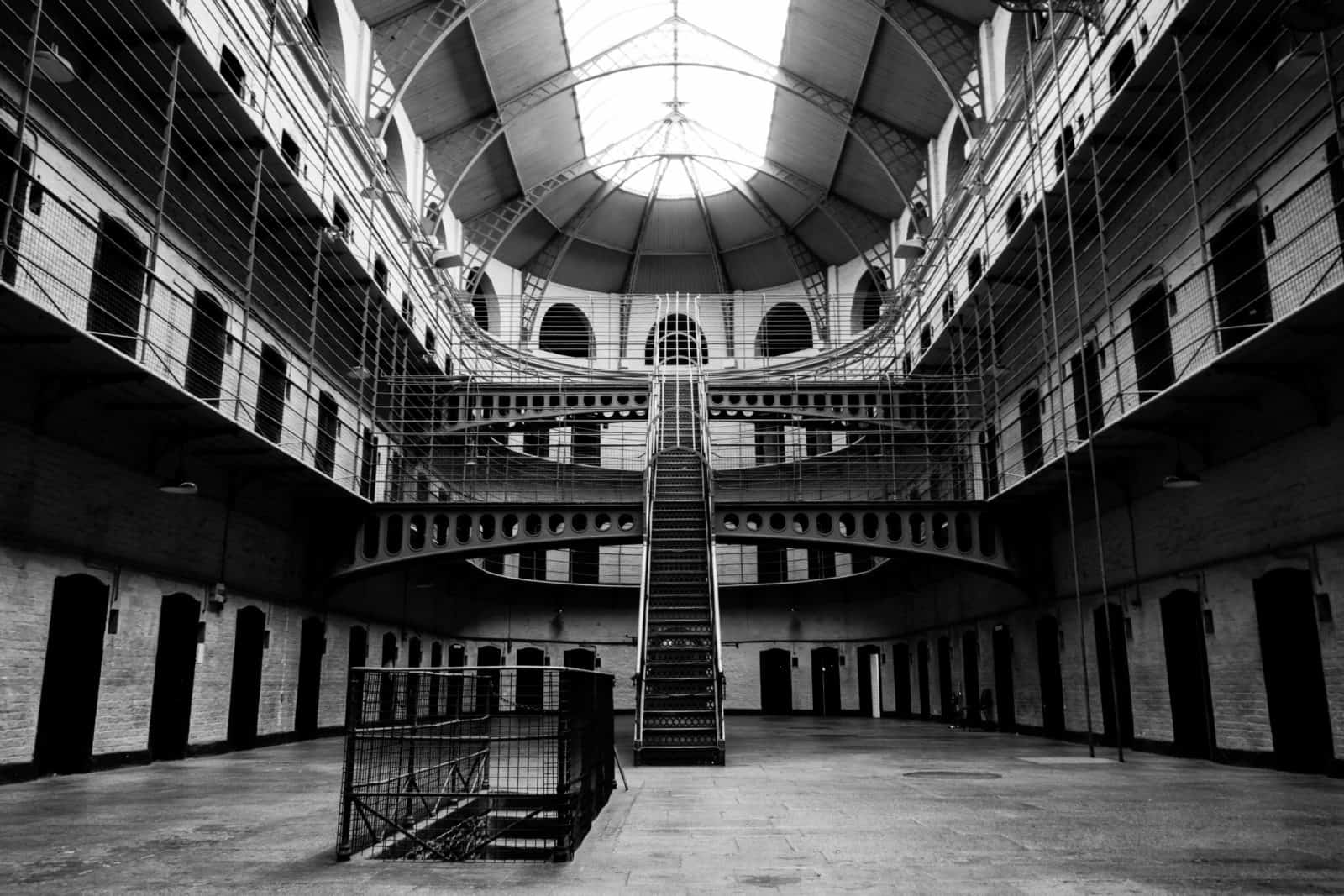

This was not going to be a good day in Bobby’s life, that was clear, because he was headed to jail. He had written several bad checks, and before he could be sentenced for that he had robbed a convenience store with a pistol—completely gone off his mind. And everything had gone to hell, as you might expect. Arlene had put up the money for his bail, and there was some expensive talk about an appeal. But there wasn’t any use to that. He was guilty. It would cost money and then he would go to jail anyway.

