Frances was fifty-nine and Peanut was twenty-five, and because of this they were often distracted by the looks of others in public. Usually people assumed Frances was Peanut’s mother and gave the pair bright encouraging smiles, happy to see a mother and daughter so glad to be near each other. But then Peanut would give Frances a long open kiss on the mouth and every smiler would stiffen, fascinated with disgust.

When the two announced their plan to adopt a dog, everyone disapproved. Peanut’s friends assumed domineering parental tones. They seemed to suggest Peanut would leave the animal somewhere or forget to feed it. “Plus, what if you and Frances break up?” one of them snorted.

Peanut quietly considered replacing all of her friends with dogs. She explained that she had already paid for the dog, which was a lie. She hadn’t even met the dog. He was 400 miles away, in Cumberland, Pennsylvania. He was three months old and his name was Tony. Peanut and Frances had spent hours trolling petfinder.com and gasped when his small triangle face appeared on the screen. He looked unmistakably like a Chihuahua, but had been described on the site as an unknown mixed breed. The dog had chipmunk coloring, with a dark muzzle and large foxish ears. He was pictured in a woman’s dry pink hands, grasped by the torso, with the bratty oblivious expression of a king’s baby, white chest exposed, little orange legs dangling.

Peanut had filled out a ten-page application online and then got an email from Tony’s rescuer with more questions. Her name was Gail and she wanted to know everything. Would Peanut leave him alone for long periods of time? No, she would not. Was Peanut thinking of moving any time soon, or having a baby? No, never. Peanut wrote several careful emails detailing her unconditional commitment to the animal and then Frances had to do the same.

After an unbearable dayof waiting, Gail wrote back. Alright I’m convinced.

“So we’re really doing this?” Peanut said to Frances.

“Really.”

“I can’t believe you’re up for driving so far. I’ve never met someone so willing to go along with my wild plans.”

“Some people would consider that a character defect.”

“No. You are so good to me,” Peanut said and Frances glowed in agreement.

***

During the week before their drive, Frances flew to San Francisco on a gig with her band, The Invisible Committee. She didn’t pick up her phone, though Peanut called several times, leaving lewd messages. Frances had been too focused on meeting people at parties, grinning hotly at compliments from strangers. She had a distinct allure, and women of all sorts invited her to fuck them. But Frances didn’t want to fuck them. While she developed crushes on various people, their advances often pitched her into despair. Mostly they were fans, beaming with anticipation, waiting for the right moment to corner her. Frances hated for strangers to pounce. It made her feel like shewas the commodity, not her work. “People wanna bite my aura,” she said to her band mates and they all rolled their eyes. But it was true.

On her last night, Frances slunk back to her hotel room and crawled into bed, relishing the quiet. Frances loved to be alone. She groomed herself ritualistically, flossing before the mirror in a striped robe. She studied her face and then thought of Peanut’s face, her bright animal eyes. Frances couldn’t help but measure their life spans alongside each other. She is like a vampire, Frances thought.She is watching a human wither.

Instead of calling Peanut back, Frances sent her several short romantic emails, which both delighted and enraged Peanut. Some were song lyrics, of which Peanut’s favorite read: I am devoted to your brain and ass and how profoundly they speak. My love is a shaking cup. A little Frenchman.

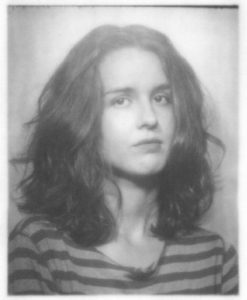

Peanut smiled reading the email but afterward felt tricked. She didn’t at all like being charmed out of a rageful state and so she willed herself back into anger. Peanut dwelled on the humiliation of leaving dirty messages that went unreturned. She flipped through her notebook, sprawled stomach-down in bed, calves crossed in the air. She loved to read her old poems. They are like photographs, she thought. There’s so much evidence of me.

Peanut turned off the light and laid in the dark imagining she were tough and un-interested in love. Half into a dream, she promised herself she would behave coldly toward Frances as soon as she saw her, which would be the morning of their long drive to fetch Tony.

She had active, colorful nightmares of the apocalypse. Bombs going off, smoke floating from collapsed buildings, people left twitching in the street. Peanut woke up with bags under her eyes. She looked at her phone and, seeing that Frances hadn’t called, an old sadness swooped over her. Whenever Frances vanished, it felt like the old days, before their relationship, back when Peanut was still plotting ways to get near her.