Arlene had said she would drive him to the sheriff’s department this morning, if I would fix him breakfast, so he could surrender on a full stomach and that had seemed all right. Early in the morning Bobby had brought his motorcycle around to the backyard and tied up his dog to the handlebars. I had watched him from the window. He hugged the dog, kissed it on the head and whispered something in its ear, then came inside. The dog was a black Lab, and it sat beside the motorcycle now and stared with blank interest across the river at the buildings of town, where the sky was beginning to turn pinkish and the day was opening up. It was going to be our dog for a while now, I guessed.

Arlene and I had been together almost a year. She had divorced Bobby long before and had gone back to school and gotten real estate training and bought the house we lived in, then quit that and taught high school a year, and finally quit that and just went to work in a bar in town, which is where I came upon her. She and Bobby had been childhood sweethearts and run crazy for fifteen years. But when I came into the picture, things with Bobby were settled, more or less. No one had hard feelings left, and when he came around I didn’t have any trouble with him. We had things we talked about—our pasts, our past troubles. It was not the worst you could hope for.

From the living room I heard Bobby say, “So how am I going to keep up my self-respect. Answer me that. That’s my big problem.”

“You have to get centered,” Arlene said in an upbeat voice. “Be within yourself if you can.”

“I feel like I’m catching a cold right now,” Bobby said. “On the day I enter prison I catch cold.”

“Take Contac,” Arlene said. “I’ve got some some-where.” I heard a chair scrape the floor. She was going to get it for him.

“I already took that,” Bobby said. “I had some at home.”

“You’ll feel better then,” Arlene said. “They’ll have Contac in prison.”

“I put all my faith in women,” Bobby said softly. “I see now that was wrong.”

“I couldn’t say,” Arlene said. And then no one spoke.

I looked out the window at Bobby’s dog. It was still staring across the river at town as if it knew about something there.

The door to the back bedroom opened then, and my daughter Cherry came out wearing her little white nightgown with red valentines on it. BE MINE was on all the valentines. She was still asleep, though she was up. Bobby’s voice had waked her up.

“Did you feed my fish?” she said and stared at me. She was barefoot and holding a doll, and looked pretty as a doll herself.

“You were asleep already,” I said.

She shook her head and looked at the open living-room door. “Who’s that?” she said.

“Bobby’s here,” I said. “He’s talking to Arlene.”

Cherry came over to the window where I was and looked out at Bobby’s dog. She liked Bobby, but she liked his dog better. “There’s Buck,” she said. Buck was the dog’s name. A tube of sausage was lying on the sink top and I wanted to cook it, for Bobby to eat, and then have him get out. I wanted Cherry to go to school, and for the day to flatten out and hold fewer people in it. Just Arlene and me would be enough.

“You know, Bobby, sweetheart,” Arlene said now in the other room, “in our own lifetime we’ll see the last of the people who were born in the nineteenth century. They’ll all be gone soon. Every one of them.”

“We should’ve stayed together, I think,” Bobby whispered. I was not supposed to hear that, I knew. “I wouldn’t be going to prison if we’d loved each other.”

“I wanted to get divorced, though,” Arlene said.

“That was a stupid idea.”

“Not for me it wasn’t,” Arlene said. I heard her stand up.

“It’s water over the bridge now, I guess, isn’t it?” I heard Bobby’s hands hit his knees three times in a row.

“Let’s watch TV,” Cherry said to me, and went and turned on the little set on the kitchen table. There was a man talking on a news show.

“Not loud,” I said. “Keep it soft.”

“Let’s let Buck in,” she said. “Buck’s lonely.”

“Leave Buck outside,” I said.

Cherry looked at me without any interest. She left her doll on top of the TV. “Poor Buck,” she said. “Buck’s crying. Do you hear him?”

“No,” I said. “I can’t hear him.”

Bobby ate his eggs and stared out the window as if he was having a hard time concentrating on what he was doing. Bobby is a handsome small man with thick black hair and pale eyes. He is likable, and it is easy to see why women would like him. This morning he was dressed in jeans and a red T-shirt and boots. He looked like somebody on his way to jail.

He stared out the back window for a long time and then he sniffed and nodded. “You have to face that empty moment, Russ.” He cut his eyes at me. “How often have you done that?”

“Russ’s done that, Bob,” Arlene said. “We’ve all done that now. We’re adults.”

“Well, that’s where I am right now,” Bobby said. “I’m at the empty moment here. I’ve lost everything.”

“You’re among friends, though, sweetheart.” Arlene smiled. She was smoking a cigarette.

“I’m calling you up. Guess who I am,” Cherry said to Bobby. She had her eyes squeezed tight and her nose and mouth pinched up together. She was moving her head back and forth.

“Who are you?” Bobby said and smiled.

“I’m the bumblebee.”

“Can’t you fly?” Arlene said.

“No. My wings are much too short and I’m too fat.” Cherry opened her eyes at us suddenly.

“Well, you’re in big trouble then,” Arlene said.

“A turkey can go forty-five miles an hour,” Cherry said and looked shocked.

“Go change your clothes,” I said.

“Go ahead now, sweetheart.” Arlene smiled at her. “I’ll come help you.”

Cherry squinted at Bobby, then went back to her room. When she opened her door I could see her aquarium in the dark against the wall, a pale green light with pink rocks and tiny dots of fish.

Bobby ran his hands back through his hair and stared up at the ceiling. “Okay,” he said, “here’s the awful criminal now, ready for jail.” He looked at us then, and he looked wild, as wild and desperate as I have ever seen a man look. And it was not for no reason.

“That’s off the wall,” Arlene said. “That’s just completely boring. I’d never be married to a man who was a fucking criminal.” She looked at me, but Bobby looked at me too.

“Somebody ought to come take her away,” Bobby said. “You know that, Russell? Just put her in a truck and take her away. She always has such a wonderful fucking outlook. You wonder how she got in this fix here.” He looked around the little kitchen, which was shabby and white. At one time Arlene’s house had been a jewelry store, and there was a black security camera above the kitchen door, though it wasn’t connected now.

“Just try to be nice, Bobby,” Arlene said.

“I just oughta slap you,” Bobby said, and I could see his jaw muscles tighten, and I thought he might slap her then. In the bedroom I saw Cherry standing naked in the dark, sprinkling food in her aquarium. The light made her skin look the color of water.

“Try to calm down, Bob,” I said and stayed put in my chair. “We’re all your friends.”

“I don’t know why people came out here,” Bobby said. “The West is fucked up. It’s ruined. I wish somebody would take me away from here.”

“Somebody’s going to, I guess,” Arlene said, and I knew she was mad at him and I didn’t blame her, though I wished she hadn’t said that.

Bobby’s blue eyes got small, and he smiled at her in a hateful way. I could see Cherry looking in at us. She had not heard this kind of talk yet. Jail talk. Mean talk. The kind you don’t forget. “Do you think I’m jealous of you two?” Bobby said. “Is that it?”

“I don’t know what you are,” Arlene said.

“Well, I’m not. I’m not jealous of you two. I don’t want a kid. I don’t want a house. I don’t want anything you got. I’d rather go to Deer Lodge.” His eyes flashed out at us.

“That’s lucky, then,” Arlene said. She stubbed out her cigarette on her plate, blew smoke, then stood up to go help Cherry. “Here I am now, hon,” she said and closed the bedroom door.

Bobby sat at the kitchen table for a while and did not say anything. I knew he was mad but that he was not mad at me. Probably, in fact, he couldn’t even think why I was the one here with him now—some man he hardly knew, who slept with a woman he had loved all his life and, at that moment, thought he still loved, but who—among his other troubles— didn’t love him anymore. I knew he wanted to say that and a hundred things more then. But words can seem weak. And I felt sorry for him, and wanted to be as sympathetic as I could be.

“I don’t like to tell people I’m divorced, Russell,” Bobby said very clearly and blinked his eyes. “Does that make any sense to you?” He looked at me as if he thought I was going to lie to him, which I wasn’t.

“That makes plenty of sense,” I said.

“You’ve been married, haven’t you? You have your daughter.”

“That’s right,” I said.

“You’re divorced, aren’t you?”

“Yes.”

Bobby looked up at the security camera above the kitchen door, and with his finger and thumb made a gun that he pointed at the camera, and made a soft popping with his lips, then he looked at me and smiled. It seemed to make him calmer. It was a strange thing.