Peanut had first glimpsed Frances singing onstage at a bar, leaning into dusty beams of red and pink light, rope-veins running up her forearms. She sang in a low androgynous voice that broke into little shouts, her manlike mouth almost touching the microphone. Peanut had come to the show with a friend but quickly abandoned this person to make brave conversation with Frances when the next band came on. Frances was friendly and responsive, but ultimately appeared bored. It took months for her to act even remotely romantic toward Peanut and during this excruciating wait period, Peanut had talked to herself in mannish tones and masturbated with a galaxy-print sheet hiked up over her face.

***

On the day of their drive, Peanut sat waiting on her stoop. She wore a sheer, ratty t-shirt tucked into dark denim shorts and white tennis shoes without socks. Beside her feet sat a large straw bag with a rope strap.

Peanut had lived in the same apartment on the lower East side since childhood but in the last year, the building had changed hands and since the sale, it kept morphing. First, all of the stone floral ornaments were torn from the façade and then after months of misguided upscaling, the building wound up looking like a pizza chain with pretensions. Cheap wrought iron handrails led to a yellow wood door that was often greasy with oil. “It’s very Epcot,” Frances had sneered the first time she came over. “Sort of a suburban take on urban.”

Peanut considered how she might appear waiting on her stoop, bent over her marble notebook, legs crossed, big tortoise sunglasses between forward-falling hair. She smacked a mosquito on her calf.

***

Frances pulled up to the curb in her olive pick-up truck, one arm out the window. She had a skinny creased face and center-parted Jesusy hair that she kept dirty to darken the gray. “Hey,” she said, her voice tender and smug at once.

In the car, Peanut smiled madly. The two held each other and made out greedily for a bit. Then Frances looked nervously out the window, adjusting her black horn-rimmed glasses.

“Oh, come on.” Peanut rolled her eyes. “Relax.” Her voice had a fluty underwater quality, a subtle echo chamber.

“You come on. You’re a sweet little bunny and I’m this gnarly old man. I mean if someone wanted to murder one of us to make a point, they would murder me.”

Peanut pointed to a couple of old women sitting on a stoop across the street. They were staring. “Those two absolutely want to murder you. Look at them,” she chuckled. “It’s like they don’t even care that we can see them.”

“They want us to see. They want us to know what they think of us.”

“Right.” Peanut tipped her head onto Frances’ shoulder. “That I’m some victim.”

“What do you mean?”

“Well you’re the old pervert, right? But I’m considered this, like,idiot child with daddy issues. Even your friends treat me like that.”

“Like you have daddy issues?”

“Like I’m an idiot. They don’t really,” Peanut paused, “engage me. I mean, the level of inquiry is low. Like, if we get dinner, they pretend to be talking to both of us, but they’re making eye contact with you the whole time. And then you and whoever just wind up prompting each other’s monologues. It reminds me of being at dinner parties with my parents as a kid. Back when I was three feet tall and really was invisible unless I was being bad.”

“God. You have to tell me when you feel like that.” Frances pinched Peanut’s mid-section affectionately. It was a measuring pinch. A butcher’s pinch.

“Okay.” Peanut sat up in her seat and remembered that she was angry at Frances.

“Or maybe I just shouldn’t go. I mean out with you and your friends. I’m not interested in winning anyone’s approval.” She opened a greasy paper bag full of broken cookies and scones from the bakery where she worked. “You want?” She put the open bag between their seats.

“No. I’m starting to look like a skeleton with a watermelon around its waist,” Frances smirked and then dug her hand into the bag, lifting out a crumbly cookie half.

Peanut laughed and poked Frances’s hip. “I like it.”

“It? That’s great. So it exists.”

“Oh darling, stop. Anyway I only took this stuff because it was free. I’m actually pretty revolted by sweets at this point.” Peanut began rummaging through her straw bag and pulled out a CD book covered with peeling stickers. She flipped through the plastic pages.

“Can we not listen to The Smiths,” Frances said, steering back onto the road.

“Why not?”

“His voice is so endless and droning. It just makes me sad.”

“That’s the whole point.”

“Well, it doesn’t speak to my sadness, it produces sadness.” Frances reached back into the paper bag and felt around. “What are these hard pieces?”

“Scones. They’re sort of awful.” Peanut settled on a Gram Parsons compilation and Frances nodded approvingly. “Tell me about your trip,” Peanut said in a soft guarded voice, sliding the CD in. Dark End of the Street began to play.

“We stayed at the grossest Motel 6. There was this place next door called Safari, with a big sign listing everything inside. It said all new live girls, rib eye, beer garden. I loved that it said all new live girls. Like, we killed the ones that were here yesterday. They’re in the dumpster. These are the new ones.”

“What’s a beer garden?”