“Before my mother died, okay?” Bobby said, “I used to call her on the phone. And it took her a long time to get out of bed. And I used to wait and wait and wait while it rang. And sometimes I knew she just wouldn’t answer it, because she couldn’t get up. Right? And it would ring forever because it was me, and I was willing to wait. Sometimes I’d just let it ring, and so would she, and I wouldn’t know what the fuck was going on. Maybe she was dead, right?” He shook his head.

“I’ll bet she knew it was you,” I said. “I bet it made her feel better.”

“You think?” Bobby said.

“It’s possible. It seems possible.”

“What would you do, though?” Bobby said. He bit his lower lip and thought about the subject. “When would you let it stop ringing? Would you let it go twenty-five or fifty? I wanted her to have time to decide. But I didn’t want to drive her crazy. Okay?”

“Twenty-five seems right,” I said.

Bobby nodded. “That’s interesting. I guess we all do things different. I always did fifty.

“That’s fine.”

“Fifty’s way too many, I think.”

“It’s what you think now,” I said. “But then was different.”

“There’s a familiar story,” Bobby said.

“It’s everybody’s story,” I said. “The then-and-now story.”

“We’re just short of paradise, aren’t we, Russell?”

“Yes we are,” I said.

Bobby smiled at me then in a sweet way, a way to let anyone know he wasn’t a bad man, no matter what he’d robbed.

“What would you do if you were me,” Bobby said, “if you were on your way to Deer Lodge for a year?”

I said, “I’d think about when I was going to get out, and what kind of day that was going to be, and that it wasn’t very far in the future.”

“I’m just afraid it’ll be too noisy to sleep in there,” he said and looked concerned about that.

“It’ll be all right,” I said. “A year can go by quick.”

“Not if you never sleep,” he said. “That worries me.”

“You’ll sleep,” I said. “You’ll sleep fine.”

And Bobby looked at me then, across the kitchen table, like a man who knows half of something and who is supposed to know everything, who sees exactly what trouble he’s in and is scared to death by it.

“I feel like a dead man, you know?” And tears suddenly came into his pale eyes. “I’m really sorry,” he said. “I know you’re mad at me. I’m sorry.” He put his head in his hands then and cried. And I thought: What else could he do? He couldn’t avoid this now. It was all right.

“It’s okay, bud,” I said.

“I’m happy for you and Arlene, Russ,” Bobby said, his face still in tears. “You have my word on that. I just wish she and I had stayed together, and I wasn’t such an asshole. You know what I mean?”

“I know exactly,” I said. I did not move to touch him, though maybe I should have. But Bobby was not my brother, and for a moment I wished I wasn’t tied to all this. I was sorry I had to see any of it, sorry that each of us would have to remember it.

On the drive to town Bobby was in better spirits. He and Cherry sat in the back, and Arlene in the front. I drove. Cherry held Bobby’s hand and giggled, and Bobby let her put on his black silk Cam Ranh Bay jacket he had won playing cards, and Cherry said that she had been a soldier in some war.

The morning had started out sunny, but now it had begun to be foggy, though there was sun high up, and you could see the Bitterroots to the south. The river was cool and in a mist, and from the bridge you could not see the pulp yard or the motels a half mile away.

“Let’s just drive, Russ,” Bobby said from the backseat. “Head to Idaho. We’ll all become Mormons and act right.”

“That’d be good, wouldn’t it?” Arlene turned and smiled at him. She wasn’t mad now. It was her nicest trait, not to stay mad at anybody for long.

“Good day,” Cherry said.

“Who’s that talking,” Bobby asked.

“I’m Paul Harvey,” Cherry said.

“He always says that, doesn’t he?” Arlene said.

“Good day,” Cherry said again.

“That’s all Cherry’s going to say all day now, Daddy,” Arlene said to me.

“You’ve got a honeybunch back here,” Bobby said and tickled Cherry’s ribs. “She’s her daddy’s girl all the way.”

“Good day,” Cherry said again and giggled.

“Children pick up your life, don’t they, Russ?” Bobby said. “I can tell that.”

“Yes, they do,” I said. They can.”

“I’m not so sure about that one back there, though,” Arlene said. She was dressed in a red cowboy shirt and jeans, and she looked tired to me. But I knew she didn’t want Bobby to go to jail by himself.

“I am. I’m sure of it,” Bobby said, and then didn’t say anything else.

We were on a wide avenue where it was foggy, and there were shopping centers and drive-ins and car lots. A few cars had their headlights on, and Arlene stared out the window at the fog. “You know what I used to want to be?” she said.

“What?” I said when no one else said anything.

Arlene stared a moment out the window and touched the corner of her mouth with her fingernail and smoothed something away. “A Tri-Delt,” she said and smiled. “I didn’t really know what they were, but I wanted to be one. I was already married to him, then, of course. And they wouldn’t take married girls in.”

“That’s a joke,” Bobby said, and Cherry laughed.

“No. It’s not a joke,” Arlene said. “It’s just something you don’t understand and that I missed out on in life.” She took my hand on the seat and kept looking out the window. And it was as if Bobby wasn’t there then, as if he had already gone to jail.

“What I miss is seafood,” Bobby said in an ironic way. “Maybe they’ll have it in prison.

You think they will?”

“I hope so, if you miss it,” Arlene said.

“I bet they will,” I said. “I bet they have fish of some kind in there.”

“Fish and seafood aren’t the same,” Bobby said.

We turned onto the street where the jail was. It was an older part of town and there were some old white two-story residences that had been turned into lawyers’ offices and bail bondsmen’s rooms. Some bars were farther on, and the bus station. At the end of the street was the courthouse. I slowed so we wouldn’t get there too fast.

“You’re going to jail right now,” Cherry said to Bobby.

“Isn’t that something?” Bobby said. I watched him up in the rearview; he looked down at Cherry and shook his head as if it amazed him.

“I’m going to school soon as that’s over,” Cherry said.

“Why don’t I just go to school with you?” Bobby said. “I think I’d rather do that.”

“No sir,” Cherry said.

“Oh Cherry, please don’t make me go to jail. I’m innocent,” Bobby said. “I don’t want to go.”

Too bad,” Cherry said and crossed her arms.

“Be nice,” Arlene said. Though I know Cherry thought she was being nice. She liked Bobby.

“She’s teasing, Mama. Aren’t we, Cherry baby? We understand each other.”

“I’m not her mama,” Arlene said.

“That’s right, I forgot,” Bobby said. And he widened his eyes at her. “What’s your hurry, Russ?” Bobby said, and I saw I had almost come to a stop in the street. The jail was a half block ahead of us. It was a tall modern building built on the back of the old stone courthouse. Two people were standing in the little front yard looking up at a window. A station wagon was parked on the street in front. The fog had begun to burn away now.

“I didn’t want to rush you,” I said.

“Cherry’s already dying for me to go in there, aren’t you, baby?”

“No, she’s not. She doesn’t know anything about that,” Arlene said.

“You go to hell,” Bobby said. And he grabbed Arlene’s shoulder with his hand and squeezed it back hard against the seat. “This is not your business, it’s not your business at all. Look, Russ,” Bobby said, and he reached in the black plastic bag he was taking with him and pulled a pistol out of it and threw it over onto the front seat between Arlene and me. “I thought I might kill Arlene, but I changed my mind.” He grinned at me, and I could tell he was crazy and afraid and at the end of all he could do to help himself anymore.

“Jesus Christ,” Arlene said. “Jesus, Jesus Christ.”

“Take it, goddamn it. It’s for you,” Bobby said with a crazy look. “It’s what you wanted. Boom,” Bobby said. “Boom-boom-boom.”

“I’ll take it,” I said and pulled the gun under my leg. I wanted to get it out of sight.

“What is it?” Cherry said. “Lemme see.” She pushed up to see.

“It’s nothing, honey,” I said. “Just something of Bobby’s.”

“Is it a gun?” Cherry said.

“No, sweetheart,” I said, “it’s not.” I pushed the gun down on the floor under my foot. I did not know if it was loaded, and I hoped it wasn’t. I wanted Bobby out of the car then. I have had my troubles, but I am not a person who likes violence or guns. I pulled over to the curb in front of the jail, behind the brown station wagon. “You better make a move now,” I said to Bobby. I looked at Arlene, but she was staring straight ahead. I know she wanted Bobby gone, too.