“I don’t know. I think of fat men rubbing beers dangling from tree branches on their naked stomachs. Of course the place was really dark. And the parking lot was full of cars.”

“That’s so sci-fi. Every man a little king,” Peanut said excitedly. “You should’ve gone inside.”

“I know. I wanted to.”

“You would have managed to somehow have a great time. You’d have met some amazing woman,” Peanut said mockingly.

“Yeah and we would have had the most amazing conversation. While she was giving me a lap dance.”

Peanut pulled the visor mirror down and stared at her face. “Have you ever had a lap dance?”

“I’ve had opportunities. At Esther’s fortieth there were strippers but I resisted. Something about the idea of tons of people watching me get a lap dance.”

Peanut imagined Esther under the grinding pelvis of a stripper. She was a rather conceited woman with close-cropped red hair and a birdlike face. She had once strolled over to Peanut at a party and pointedly asked if she was committed to pushing Frances’ wheelchair when the time came. Peanut had been too stunned to say the deepest thing she felt in reply, or even to take a swing at Esther. Instead she had said in a puny voice, “yeah,” her eyes cast downward. “Of course.”

“I did go to this place called Debbie does donuts. Spelled D-U-Z,” Frances continued. “I was in my thirties. All the waitresses there were topless, so me and Esther thought it would be fun. But it was this sad boarded-up place and all the women looked really grouchy. We were like a couple of mice ordering our donuts. It was like we were supposed to pretend there weren’t tits in front of our faces.”

“That sums up my whole high school experience,” Peanut said morosely. She tilted her face at different angles before the mirror, assessing each pose. “You know your nose never stops growing. It just gets bigger and bigger your whole life.”

“Sort of the toenails of the face.”

“That’s funny.” Peanut stuck her arm elbow-deep in the paper bag.Tonight we’ll meet, Gram Parsons sang mournfully, at the dark end of the street. You and me. You and me. You and me. They rode past shouting boys on bikes. The sun passed behind a black cloud and one hot spot bled through.

“Do you want any more?” Peanut asked and put the hard edge of a scone into her mouth.

“No. I’m turning the corner toward disgusting.”

“Anyway it really freaks me out,” Peanut said, chewing. “Already my nose is a little witchy and I like that. But in like ten years it’ll be casting the shadow of a small building.”

“I love your nose. You would look all wrong with a small nose.”

“My nose will always be a little closer to you. Like if I kiss you, it gets there first. It’s like a dick.”

The two laughed and were quiet. Peanut resumed her state of contempt almost immediately. She hated herself for being so pleasant, and pledged not to laugh again. We’ll pay for the love that we stole Parson’s cried, and a red-lettered sign whipped by. ARRIVE ALIVE. DON’T TEXT AND DRIVE. The words glowed in Peanut’s mind. She set the greasy paper bag down between her feet in a quiet rage, the effect of which was oddly pretty. Frances looked over admiringly from time to time. Peanut looked her best when she was pissed. She took on the neat poise of a killer.

“Will you wipe off my glasses? It’s like staring through a potato chip.” Frances said and took off her black frames.

The joke was met with incredible disinterest. Peanut snatched the frames from her hand, untucked her t-shirt, and rubbed off the lenses. She handed them back to Frances without a word.

Soon they were riding past squat gray shopping centers, one after another, with slabs of dried grass in between.

“God. Walmart looks like a grocery store in a bad neighborhood,” said Frances.

“America is a bad neighborhood,” Peanut said flatly.

“Do we need anything from there? Maybe we should stop.”

“For what? A seven-foot box of cornflakes. No thanks,” Peanut said with satisfaction.

She leaned back in her seat and repressed a smile.

Frances pulled a dry piece of skin off her lip and a dot of blood rose up in its place. She felt anxious beside Peanut, who sat with her arms folded, resonating anger. Often Peanut veered into dark moods without warning and Frances always knew she was being accused of something, though she rarely knew what. She wanted badly to touch Peanut, but knew she couldn’t. She knew that in Peanut’s stillness, an ambush was coming. “I want to look at you but I can’t take my eyes off the road,” said Frances. “Whatever look you’re giving me, I can feel it.”

“How does it feel?”

“Like standing next to a microwave.”

Peanut sat stiffly, wishing she could somehow prompt an apology from Frances without explaining how she felt. She bided her time like an animal, glancing out the window at fast food signs cast with colored light. She felt sharp and focused whenever she was this angry, and in this way, partly enjoyed the eerie mood between them. Peanut visualized Frances in San Francisco, flirting with whole rooms of women, and then settling on one to lead back to her hotel room. The thought made Peanut sweat profusely. Her legs stuck to the vinyl seat, which had split in three places and been duct- taped. She forced her gaze onto passing discount stores, dark casinos with candy-bright signs. Then a strange smile crept across her face. Peanut tucked her hands under her thighs. “So were you a whore in San Francisco?” she asked in a hostile flirty tone.

“Is that what you want? You sound all turned on.”

“Come on, were you?”

“No. More of a bore than a whore.”

“You didn’t flirt with anyone? I mean out of everyone you met, say you had to pick one—”

“But I don’t have to. You are always demanding that I do this. It’s so demented, Peanut. It’s like you’re baiting me to piss you off. And I’m not going to. I’m not some dog, okay. I’m sorry to disappoint you.”

“I just find it hard to believe. I mean, you can hardly contain yourself at parties. You walk around stroking your tie, waiting for someone to compliment you, and then lean into any woman who shows the slightest —“

Frances shot a glance at Peanut. “Look at you. You’re all flushed. You’re all jealous and turned on.”

“I am not turned on.” Peanut straightened her back. “I’m making a point.” She stared at Frances with a grim determined expression. “So tell me who you found attractive in San Francisco.”

“Oh my god.” Frances sighed. “Okay. Emit I guess.”

Peanut’s eyes grew. “Who’s Emit?” she asked in an oddly cheerful tone that Frances knew could go dark at any moment. Peanut was always playful when gathering information about whomever Frances had paid particular attention to. She felt to Frances like someone holding a dagger behind a curtain.

“Just this drummer I like. He’s a great guy.”

“Well he can get on line.”

“What is that supposed to mean?”

“You think everyone’s great. And you want to have sex with everyone. Men included, apparently.”

Frances opened her mouth to speak but stopped herself. It seemed like a lot of work.

Peanut looked out at crowds of cows in a field. The sun was setting. There was a glare of pink light in the rearview mirror. “What did you want to do to him?” she asked, fascinated.

“Nothing. I don’t know. I was just curious. If I wasn’t with you, I probably would have fooled around with him. He seemed interested too.”

“Did you wish you weren’t with me at that moment?” Peanut asked sternly, panic flashing in her eyes. “I mean, did you fantasize?”

“It’s okay to fantasize. Are you saying you never fantasize?”

“Did you kiss him?”

“No. Not really. I mean, it was a friendly goodbye kiss.”

“Not really? Well it’s a good thing I ask you these questions because otherwise I wouldn’t have a fucking clue.” Peanut looked fiercely at her legs. “You haven’t slept with a man in over twenty years.”

“I didn’t want to sleep with him. It was just a vague sort of animal interest. I’m attracted to men all the time but I don’t want to see what they become in sex.” White headlights whooshed by. “I don’t want to be feminine,” Frances said firmly. “I don’t want to be the counterpart to their virility. I’d wind up feeling like some slain lamb.”

Peanut laughed, surprising both of them.

“I’m not kidding. I remember going to the butcher with my mom as a kid during the spring and seeing this skinned lamb in the window with an Easter lily in its mouth.”

“Jesus.”

“It was the early sixties.”

“I know that.”

Gram Parsons sang his last raspy heartsick song and the two didn’t talk. Frances seemed to be controlling the tense silence between them and this maddened Peanut. She faced the window and cried discreetly, then patted her face with her fist.

Frances felt trapped in the car and wished she were home alone, away from Peanut, her vortex of need. She tunneled into herself and wrote a song. She’s a little biting daisy, tipping into insanity from seventeen directions. Bite. Bite. Bite. Frances strained to commit the words to memory, hating Peanut for having two free hands and not knowing how to drive.

Soon they stopped at an Exxon gas station and went inside in silence, past glaring truckers with fat guts. Peanut bought a giant iced coffee and jalapeno potato chips. She walked back to the car in a huff and began eating the chips without pleasure, sipping coffee between bites.

A tall man tapped on her window. It was open a crack and Peanut could hear him breathing. She looked up and a shrill exhilarated look came across his face. He had a brown handlebar mustache and sunburned nose. Peanut looked away. The man was around Frances’s age, she guessed, though he had aged differently, with his craggy face and distended stomach. He was ugly.