“I didn’t plan this. This just happened,” Bobby said. “Okay? You understand that? Nothing’s planned.”

“Get out,” Arlene said and did not turn to look at him.

“Give Bobby back his jacket,” I said to Cherry.

“Forget it, it’s yours,” Bobby said. And he grabbed his plastic string bag.

“She doesn’t want it,” Arlene said.

“Yes I do,” Cherry said. “I want it.”

“Okay,” I said. “That’s nice, sweetheart.”

Bobby sat in the seat and did not move then. None of us moved in the car. I could see out the window into the little jailyard. Two Indians were sitting in plastic chairs outside the double doors. A man in a gray uniform stepped out the door and said something to them, and one got up and went inside. There was a large, red-faced woman standing on the grass, staring at our car.

I got out and walked around the car to Bobby’s door and opened it. It was cool out, and I could smell the sour pulp-mill smell being held in the fog, and I could hear a car laying rubber on another street.

“Bye-bye, Bobby,” Cherry said in the car. She reached over and kissed him.

“Bye-bye,” Bobby said. “Bye-bye.”

The man in the gray uniform had come down off the steps and stopped halfway to the car, watching us. He was waiting for Bobby, I was sure of that.

Bobby got out and stood up on the curb. He looked around and shivered. He looked cold and I felt bad for him. But I would be glad when he was gone and I could live a normal life again.

“What do we do now?” Bobby said. He saw the man in the gray uniform, but would not look at him. Cherry was saying something to Arlene in the car, but Arlene didn’t say anything. “Maybe I oughta run for it,” Bobby said, and I could see his pale eyes were jumping as if he was eager for something now, eager for things to happen to him.

Suddenly he grabbed both my arms and pushed me back against the door and pushed his face right up to my face. “Fight me,” he whispered and smiled a wild smile. “Knock the shit out of me. See what they do.” I pushed against him, and for a moment he held me there, and I held him, and it was as if we were dancing without moving. And I smelled his breath and felt his cold, thin arms and his body struggling against me, and I knew what he wanted was for me not to let him go, and for all this to be a dream he could forget about.

“What’re you doing?” Arlene said, and she turned around and glared at us. She was mad, and she wanted Bobby to be in jail now. “Are you kissing each other?” she said. “Is that what you’re doing? Kissing good-bye?”

“We’re kissing each other, that’s right,” Bobby said. “That’s what we’re doing. I always wanted to kiss Russell. We’re queers.” He looked at her then, and I know he wanted to say something more to her, to tell her that he hated her or that he loved her or wanted to kill her or that he was sorry. But he couldn’t come to the words for that. And I felt him go rigid and shiver, and I didn’t know what he would do. Though I knew that in the end he would give in to things and go along without a struggle. He was not a man to struggle against odds. That was his character, and it is the character of many people.

“Isn’t this the height of something, Russell?” Bobby said, and I knew he was going to be calm now. He let go my arms and shook his head. “You and me out here like trash, fighting over a woman.”

And there was nothing I could say then that would save him or make life better for him at that moment or change the way he saw things. And I went and got back in the car while Bobby turned himself in to the uniformed man who was waiting.

I drove Cherry to school then, and when I came back outside Arlene had risen to a better mood and suggested that we take a drive. She didn’t start work until noon, and I had the whole day to wait until Cherry came home. “We should open up some emotional distance,” she said. And that seemed right to me.

We drove up onto the interstate and went toward Spokane, where I had lived once and Arlene had, too, though we didn’t know each other then—the old days, before marriage and children and divorce, before we met the lives we would eventually lead, and that we would be happy with or not.

We drove along the Clark Fork for a while, above the fog that stayed with the river, until the river turned north and there seemed less reason to be driving anywhere. For a time I thought we should just drive to Spokane and put up in a motel. But that, even I knew, was not a good idea. And when we had driven on far enough for each of us to think about things besides Bobby, Arlene said, “Let’s throw that gun away, Russ.” I had forgotten all about it, and I moved it on the floor with my foot to where I could see it—the gun Bobby had used, I guessed, to commit crimes and steal people’s money for some crazy reason.

“Let’s throw it in the river,” Arlene said. And I turned the car around.