Previously, Peanut had considered people either young or old. If they were young, there were many stages to consider. But after fifty, she had never bothered to gauge one’s exact age. She said Santa. She said old and looked away. After meeting Frances, however, this snide disregard had veered into complete fascination. She fixated on everyone over fifty. She measured gradations of oldness, tracking them on the street. She would see a white-haired man straining to climb a step and want to know how old he was. She would want to ask. To say, “Please sir, I need to know. Because whatever age you say, I’ll file it away and fear that year.” She also felt compelled to know the ages of white-haired people who were walking easily in hip outfits, maybe telling smart jokes. Frances was like that, a swarm of energy. She was attractive in her enthusiasm, which seemed unusual. Most masculine women appeared dour to Peanut, as if they believed that this sort of sulky demeanor was maleness. Peanut was too peevish herself to be near anyone like that.

The man with the brown mustache stared at Peanut for a long moment. He scratched his neck, then walked slowly to his truck. Peanut leaned her head on the cool window glass.

Frances had seen the man approach her car. She stood outside of the gas station with a miserable look of concentration, holding her dim green travel mug and a bag of pretzel sticks. Frances imagined confronting him. Of course he would think she was Peanut’s mother, or maybe her father. Probably he would stare stupidly, trying to decide which. Frances was continually challenged to educate those who oppressed her, to talk openly about her genitals, and because of this she often resisted the urge to confront them at all. Frances found it ludicrous that she be perceived as a parent. She was no kind of parent and never had been. Harrison Ford really is a father, she thought. Possibly even a grandfather, but he will never be called this. In quiet agony, she sipped her coffee and considered man’s eternal separateness from progeny.

Once inside the car, Frances tore open her bag of pretzels and ate several sticks, stealing glances of Peanut, her little foreboding face.

“What did that guy say to you?”

“He didn’t say anything.”

“I saw him. He was standing by the window.” She ate another pretzel.

“He just stared. We didn’t talk.” Peanut said, deliberately aloof. “He had a Bush/Cheney 04 bumper sticker on his truck.”

“It really seemed like he was talking to you.”

“Well, he wasn’t.”

The sun was almost gone and this made them both feel worse. Frances started the car and looked over at Peanut as they peeled out. “You have crumbs all over your shirt,” she said.

“Look at yourself.”

***

In Cumberland they checked into a Best Western hotel, which was run by a bunch of smiling Christians.

“So, two single beds?” the blonde woman behind the counter asked. She wore a hideous white button-down blouse with a pink chest pocket.

“No, one king,” said Frances.

“It’s the same price for two singles,” the woman said firmly, still smiling, determined to believe the two were poor and not perverted.

“One king,” Frances repeated and the woman’s face changed. She was the sort of idiot whose thoughts may as well have boomed from a speaker on her forehead. Peanut and Frances watched her think about them.

The woman stared in amazement. “Alright then,” she said, collecting herself, and tensely typed something into her computer. She put a plastic card on the counter and pointed vaguely. “Up the stairs on your right.”

Frances wanted to smile. This is the great thing about capitalism,she thought. Christians selling queers a bed. Nothing in the world exists but profit.

They dropped their bags off and went across the street to Outback Steakhouse. Peanut ordered a baked potato with sour cream and bacon bits. Frances ordered a full steak dinner. She had always been able to eat heartily under stress and Peanut found this unattractive, too warlike.

Peanut slouched, letting her long brown hair fall over one eye. Lewd tawny light lit the exposed half of her face. “So you’re not going to talk to me?” she asked, pissed to be the first to speak.

“You aren’t saying anything either,” Frances said impassively.

“Well, I don’t know what to say to you when you act like this.”

“What, like mean?”

“More like heartless. Like a piece of statuary.” Peanut stared at Frances. “It’s like you’re autistic.”

Frances smiled like a wolf. “Do you know what that means? To be autistic?”

“Of course I do. Don’t quiz me.”

“Just tell me what you think it means.”

“It means someone who can, you know, rattle off all the prime numbers, but not, like, say hello.”

Frances chewed her steak and swallowed. “I’m like that?”

“Yeah.”

Frances was surprised by how much this hurt her feelings. She continued to eat and wanted to cry.

“I just wish you would speak,” said Peanut. “You could say anything.”

“No,” Frances snapped. She set her fork and knife down. “You want me to say something specific. You want to have a conversation where you write both sides, like a play.”

Peanut looked at her potato and wanted to shriek. It was true that she often staged conversations with the hope of eliciting particular responses from Frances, but for this she felt no remorse. It seemed to Peanut that Frances didn’t know how to talk to people. She could be unduly frank, accidentally mean. She needed help.

***

On the table in their hotel room there were cheap butter cookies in a plastic wrapper. Beside them a card read, To Our Guests: Because this hotel is a human institution to serve people, and not solely a money making organization, we hope that the peace of Jesus Christ will rest on you while you are under our roof.

“You believe this shit,” Frances muttered. On the card she wrote,this is actually really offensive to Jews and Muslims, then sat in a maroon chair and ate both cookies.

Peanut was too tired to maintain her cold exterior. She turned on the television and took off all her clothes, then poured herself stomach-down into bed.

Frances apologized from the maroon chair, though she still didn’t know entirely what for. She walked to the bed and stood there.

White sheets covered Peanut’s ass and legs. Blue TV light blinked on her back. She peered over one shoulder to see Frances’ expression and then put her face back on the pillow.

Frances sat on the edge of the bed and stroked her head and back carefully, as if she were touching a terminally ill animal. Peanut’s mouth fell open. She let out a little groan, loving to be touched this way, like she was sick and precious. She cried in a small way that soon opened into a breathy sob.

Peanut was flipped over and explored. She continued to cry and it felt fantastic. Between gasps she explained that the last few hours had been lonely. “And you should have called me back in San Francisco.”

Frances nodded sincerely. She was moved to see Peanut cry.

Peanut wiped her face with her fist and sat up, relieved enough to notice how uncomfortable she was. “I hate a tucked sheet,” she said and began tugging the sheets loose.

“I like it tucked.”

“I like one leg out.”

“Well, you’ll like menopause, then. That’s all it is. One leg out all the time.”

***

Later the two lay naked in bed, idly touching each other’s bodies, lights out.

“You sound like you’re crying when you cum,” said Peanut.

“That’s so embarrassing.”

“No, I like it. It actually sounds somewhere between crying and laughing.”

“You sound like a puppy being rolled off a cliff.”

“No, I don’t,” Peanut laughed.

“You do. And your back tenses. It has this great indent like an ass or a peach. A long peach.” Frances held Peanut’s jaw. “Please spend the rest of my life with me.”

“You mean our life. Spend the rest of our lives together.”

“No, my life. I mean, yours will go on after mine,” she said in an oddly casual way, as if she was talking about someone else’s death.

“You don’t know that,” Peanut said and a restrained sob entered her voice. “I mean, there’s no way of knowing that.”

“It’s easy to assume.”

“I could become very sick. Maybe I’m sick right now and it’s invisible for the moment.”

“I bet you aren’t.”

“Or what about that volcano? It could cause a global holocaust.” Peanut took a breath. “I think about you dying all the time and it feels so stupid. I mean, I’m basically stunned the world isn’t over. It could end any day. So why, you know, dwell on any moment beyond this one?” She made the monstrous near smile of someone about to cry, and then squashed the expression on Frances’ shoulder. Peanut stayed there for a moment and then withdrew her face with a great breath. “When people make plans to, you know, meet someone their own age and get married and have a baby and then, I don’t know, have some synchronized death, it just seems like this denial of what we know to be true about life. That it ends. And we can never know when.”

“So you never wish I was younger?”

Peanut was startled by this question. “No,” She insisted, putting her hand on Frances’ flat chest. “I’m in love with you now. But sometimes I want to meet the other yous. Like, I want to hang out with you in 1970. I want to meet her.”

“I love you from 1970. I love you from all points in my life,” Frances said, moving her knuckles over Peanut’s stomach. She wanted to stay awake forever, to never let go. Frances hated the vulnerable moment before sleep. She felt she might drop right into death.

Peanut sat up, moonlight from the window pouring on her face and shoulders. She stroked the backs of Frances’ legs, saying “darling” again and again, all the while dwelling on thoughts of a world without her darling. It was hideous to contemplate.

Peanut thought about time travel. How could she not? She thought about wormholes and machines from science fiction movies, all the magic that could save them. If only time were stretchy, she thought, then her sense of time could be speeded up and Frances’s could be slowed down. She felt embarrassed thinking this way, but also entitled. Because everyone else had it wrong. The problem with their relationship wasn’t moral at all. It was biological. It came down to the bodies they happened to have and the looming fact of death.

In the morning Frances woke up before Peanut. She got dressed and brushed her teeth and stood before the bathroom mirror staring at her face. The white overhead light was bad and she found her appearance a shock. Frances didn’t feel like the person she saw. She didn’t feel old. She had always identified herself with her body’s powers and saw that they were slipping away. So who was this other person? Frances considered the assembly line of existence and the one thought looped in her mind. I’ll die too?

Peanut walked in naked and sat on the toilet to pee.

“I look like some rotting Keith Richards,” Frances said.

“You are so vain.”

“I know.” Frances poured oil from a skinny brown bottle into one hand and worked it through her hair. “You know what the worst thing about aging is?”

“You’re always telling me what the worst thing about aging is. I’ve heard like sixty worst things.”