We drove back to where the river turned down even with the highway again, and went off on a dirt-and-gravel road for a mile. I stopped under some pine trees and picked up the gun and looked at it to see if it was loaded and found it wasn’t. Then Arlene took it by the barrel and flung it out the window without even leaving the car, spun it not very far from the bank, but into deep water where it hit with no splash and was gone in an instant.

“Maybe that’ll change his luck,” I said. And I felt better about Bobby for having the gun out of the car, as if he was safer now, in less danger of ruining his life and other people’s, too.

When we had sat there for a minute or two, Arlene said, “Did he ever cry? When you two were sitting in the kitchen? I wondered about that.”

“No,” I said. “He was scared. But I don’t blame him for that.”

“What did he say?” And she looked as if the subject interested her now, whereas before it hadn’t.

“He didn’t say too much. He said he loved you, which I knew anyway.”

Arlene looked out the side window at the river. There were still traces of fog that had not burned off in the sun. Maybe it was nine o’clock in the morning. You could hear the interstate back behind us, trucks going east at high speed.

“I’m not real unhappy that Bobby’s out of the picture now. I have to say that,” Arlene said. “I should be more—I guess—sympathetic. It’s hard to love pain if you’re me, though.”

“It’s not really my business,” I said. And I truly did not think it was or ever would be. It was not where my life was leading me, I hoped.

“Maybe if I’m drunk enough someday I’ll tell you about how we got apart,” Arlene said. She opened the glove box and got out a package of cigarettes and closed the latch with her foot. “Nothing should surprise anyone, though, when the sun goes down. I’ll just say that. It’s all just melodrama.” She thumped the pack against the heel of her hand and put her feet up on the dash. And I thought about poor Bobby, being frisked and handcuffed out in the yard of the jail and being led away to become a prisoner, like a piece of useless machinery. I didn’t think anyone could blame him for anything he ever thought or said or became after that. He could die in jail and we would still be outside and free. “Would you tell me something if I asked you?” Arlene said, opening her package of cigarettes. “Your word’s worth something, isn’t it?”

“To me it is,” I said.

She looked over at me and smiled because that was a question she had asked me before, and an answer I had said. She reached across the car seat and squeezed my hand, then looked down the gravel road to where the Clark Fork went north and the receding fog had changed the colors of the trees and made them greener and the moving water a darker shade of blue-black.

“What do you think when you get in bed with me every night? I don’t know why I want to know that. I just do,” Arlene said. “It seems important to me.”

And in truth I did not have to think about that at all, because I knew the answer, and had thought about it already, had wondered, in fact, if it was in my mind because of the time in my life it was, or because a former husband was involved, or because I had a daughter to raise alone, and no one else I could be absolutely sure of.

“I just think,” I said, “here’s another day that’s gone. A day I’ve had with you. And now it’s over.”

“There’s some loss in that, isn’t there?” Arlene nodded at me and smiled.

“I guess so,” I said.

“It’s not so all-bad though, is it? There can be a next day.”

That’s true,” I said.

“We don’t know where any of this is going, do we?” she said, and she squeezed my hand tight.

“No,” I said. And I knew that was not a bad thing at all, not for anyone, in any life.

“You’re not going to leave me for some other woman, now, are you? You’re still my sweetheart. I’m not crazy, am I?”

“I never thought that,” I said.

“It’s your hole card, you know,” Arlene said. “You can’t leave twice. Bobby proved that.” She smiled at me again.

And I knew she was right about that, though I did not want to hear about Bobby anymore for a while. He and I were not alike. Arlene and I had nothing to do with him. Though I knew, then, how you became a criminal in the world and lost it all. Somehow, and for no apparent reason, your decisions got tipped over and you lost your hold. And one day you woke up and you found yourself in the very situation you said you would never ever be in, and you did not know what was most important to you anymore. And after that, it was all over. And I did not want that to happen to me—did not, in fact, think it ever would. I knew what love was about. It was about not giving trouble or inviting it. It was about not leaving a woman for the thought of another one. It was about never being in that place you said you’d never be in. And it was not about being alone. Never that. Never that.

ROCK SPRINGS © 1987 by Richard Ford, and reprinted with the permission of the publisher, Grove/Atlantic, Inc.