“Well, in the moment it always seems like the worst thing.”

“Okay, so tell me.”

“Eyebrows. I keep looking at pictures of myself and thinking what’s wrong with my face? Oh, I have no eyebrows. And there’s nothing to be done! You know, straight women start to pencil them in but that looks really freakish.”

Peanut flushed and stood up. “I have this weird dark hair on my stomach.” She pointed to her abdomen. “I pluck it and it grows back.”

“Well I have, like, an eight-foot whisker coming out of my neck.”

Peanut walked over to Frances, examining her. “It’s barely noticeable. And anyway that’s normal. It’s an aging thing. But I shouldn’t have stomach hairs.”

“Well, you know, your friends have probably already told you this, but it’s contagious.”

Peanut smiled and kissed Frances’ ear. “Darling, you’re completely hot,” she said and hugged her from behind, clasping both hands over her chest. “I chased you, remember?” she said. “You didn’t even like me.”

Frances grinned. “It wasn’t that I didn’t like you. I just thought you were so young. I mean, you seemed like an absurd candidate for my love.”

Peanut knelt on the floor and turned Frances toward her. She kissed her knees, then held them like apples and looked up triumphantly.

Frances laid her hand on Peanut’s warm head. “Baby you’re such a dirty opportunist.”

***

After checking out, Peanut and Frances had their photo taken by an unfriendly man in the parking lot. It turned out he was just European, which they later laughed about. He took five pictures, each at the wrong moment.

“I look increasingly like a leprechaun,” Frances reflected as they scrolled through the pictures on her digital camera.

“Well, I look pale and crazy. Like I’ve just been let out of an institution for a little sunlight.

The last photo was the worst. They exploded into a fit of laughter.

“Jesus. I look like some gnomish version of Iggy Pop!” Frances cried.

“You do! And look at me. I love how deliriously happy we look. Like we have no idea how ugly we are.”

***

They drove up dirt roads, passed dilapidated farmhouses with brown chickens patrolling out front. As directed by Gail, Frances stopped at the last green shed and parked under a tree.

They began walking and approached a dark barn with a beaming tin roof. Rusted farming implements lay sunken in the earth out front. Peanut pointed to a group of black-spotted pigs, lounging in the sun with drunken looks. She put her hand over the chicken wire and they came running, leaning their genital-soft snouts to her fingers. “Pigs are very smart,” Peanut said, stroking one on the face. “Smarter than dogs. And toddlers.”

Frances stared at the pigs. “Maybe we could have one someday. And a horse,” she said. “Life doesn’t seem long enough.”

“It isn’t,” Peanut smiled.

They walked on, past staring goats. Over raised roots, green weeds shooting up around rocks. The two stopped at a dented aluminum mailbox on a wood post. They walked up the gravel drive and through a high metal gate.

Barking dogs came bounding toward them. Gail stood from a plastic chair on the porch, waving. She wore a collared peach dress with square front pockets and a dirty beige visor. A barking spaniel leapt at her feet, nipping the hem of her dress. “Gladys!” she said sharply. “Cool your jets.”

Peanut spotted Tony immediately among the pack, trotting their way. A bright fox with dark wet Disney eyes, pink tongue out.

Gail shook hands with them. She looked wind-beaten and suspicious. Frances recognized her hands from the photograph on petfinder.com.

Tony began rolling on the grass and Peanut knelt, following him with her hand. He laid submissively for a moment, accepting a stroke, the sun in his orange hair. Then the dog stood on his skinny hind legs and licked her fingers ecstatically.

Gail stared at them. A wide grin spread across her face. “He’s cuter than in pictures, huh,” she said. He was. Peanut rubbed his rabbit-soft chest in awe, his heart beating so closely to the surface.

Gail warned that Tony would cry for a few days and they nodded, their eyes fixed on the animal. “I like pictures,” Gail said. “Send pictures of him.” She handed Peanut a record of Tony’s vaccines and a zip-lock bag full of brown kibble, then a little blue harness and leash.

Peanut gave Gail a check and lifted the puppy up into her arms. “Oh my god,” she said, beaming. It was the gentlest weight, like a small bag of flour. Frances stroked the dog’s face with one finger. “I know.”

In the car Peanut held the dog with both hands and wanted to write. Black birds flitted by and she let herself forget the poem growing in her mind, which felt wonderfully wasteful, almost decadent. What kind of radio is a bird? How do they know where to go? Peanut grasped the dog in a tranquil daze.

“You look like you just gave birth,” said Frances.

“I feel like I did.”

Frances glanced at Tony. “He seems like a serious little guy.”

“He does.”

“What fine career could he have where no one would notice he was a dog?”

“Shrink?”

They laughed and laughed.

“He could have an assistant explain all of his intentions,” said Frances.

“He wants you to take him for a walk,” Peanut joked.

***

They passed long low humps of grass, gray trucks like a train of elephants. And a green sign that said Historic Tree Nurseries, Exit 41, with no explanation. Both thought of what this might mean. Peanut pictured people kneeling to water rows of tiny baby trees. Frances thought of dioramas of people planting trees in the past. The dog began to cry. It sounded like he was being burned with cigarettes. Then he rolled onto his back and looked up distrustfully, his bright white chest thrust forward like Christ. “Chihuahua on a cross,” Peanut cooed in a mockingly piteous voice.

“That sounds like a band name.”

“We should claim to be in that band. Like when people think you’re my mom, we should say no, we’re band mates.”

“That’s so great.” Frances cocked her head in thought. “Because I really hate making a point of saying you’re my girlfriend. People always wind up looking ugly when they try to make a point.” She took one hand off the wheel to touch Peanut’s leg. “Our first album could be called ‘Frantic Licks’.”

Peanut roared with laughter. “You know darling, you look a little like a dog. Because you are kind of always smiling. And you smell like a dog. In a good way.”

“I think I was a dog.”

“No you are a dog.” Peanut looked out at the wide road, the white light beaming on car tops. She patted Tony. “You don’t really believe in reincarnation do you?”

“Well, not really but it’s very appealing. I sort of entertain it, with past lives and stuff. Like, my mind slips into it metaphorically. You never think about having other lives?”

“No.”

“So you think people die and then just return to static.”

“No, they return to nothing.”

***

They passed lush green farms, black cows in profile on the crest of a hill, a dead deer arranged with its bottom facing the road. Tony’s cries were reduced to a croaking whimper and then in grim acceptance, he tucked his snout between Peanut’s knees.

They weren’t at all hungry but figured they should eat. Frances took the next exit and pulled over. They sat on a skinny plot of grass in the shadow of a taco chain. Tony peed reluctantly, tugging at his leash.

Frances bought nachos and they ate cross-legged on the grass, holding the cardboard boats up in front of their mouths, away from Tony.

“He has the build of a piglet,” said Frances.

“A pig in a fox costume.”

“A very clever pig who didn’t want to die.”

The dog stood on his back legs with a desperate expression, begging for all the things he smelled. “Look at him,” Peanut said, smiling.

“Dogs are so more apparently animal than us that we get to laugh at their desires,” Frances declared. Peanut agreed. They wiped their mouths and held each other. They looked down at the dog, their tiny witness. He laid stomach-up in the grass.

Frances stroked his throat. It occurred to her that she could die around the same time he did. The thought was a shock and then felt sort of funny. She smiled at the animal, the little measure of his life.A nano life that matches the end of me, she thought.

Frances put her hand on Peanut’s shin. They both looked down at the hand and then, sensing that people were staring, Frances withdrew it and looked up.

They were surrounded by teenagers with benign captivated expressions. Wives grabbed their husbands by the arm, pointing gleefully. A little boy stepped forward and shyly asked to pet the dog.

Never before had the two been so tenderly observed. They looked at each other and then back at their audience, alarmed. Strangers stood patiently, all lit up, beside a single gnarly tree. Tony tilted his head, ears erect. He studied the crowd and they crept forward. Everyone wanted to touch him. Everyone beamingly asked, “What kind of dog is that?” instead of “What the fuck are you?”

When people left, new strangers appeared. Some stood at an arm’s length and they were radiant, waiting for their pleasure. They seemed to be touching the dog even before their hands had landed. Tony offered his underside and stared up seductively. He had an appetite for everyone. The dog was littleness itself and this was his power. People weighed him in their hands. They pointed out his smallness repeatedly, almost to the point of chanting, as if Peanut and Frances were in denial of the dog’s size and needed to be convinced. “He’s a tiny baby!” a young girl blurted.

This is what it means, Peanut and Frances realized, to be the keepers of something beautiful. This is what it means to become other people. They thought about what they had been when they stood next to each other. Freaks, strutting their base interests. But now, next to the dog, they lost their queerness, if only for a moment. “We’re sort of like Elvis’s family,” Frances whispered. “The trash these people are willing to put up with to get to the king.” Tony shot them a long look, as if in agreement, and stepped out into an area of sunlight. He was more aware of his beauty than any creature they had ever met. Everyone crawled around him. They sat in the sun, fondling his warm velvet head. And he shined.